LA Living

Life for Los Angeles residents is neither as dreamy nor as cynically corrupt as presented in many films. The nuances of real lived experiences in Los Angeles include both challenges and triumphs, as individuals and communities find opportunities while also facing down oppressive systemic forces. The benefits of economic improvements in a neighborhood are not always shared equally, as gentrification often forces communities to relocate. Still, communities are not entirely without agency, and people increasingly have the ability to control their own narratives through alternate media. In Hollywood's attempts to reconcile reality with film magic when depicting slices of "real" Los Angeles, it quickly becomes clear how difficult it is to accurately capture "reality" in a dynamic urban space.

Boyz n the Hood (1991)

Boyz n the Hood follows Tre Styles and his neighborhood friends growing up in South Los Angeles. Styles' friends, Ricky and Doughboy, are brothers. Doughboy is arrested for stealing early in the film, and at his release party, it becomes clear it was not his first arrest. In contrast, his brother Ricky stays out of trouble. Boyz n the Hood encapsulates the neighborhood's dynamics in the early 1990s. Outsiders saw South Los Angeles as a place rife with gang violence, but there was also an incursion of outsiders trying to buy up the land, take resources, and push the community out. Younger community members' parents and friends pressured them to leave, partly because the neighborhood was unsafe, but also because of an impression that the outside world was better than the "hood." The depiction of the neighborhood as solely a bad place overlooks the complexities of neighborhood dynamics, broader systemic issues, and the work and agency of the community.

