LA Critique

While Los Angeles is often portrayed in film as a beacon of hope, the city's highlights can also cast shadows that hide dark truths. Some film genres, like film noir, often present what initially seem like appealing aspects of life in Los Angeles as deceptive. Noir and other genre films set in Los Angeles often position the city as a site of cynical critique. The protagonists in these films often operate from outside established societal systems, and question things the mainstream takes for granted or sees as positive. What is the cost of achieving the Los Angeles dream, and what does it mean if the dream is fraudulent?

Double Indemnity (1944)

Released in 1944, Double Indemnity is set in the pre-World War II world of 1938. The film opens with Pacific All Risk Insurance salesman Walter Neff visiting the Dietrichson home in Los Feliz to sell him a renewal on his expired auto policy. Neff knocks on the door of "one of those California Spanish houses everyone was nuts about 10 or 15 years ago," and is greeted by Phyllis Dietrichson. She charms Neff into a murder plot centered on a premeditated "accidental" death that would trigger their insurance policy's double indemnity clause, thus doubling the payout. While the Los Angeles sunshine abounds outdoors, the suburban interior is a place of darkness, as the 1920s optimism of the home's construction has become a dead-end present. Double Indemnity is a noir film steeped in cynicism, portraying a sunny, picturesque Los Angeles suburb as a beautiful setting for murder.

Double Indemnity as a Moralistic Critique of Los Angeles

Double Indemnity as a Moralistic Critique of Los Angeles (Audio transcript )

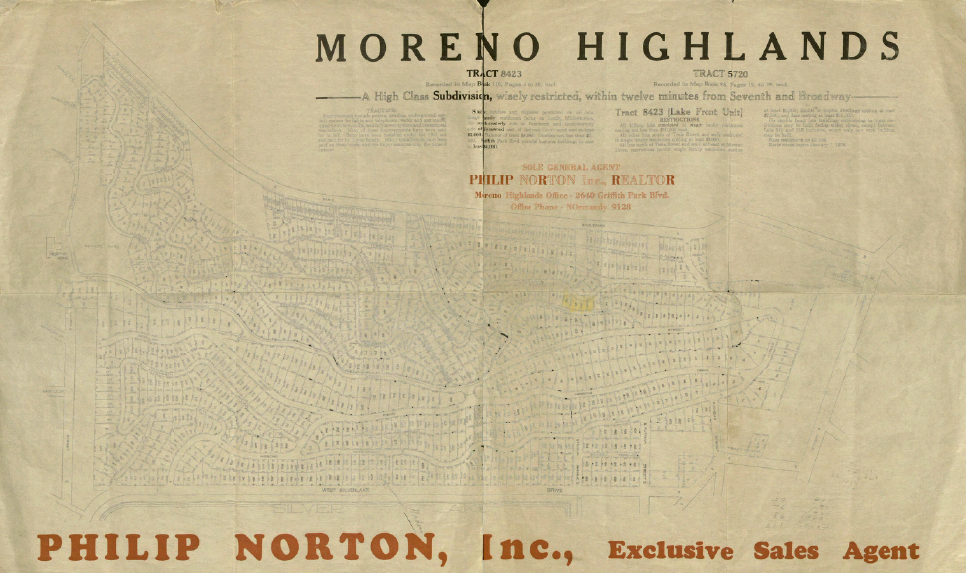

Moreno Highlands Subdivision

As LA's population grew in the early 20th century, suburban developments like Moreno Highlands popped up across the city. Located in Silver Lake, it is close to Los Feliz, the setting for Double Indemnity. Silent film star Antonio Moreno and his wife, oil-heiress Daisy Canfield, developed and styled Moreno Highlands after Mediterranean villages they visited on their honeymoon. Much like the Dietrichson house, with its popular "California Spanish" design, this suburb was styled with a coastal aesthetic that leaned heavily on an idealized fantasy past, overlooking the enslavement and genocide of indigenous people. While aesthetically pleasing and removed from the hustle and bustle of the urban core, some favored architectural styles in this period echo dark corners of our past.