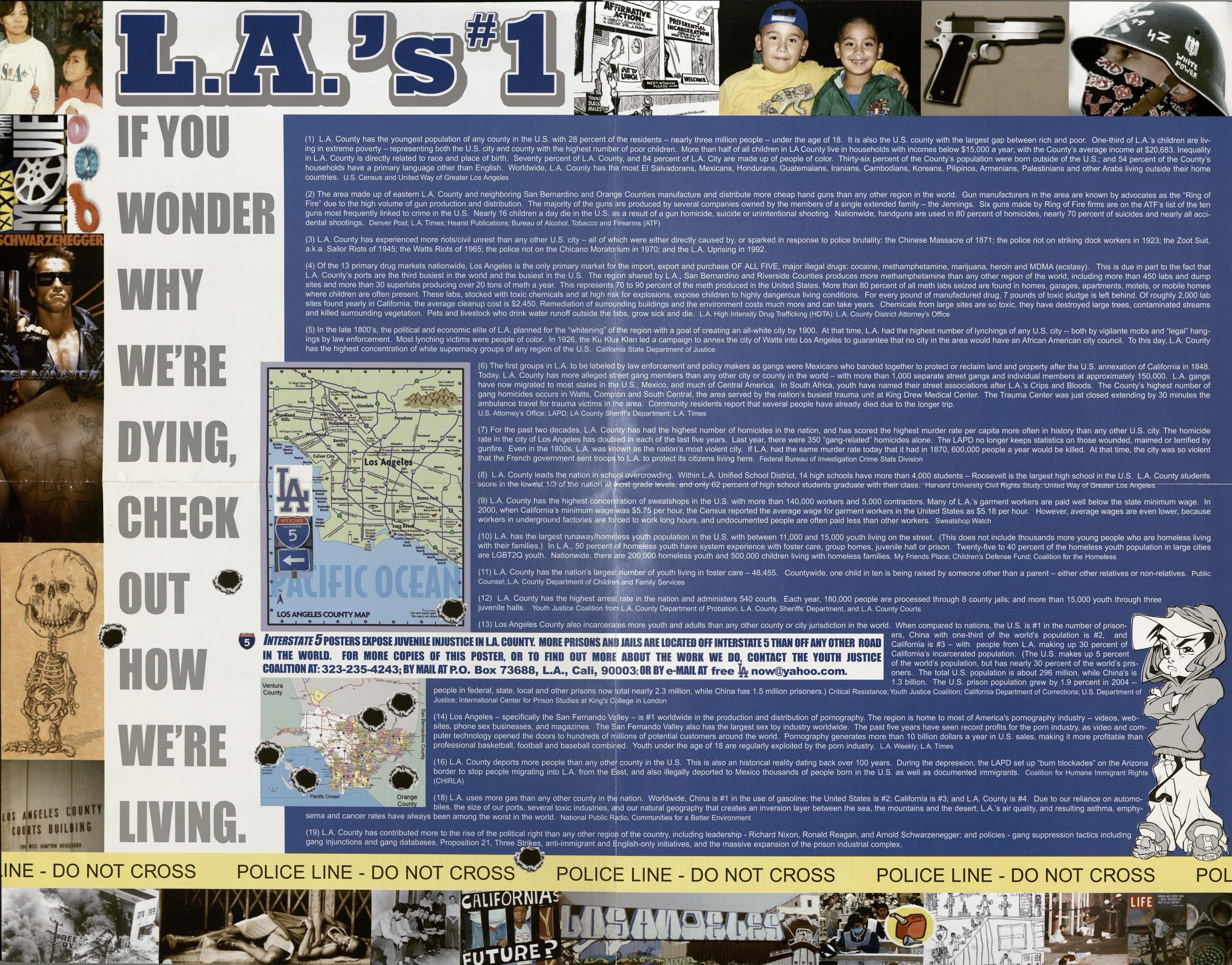

How We're Living

The League of Women Voters of Los Angeles used this poster to explain the many reasons why the greater Los Angeles community and its systems continued to fail communities in need. Some of the points are reminiscent of Styles' father's remarks in the film about the negative impacts of gentrification on their neighborhood and the removal of money from their community. When an elder challenges him, blaming the people in the community by saying "it's these guys killing themselves," Styles' father quickly responds with a rebuttal. He believes outsiders who infiltrated their community are the reason guns, drugs, and other things kill so many. Both the film and poster point out systemic problems in and around Los Angeles that individuals and communities continue to battle.

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

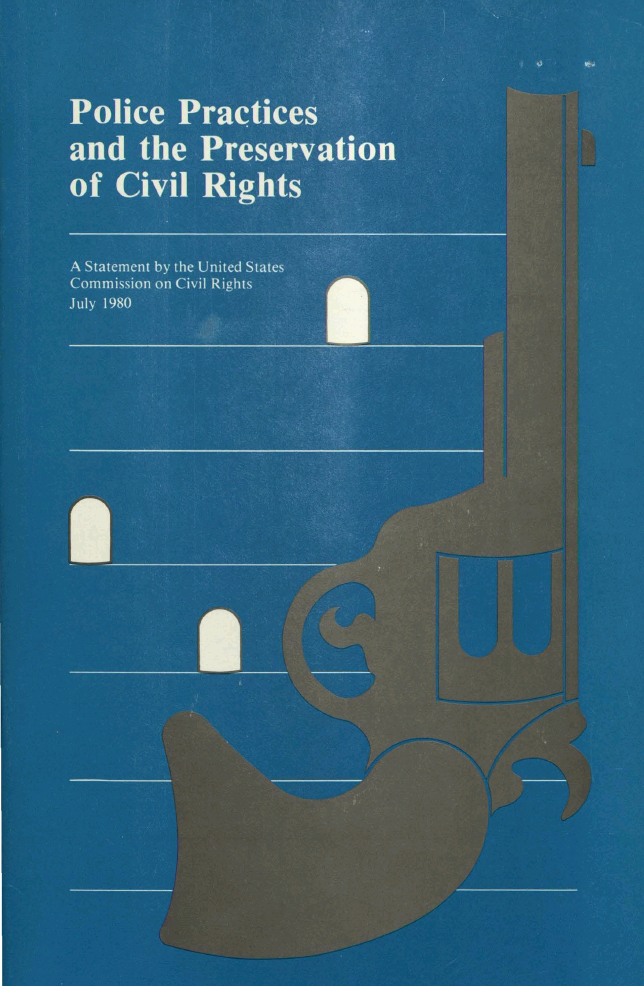

Police and Civil Rights

The United States Commission on Civil Rights created this booklet in response to police brutality during civil uprisings in Florida in 1980. After the acquittal of the police officer who brutally murdered an innocent man in Florida, there was a consensus that police activities should meet the standards outlined in this booklet. In Boyz n the Hood, Tre Styles has an encounter with two police officers, one black and one white. The Black officer, who used verbal aggression during an earlier encounter with his father, used physical force and aggression toward Tre. As a member of an overly-policed community, he understood the potential repercussions of fighting back against the officer, and felt he had to take the abuse to preserve his life. The film was created a decade after the booklet and shows that the standards presented by the Commission in 1980 did not result in significant change. Police brutality continues to be an issue in Los Angeles and other cities across the U.S.