View Map (PDF)

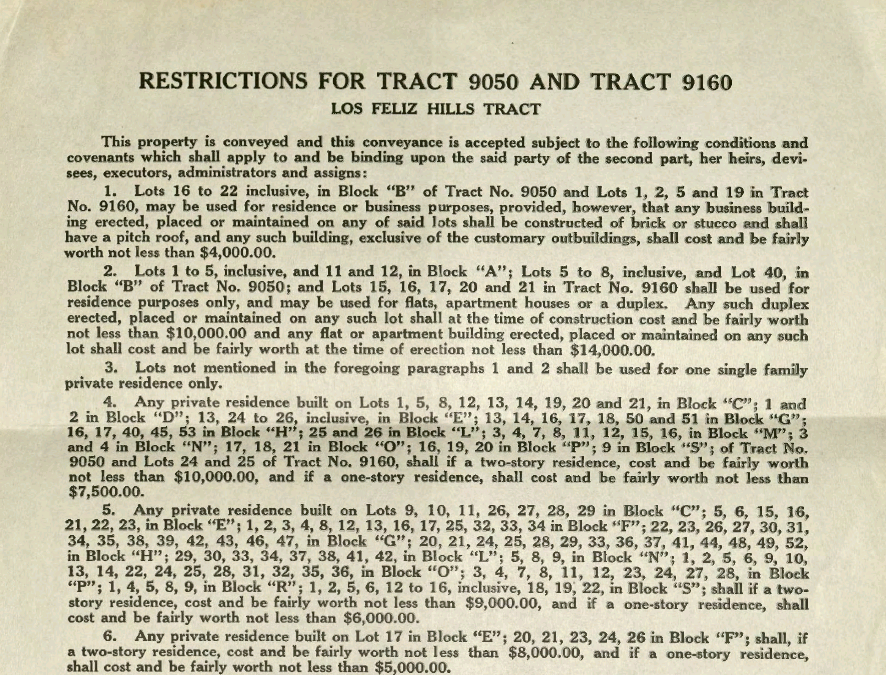

Tract Restrictions

As suburban developments spread across Los Angeles, many included restrictive covenants in the fine print. In this Tract Restrictions document from Los Feliz, Paragraph 11 restricts the property it applies to from being "rented, leased, sold, devised or conveyed to or inherited by, or ... occupied by any person whose blood is not of the Caucasian Race." Whites used racially restrictive covenants to discriminate against non-whites, preventing them from purchasing homes or living in particular neighborhoods. In Double Indemnity Neff described a suburban neighborhood by its scent, "I can still remember the smell of honeysuckle all along that street. How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?" Although murder did not lurk in most neighborhoods, the codified racism written into the very foundations of newly-constructed suburban enclaves was indeed a dark shadow over many new Los Angeles developments in the early 20th century.

View Document (PDF)

Crimes of Passion

In Double Indemnity Phyllis lures Neff into murderous insurance fraud through promises of love and a future together. Los Angeles courtrooms were familiar with crimes of passion. The Agness M. Underwood Collection contains many photographs and reporting notes from Underwood's work covering crime in the city as a court and police reporter. Helen Wills, in this photograph from the collection, murdered her wealthy broker boyfriend Harry Love, for going to a New Year's Eve party on December 31, 1936 with his mother instead of with her. A jury found Love guilty of second-degree murder, whereupon she went into a comatose state for seven days. Her condition, according to newspapers, led to the creation of the term "escape phenomenon."

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959)

An early scene in the science fiction film Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) shows the pilots of American Flight 812 sending a mayday signal to the Burbank Airport after sighting mysterious UFOs hovering over the San Fernando Valley, the beginning of an alien invasion that would spread across the United States. The aliens reanimated buried corpses in part to demonstrate their advanced technological knowledge. During World War II Los Angeles became a center of aerospace manufacturing, making the city a likely location for aliens to warn humans of the destructive capabilities advanced by military industrial manufacturing in the mid-20th century. The dream of technological innovation leading the future, with LA as a centerpiece of post-WWII industrial aviation, is positioned as a point of critique rather than progress.