View Document (PDF)

Non-Violence Training

This interview features members of the California Association for the Education of Young Children involved in creating their Non-Violence Training Program. Boyz n the Hood depicts violence in Styles' South Los Angeles neighborhood, including the ways young children experienced it, even if they were not directly involved. In particular, children in the film hear and see death in their community, which affects them deeply at home and at school. In one scene, we see Styles at school and glimpse classroom walls decorated with children's drawings of helicopters, police cars, and violent acts. The California Association for the Education of Young Children Non-Violence Training Program intended to assist children and help them cope with the violence they experienced.

Falling Down (1993)

Falling Down stars Michael Douglas as William "D-Fens" Foster, a seemingly average white man recently laid off from his white-collar job. Foster abandons his car in stopped freeway traffic, in favor of walking from downtown Los Angeles to Venice to attend his daughter's birthday party, despite a restraining order taken out against him by his ex-wife. As he traverses the city, he channels his rage into violence in an attempt to control the situations he finds himself in. The film perpetuates many stereotypes as he passes through diverse Los Angeles neighborhoods, most notably its portrayal of a Korean-American grocer who over-charges for groceries, men in gang clothing demanding a toll to sit on a hill, and a racist-misogynist-homophobic owner of a military surplus store. D-Fens's journey across this multilayered city challenges his assumption that society will see him as virtuous by default, as he mutters bewilderedly, "I'm the bad guy?...How did that happen?"

Community Relations

In the 1980s and 1990s, tensions between the Black and Korean-American communities in Los Angeles sometimes flared into violence. This article notes a violent encounter between a Korean-American market owner and a 14-year-old Black girl that occurred less than a year before storeowner Soon Ja Du shot and killed 15-year-old Latasha Harlins over a misunderstanding about payment for orange juice. This event, along with continued tensions between the two communities, are considered contributing factors in the targeting of Koreatown during the 1992 Los Angeles uprising. Despite the tensions flaring up in corner stores due to a lack of understanding, as this article notes, individuals in the Korean and Black communities were actively trying to bridge the gap by opening up dialogues with one another. In Falling Down, when D-Fens asks for change at a corner store, the owner asks him to purchase something to get change. In this short interaction, D-Fens becomes aggravated and begins vandalizing the store after a tirade about the prices being too high.

View Full Article (PDF)

Urban Stress Test

This stress test was created by Zero Population Growth in reaction to "unprecedented growth affecting the quality of life in our cities." It shows environmental and other stressors for each city in the United States, and then ranks them from the least to most stressed city. They considered things like large population changes, overcrowding, high crime rates, unemployment, and environmental factors. Los Angeles, rated as one of the most stressful cities to live in, is in "The Losers" column. The Stress Test states that metropolitan areas had a tendency of being much more stressful places than rural locations. In Falling Down D-Fens is constantly triggered by the challenges of his urban surroundings, beginning with the film's opening scenes.

View Full Program (PDF)

History of Forgetting

The 1992 Los Angeles uprising, spurred by the acquittal of police officers who beat Rodney King, interrupted the filming of Falling Down. The History of Forgetting discusses how the film portrayed Los Angeles at this time, and how audiences received the portrayal. Some enjoyed D-Fens' reactions against all of the "bad" parts of the city, and viewed his character as a type of anti-hero defender of Los Angeles. Others reacted with horror at the film's many misrepresentations of the city, portrayed as if filled by horrible people and entities waiting to take advantage of innocent white men. Falling Down heightened the drama of the city's challenges without overtly acknowledging the complex issues faced by Angelenos.

Training Day (2001)

Training Day follows a single day in which a young Los Angeles police officer, Jake, is evaluated by a corrupt senior officer, Alonzo. Needing to get $1 million to the Russian mafia by the end of the day, Alonzo makes plans for robbery and murder with other corrupt cops in the department. Though technically not based on the Los Angeles Police Department Rampart scandal (1998-2002), the original screenplay offers significant parallels, and the movie was filmed in and around the Rampart district to add realism. The Rampart scandal implicated over seventy police officers for misconduct in the Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums (CRASH) anti-gang unit. Before cell phones provided a preponderance of American citizens with the ability to capture video almost anywhere, images of police and police corruption were often limited to fictionalizations produced by Hollywood. Since television and film, seen by tens of millions of people around the world, were the only visual records widely available to the public, these media possessed an unequivocal and unbalanced authority in their ability to develop public opinion and collective memory on the subject.

Realities of L.A.: Police Corruption in Training Day and Characters' Symbolism

Realities of L.A.: Police Corruption in Training Day and Characters' Symbolism (Audio transcript )

Consent Decree

Following the Rampart scandal, the U.S. Department of Justice and the City of Los Angeles negotiated a consent decree, a legally binding agreement between the federal government and our local law enforcement agencies. District Judge Gary Feess approved and signed the decree in June 2001. Initially set for a period of five years, Feess extended the decree, finally lifting it in 2013. This document provides context to the decree, including background on how it came to be, a very brief overview of areas it covered, and some of its provisions, including administrative staffing and budget, duration, training, systems of reporting, and an early warning system for high-risk behavior among officers called TEAMSII (Training Evaluation and Management System, second generation). The consent decree was created as a direct result of corruption like that depicted in the film.

View Additional Pages (PDF)

Consent Decree Fairness Act

Senator Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and Representative Roy Blunt (R-MO) introduced the Federal Consent Decree Act (S.489/H.R.1229) in 2005. Its purpose was to limit the duration of federal consent decrees to four years and/or the election of new state or local officials. As stated in this opposition letter, the bill, if passed, would require a fundamental shift in the burden of proof. In these cases, it would be guilty until proven innocent and would give "defendants ... a new incentive to 'run out the clock.'" The Act, which did not pass, would have reduced the appeal and effectiveness of consent decrees as a component in policing reform and accountability efforts.

View Document (PDF)

Frank del Olmo Notebook

Following the Rampart scandal within LAPD, newly elected Mayor James Hahn refused to support Police Chief Bernard Parks for reappointment, and in April 2002 the Los Angeles Police Commission voted 4-1 against his reappointment. Shortly after, Los Angeles Times reporter Frank del Olmo spoke with Chief Parks regarding his retention review. Parks had some harsh words for the Police Commission. Quotes in del Olmo's notebook include, "The system was corrupt from the beginning." "The [Police] Commission refused open hearings." "They [the Police Commission] had the City Attorney, I wasn’t allowed an attorney."

View Notebook (PDF)

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

Real Women Have Curves (2002)

Real Women Have Curves illustrates the challenges of navigating between differing cultures in a city composed of layers of diverse communities. It is a coming of age story about Ana, a Mexican-American teen navigating life at her Beverly Hills High School and life with her family in East Los Angeles. The summer immediately after graduating, she contemplates and considers her family's expectation that she go to work in her sister Estela's shop, as well as her personal dreams and aspirations to attend college. Throughout the film, she struggles to make decisions as she works to balance competing priorities while engaging with issues of labor rights, small business ownership, and the value of education for both children and parents.

Women in Business

This KCBB news report follows several women who opened or expanded their businesses in Los Angeles with the assistance of the Coalition for Women's Economic Development (CWED). In the film, Ana's older sister Estela owns her own garment business. When Ana is told to work in her sister's garment factory, she is appalled to learn how little her sister receives for dresses that are resold at an extravagant price in stores like Bloomingdale's. Estela struggles to manage dress production and pay the factory's bills. In Los Angeles, the Coalition for Women's Economic Development is a great example of how a "microenterprise development organization" assisted women in Estela's situation.