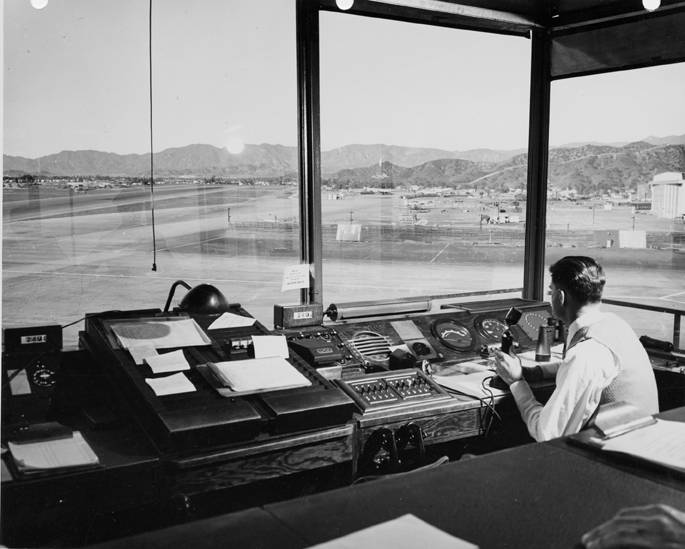

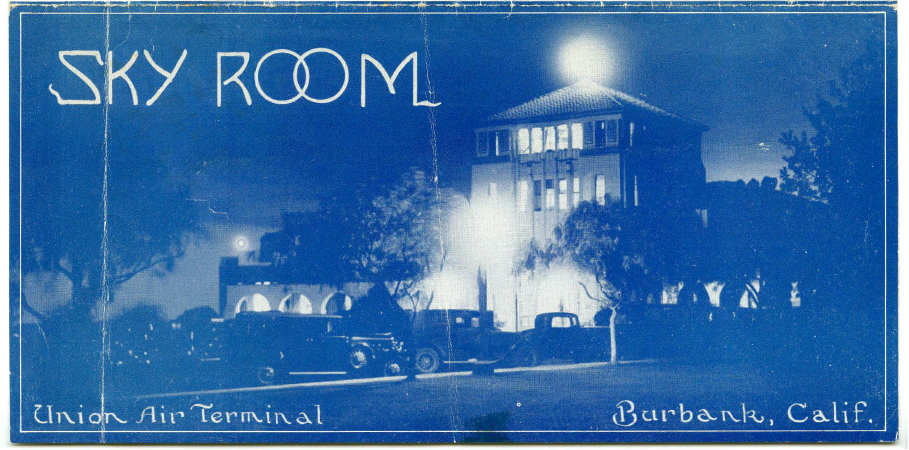

Lockheed Air Terminal

The pilots of American Flight 812 in Plan 9 from Outer Space radioed the Lockheed Air Terminal Control Tower seen here as they spotted UFOs over the San Fernando Valley. The Hollywood Burbank Airport was built in 1930 as Union Air Terminal, and initially served as Los Angeles' primary civil airport. In 1940, Lockheed Aircraft Company bought the airport and renamed it Lockheed Air Terminal, as seen from this photograph taken from the control tower. Although it would be surpassed as LA's main airport by Los Angeles International Airport after World War II, it continued as an important location for the local aerospace industry.

Loyalty Oaths

The film's protagonists fear aliens more than the alien technology seen in the sky, but the film's message is centered on the risks of rapid and partially-understood technological advancement. Atomic and nuclear technologies that helped end World War II also ushered in the Cold War, fueling intense paranoia across the US. Our paranoia focused on the communist Soviet Union, against whom the US raced to achieve further nuclear advancements. President Harry S. Truman's 1947 Executive Order 9835 required loyalty oaths and background investigations on persons deemed suspect of holding party membership in organizations that advocated violent and anti-democratic programs. This brochure from the United Defense Committee Against "Loyalty" Checks described the invasive practice as unconstitutional. Loyalty checks were not an alien invasion, though they were an invasion of privacy.

View Full Program (PDF)

Sky Room

The Sky Room was the Union Air Terminal restaurant in Burbank, and this souvenir menu shows the selection of beverages available, alongside seafood from Seattle, "Caught early in the morning--brought to us by transport plane for your dinner the same day." Increasingly accessible air travel brought the world and its goods closer together, a benefit of the technological advancements accelerated by military research and experimentation during World War II. Plan 9 from Outer Space frames these same advancements as accelerators of humans’ destructive capacities.

View Full Program (PDF)

Cleopatra Jones (1973)

At the center of Cleopatra Jones is the titular character, a strong Black woman who works as a federal agent tracking down the drug dealers and gun salesmen devastating her community. The film is considered a Blaxploitation film, a subgenre of exploitation films that depict Blacks defying oppressive systems, but often with a heavy dose of sexualized violence. The centering of Black main characters and the superhero-like qualities they possess could be read as empowering, but many Blaxploitation films perpetuate negative white stereotypes of Blacks, especially in their presentation of Black communities as places of drugs and violence. Despite these limitations, Cleopatra Jones features a strong and independent female lead character who exposes corrupt police officers and takes flak from no one. The film is a societal critique of the police as a trustworthy institution, with Cleopatra Jones, as a federal agent outside the police force, leading the charge against a corrupt system.