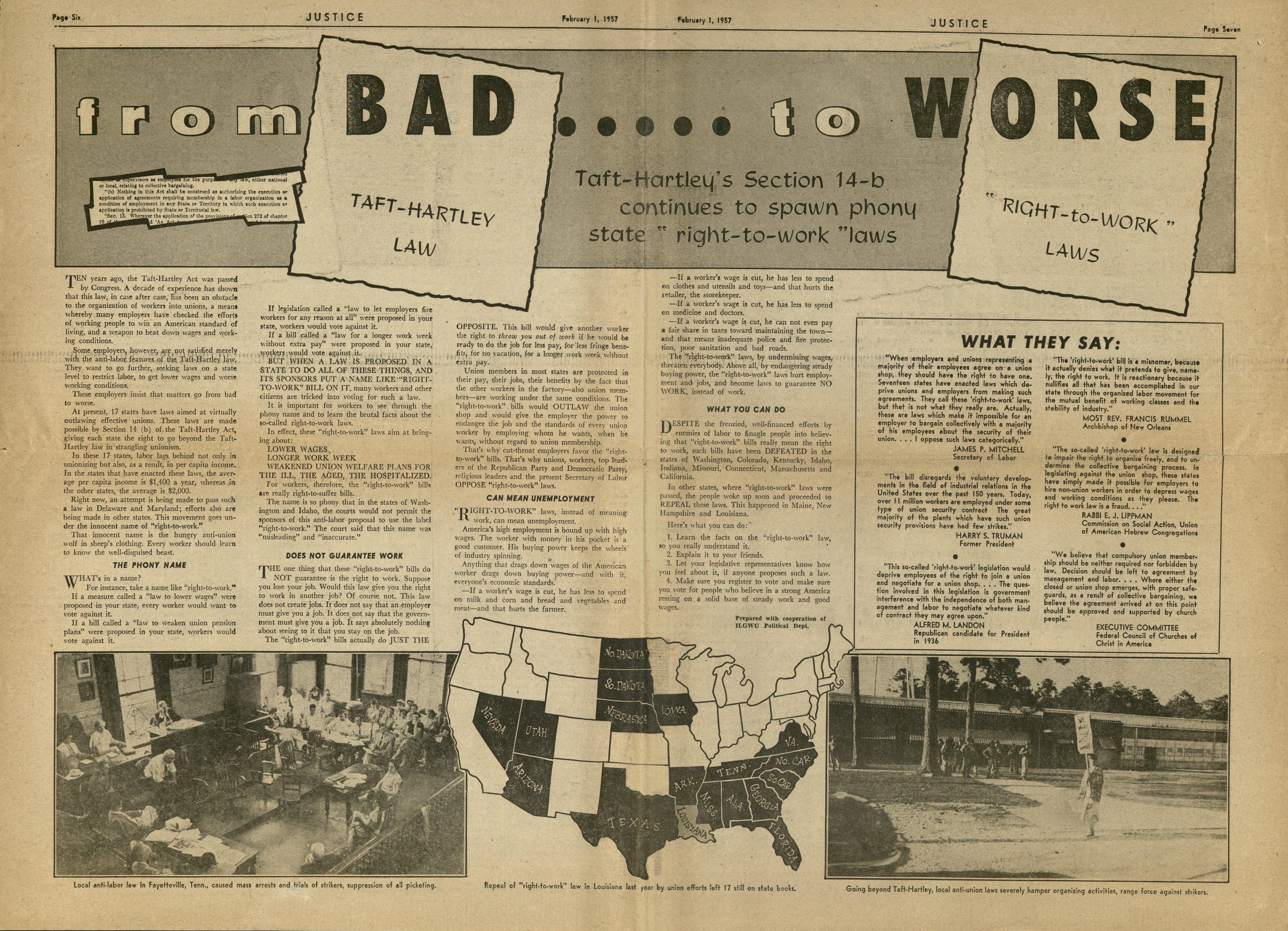

Right-to-Work Law

This 1957 union newspaper is evidence of a push for wage increases and improved working conditions. It discusses the "Right-to-Work Law" then being considered, and how, if passed, garment employees would not benefit. Although California is not clearly on the map shown, the article mentions that this law was "DEFEATED" in the state. In Real Women Have Curves, the garment industry's standards are not far from what was described in the 1950s. In Estela's shop, high demands on a minimal staff, the heat of the shop, and a relentless pace challenges workers. Early in the film, Ana mentions a continued fight about wages and working conditions. There was no union in Estela's shop, but there is a clear disconnect between the high retail prices of the garment pieces the workers make, and the low pay workers received.

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

Child Development

This video clip from the Child Development Facility Accreditation Project highlights the importance for young students to experience culture and language immersion programs in a classroom setting. In the film, Ana's teacher and mentor Mr. Guzman encouraged her to apply to Columbia University. Ana was interested in pursuing an education, but was hesitant because of her obligations to her family and the importance of working in the family business. When Mr. Guzman arrived at Ana's house and asked about her college application, he tried to communicate with her parents, but they had already made up their minds about her future. Both the film and California accreditation programs developed in the early 2000s demonstrate the importance of strong rapport, communications, and cultural empathy between students, parents, and teachers.

Walkout (2006)

Walkout focuses on the 1968 student walkouts of Chicano students at seven East Los Angeles high schools, which led many students to question authority and organize themselves. First, they try methods like surveys to get the attention of administrators and the school board. When that fails, the students move forward with more disruptive methods. With help from college student organization UMAS (United Mexican American Students) and teacher Sal Castro, students organize a series of choreographed walkouts. Their stated goals were educational reform on issues like dropout rates, overcrowded classrooms, low test scores, understaffing, and Chicano representation in the curriculum. Students also desired the cessation of institutional racism in Los Angeles Public Schools, examples of which included corporal punishment for speaking Spanish in school. Walkout is a glimpse into a Los Angeles distant from Hollywood and reminds viewers that Los Angeles is not a land of opportunity for all by default.

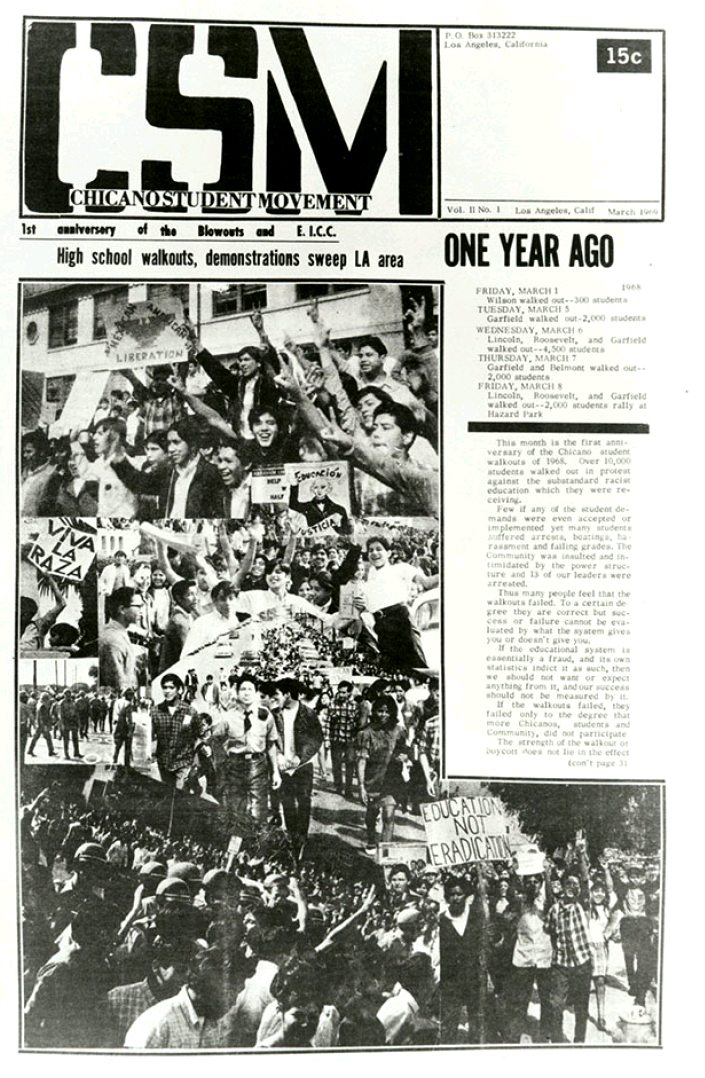

Chicano Student Movement

The cover of the March 1969 issue of Chicano Student Movement highlights the first anniversary of the 1968 student walkouts. It contains several images of the walkouts, as well as a timeline listing the number of students that walked out at specific schools over several days in March. The accompanying article notes the risks the students took walking out, as many suffered "arrests, beatings, harassment, and failing grades." It attempts to discern the success or failure of the walkouts, while also noting that "success or failure cannot be evaluated by what the system gives you or doesn't give you."

View Document (PDF)

Walkouts Retrospective

In March 1978, a decade after the 1968 East LA Student Walkouts, the Los Angeles Times published this retrospective of the event, written by Chicano reporter Frank del Olmo, a CSUN alum. While the first-anniversary cover story laid out some of the issues and challenged the success of the walkouts, this article ten years after the event takes a longer view of the resulting incremental changes. It also allows some of the student leaders to reflect on the past with the benefit of ten years’ hindsight. It describes a decrease in dropout rates, an increase in college-bound students, and an acceleration of changes instigated before the walkouts as positive results. While viewpoints are not entirely uniform, most interviewees aligned their views with the title of the article, "No Regrets."