Deciding About Drugs

"A Woman's Choice: Deciding About Drugs" emphasizes the choices women had in the late 1970s related to marriage, children, careers, and drugs. The brochure notes, "We get a great sense of satisfaction in finding and developing our own roles in our communities. However, the normal stress in our lives sometimes seems overwhelming." The booklet positions drugs and alcohol as an escape from stress and dealing with feelings, and centers the use of these substances as an individual choice, rather than something brought on by societal conditions. The booklet provides suggestions on how to relieve stress to help avoid taking drugs, but does not address systemic issues that create cycles of drug abuse. Although exercise is listed as one stress buster to prevent drug use, the booklet's authors were likely not referring to the martial arts Cleopatra Jones employed to kick drugs and crime out of her community.

View Additional Pages (PDF)

Links, Inc.

Cleopatra Jones is a strong female character who boldly and fiercely advocates for her community. In the film, she fights to protect the B&S House. This community space serves as a home for recovering drug addicts, and a meeting space for local community members to gather and strategize on addressing the issues ravaging their neighborhoods. Although Cleopatra Jones and the B&S House are fictional, Los Angeles had and still has strong Black women leaders working to support and empower their communities. One such group is the Angel City Chapter of Links, Inc., an African-American women's and family organization that works for the educational needs of children and young adults. Ten Links, Inc. members who had moved to Los Angeles from other parts of the country founded the Angel City Chapter of Links, Inc. in Los Angeles in February 1963. The Angel City Chapter supports community-based institutions by sponsoring fundraising events, educational awareness projects, and related benefits.

Achiever Program

The Angel City Chapter of Links, Inc.’s Achiever Program was created to implement "the Link national commitment to education, cultural and civic improvement in our society." Through the Achiever Program, local chapters connect with the Links' national program of "Services to Youth, National and International Trends and Services, and The Arts." The program provides leadership training, community responsibility, and comradery for thirty-five young Black men each year, and intends to provide an encouraging group identity and sense of belonging, while applauding individual accomplishments. While many Black communities in 1970s Los Angeles wrestled with drug issues as in Cleopatra Jones, it is a disservice to the multifaceted stories and lives of Black Angelenos to center stories of Black triumph and success on drugs and violence rather than on community strengths like those demonstrated by Links, Inc. and their Achiever Program.

View Full Program (PDF)

Chinatown (1974)

In 1937 Los Angeles, a woman calling herself Evelyn Mulwray hires J.J. "Jake" Gittes to investigate Hollis Mulwray, chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. In the course of his investigation, Gittes learns that the water department is sabotaging farmers' water supply in the Northwest Valley in order to buy their land at a reduced price. This water conspiracy land grab plot is loosely based on real events at the dawn of the 20th century when the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power gained control of most of the Owens River to supply a growing Los Angeles with water. Feats of great civil engineering that tamed the land could be portrayed and simplified as "progress." Yet the spirit of the California water wars captured in Chinatown lays clear the complexities of the idea of progress, especially who is actually served when ecosystems are decimated by engineering marvels, farmers are left out to dry, and those that propelled the project forward are untrustworthy and egotistical. The optimism of progress is placed under a cynical shadow.

L.A.'s Dark History as told through Chinatown and Library Archives

L.A.'s Dark History as told through Chinatown and Library Archives (Audio transcript )

Bringing LA to the Water: The Past and Future of LA's Water Problem in Polanski's Chinatown

Bringing LA to the Water: The Past and Future of LA's Water Problem in Polanski's Chinatown (Audio transcript )