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

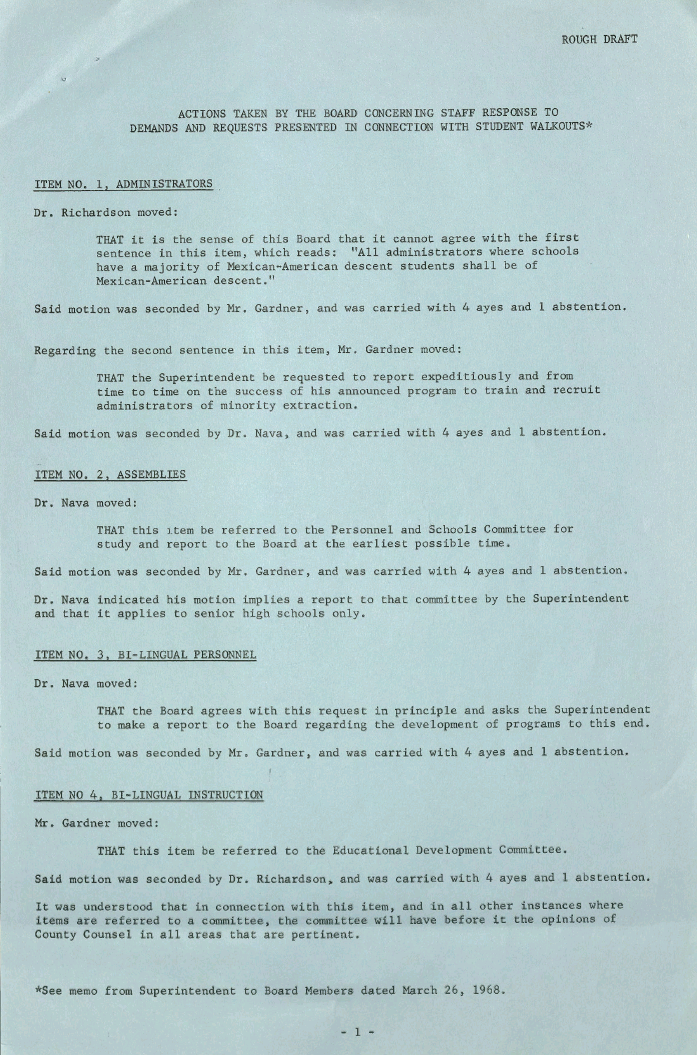

Board of Education Response

After student activists presented a series of proposed reforms during the 1968 Student Walkouts, both Los Angeles Unified School District faculty and the Board of Education responded. This three-page document is the Board of Education's response to the first 15 of 36 items presented by the students. It provides a very brief comment referring to each student demand, a motion with the name of the Board member that proposed and seconded it, and the outcome of the Board’s vote. While reform can be difficult to see in real time, this document indicates that student demands were taken seriously by the Board of Education, which acted upon them with some urgency.

View Full Document (PDF)

(500) Days of Summer (2009)

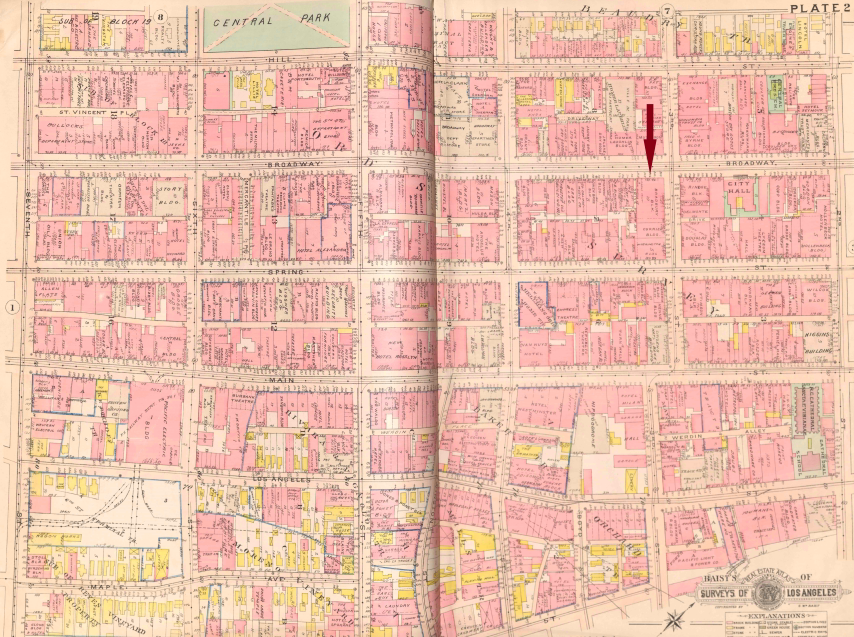

(500) Days of Summer is a romantic comedy that follows aspiring architect Tom and his love interest Summer as they work and live in downtown Los Angeles. As they walk around downtown on a date, Tom urges Summer to look up at the tops of the high rise buildings and appreciate the intricate architectural details in the Historic Core. He also takes her to his favorite park bench with a sweeping view of the city only slightly marred by ugly parking structures. The heart of Los Angeles' shopping and theatre scene in the early 20th century, downtown Los Angeles transitioned to a central place of entertainment for the Spanish speaking community, and in more recent years has been significantly impacted by gentrification and changing demographics. Although he laments the new parking lots, Tom, an affluent white Angeleno, is himself part of a wave of change to the downtown area. (500) Days of Summer romanticizes the revitalized downtown aesthetic, while often overlooking people who lived and worked there before recent efforts at gentrification.

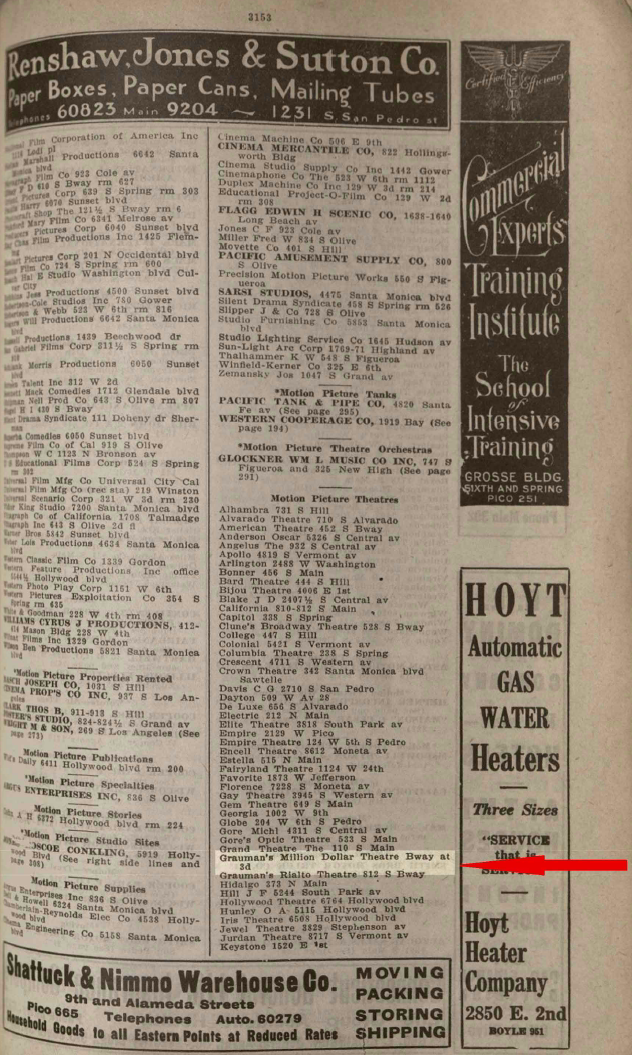

Million Dollar Theatre

The Million Dollar Theatre, originally known as the Grauman's Million Dollar Theatre, was Los Angeles' first lavishly decorated movie palace. When it initially opened in 1918, it lured upper class Angelenos to the movies. Patronage changed after World War II when investment in downtown neighborhoods declined and suburban sprawl and freeways proliferated, drawing residents and film fans away from the city center. Starting in 1949, the Theatre became the venue for many Spanish language films and vaudeville shows, and continued in this role well into the 1980s. In (500) Days of Summer, the Theatre stands in for a revival movie house where Tom and Summer watch The Graduate. Throughout downtown Los Angeles' changes, the Million Dollar Theatre has transitioned along with the needs of the community.

View Full Document (PDF)

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

Bradbury Building

The Bradbury building is one of the most well-known buildings in downtown Los Angeles, and is used as a location in many films. Originally built in 1893, it is now the oldest commercial building in the city's center. It sits across the street from Grand Central Market and down the street from Angels Flight, two other revitalized and historic downtown locations. In (500) Days of Summer, Tom lives near the Bradbury building where he meets a new love interest and interviews for a new job. In this film, the iconic building is the site of new beginnings. Los Angeles is frequently viewed as a place where the old is replaced by the new, but this 2009 view of Los Angeles values and celebrates the historic built environment. Alongside million dollar developments turning old office buildings into lofts, this building is evidence of the enduring value of Los Angeles' historic buildings.

View Full Document (PDF)