Nate Duchene's Chinatown podcast

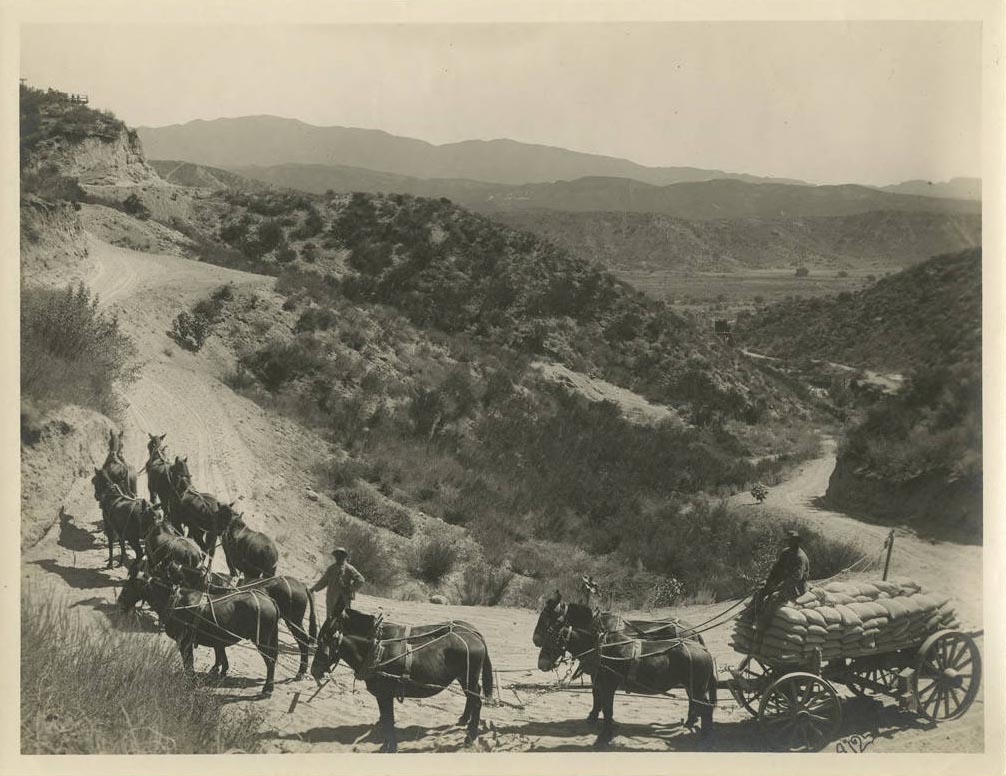

Aqueduct Construction

William Mulholland was the engineer responsible for building the 233-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct that brought water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles. The diversion of Owens Valley water supplied a growing Los Angeles with an essential utility, but ruined the Valley's farming economy. The aqueduct was completed in 1913, but wrestling control of the water rights took years of political maneuvering. In the film, Hollis Mulwray, chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, stands in for civil engineer Mulholland. Unlike in real life, Mulwray is against the construction of water infrastructure, and refuses to support the construction of a reservoir as he views the dam construction portion of the project as unsafe. This is likely a reference to another of Mulholland's water infrastructure projects, the St. Francis Dam, which collapsed in 1928 shortly after its completion, killing over 400 people.

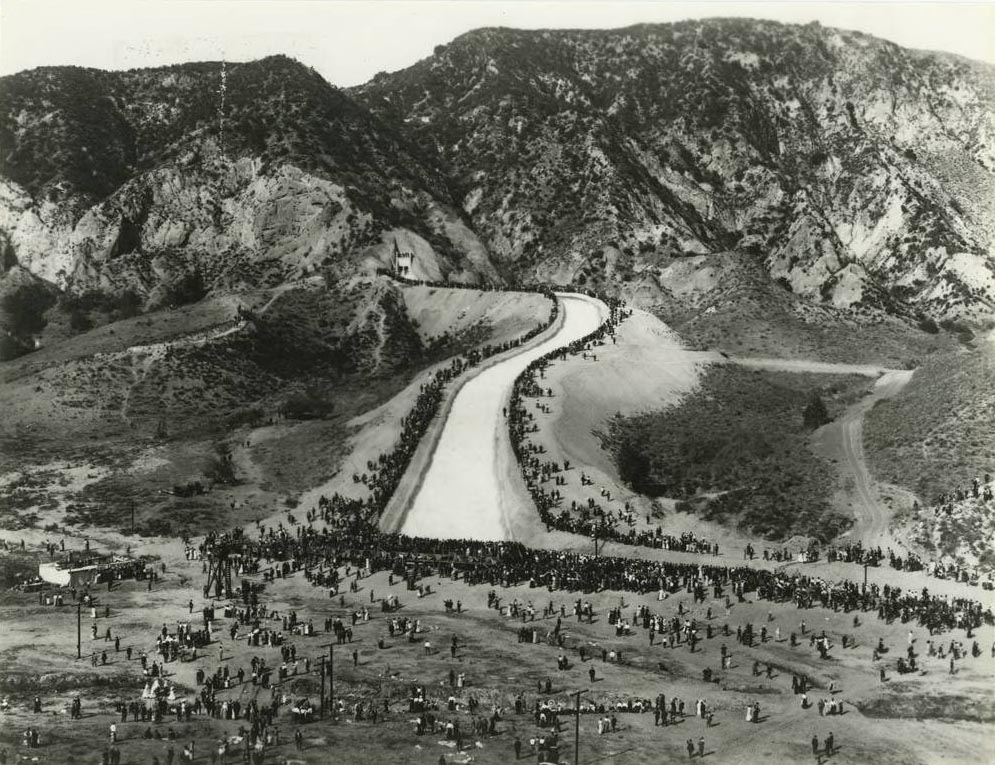

Aqueduct Opening Day

On November 5, 1913, the Los Angeles Aqueduct began bringing water to Los Angeles, as seen in this opening day photograph. After the arrival of aqueduct water, many towns in the San Fernando Valley began to approve annexation to the City of Los Angeles so they could use the municipal water system. In Chinatown's Los Angeles, wealthy investors with inside information manufactured a drought and secretly purchased land in the San Fernando Valley from desperate farmers, knowing that it would be worth much more than they paid for it once water availability increased with the construction of additional water infrastructure. In early 20th century Los Angeles, wealthy individuals did invest in land in the San Fernando Valley, although the degree of actual conspiracy is debated. As a vital commodity to life and urban growth, the control of water propels rumors of conspiracy dealings in both Chinatown and the real Los Angeles.

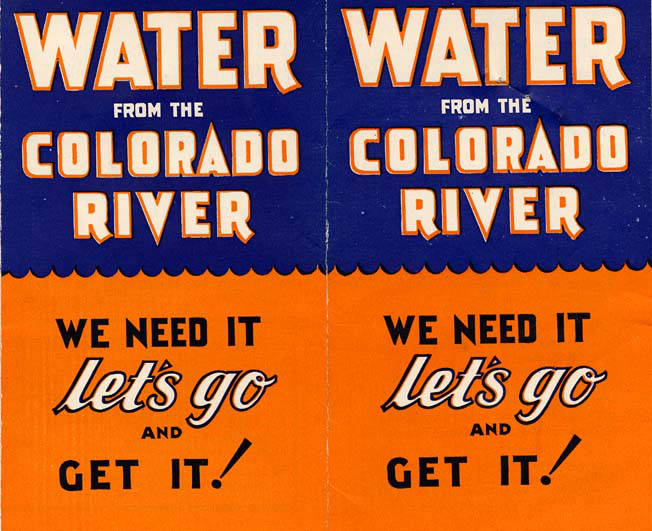

Colorado River Water

At the opening ceremony for the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913, William Mulholland declared of the water flowing through it "There it is. Take it." Nearly 20 years later, this brochure urged readers to go after water from the Colorado River. Andrae B. Nordskog published weekly Los Angeles paper The Gridiron, which often published articles and editorials championing the Owens Valley's cause and criticizing the City of Los Angeles. He became President of the Los Angeles-based Southwest Water League (SWL) in 1930, and led the organization for over 30 years, making recommendations on aqueduct and reclamation projects. This brochure from his papers advocated for the construction of the Colorado River Aqueduct. This project was undertaken by the Metropolitan Water District, incorporated in 1928 to represent cities throughout southern California. Work began on the project in 1933 and water first flowed in 1939. The Colorado River project was contemporary to the setting of Chinatown, and demonstrates that the Los Angeles Aqueduct is only one element of the tension and debates around water access in California and the west.

Blade Runner (1982)

Blade Runner is set 37 years in the future, in a Los Angeles of vertical density, diversity, advertising clutter, and flying cars. In 1982's version of the year 2019, Rick Deckard works as a blade runner, a special police bounty hunter with a mission to track down and "retire" bioengineered human look-alikes known as replicants. The Los Angeles of Deckard's 2019 is no longer a destination of endless opportunity and hope. It is instead an urban dystopia where replicants hide from persecution. Replicant Rachael asks Deckard whether he has ever accidentally retired a human mistaken for a replicant. In this Los Angeles, as in real Los Angeles, the lines between real and manufactured, and right and wrong are blurry. Deckard begins his replicant mission with the conviction and focus of a professional, but along the way he starts to question the system he operates within. Although neo-noir Blade Runner is set in the future, the technological advancements that transpired to enable flying cars, giant floating advertisements, and other futuristic technologies are framed by the film as examples of broad societal decline rather than elements of progress.

Blade Runner and Replicants

Living in Fear: A Lesson on Humanity Through Slavery in the 1982 Film Blade Runner

Living in Fear: A Lesson on Humanity Through Slavery in the 1982 Film Blade Runner (Audio transcript )

Queer Times in a Dystopic Future

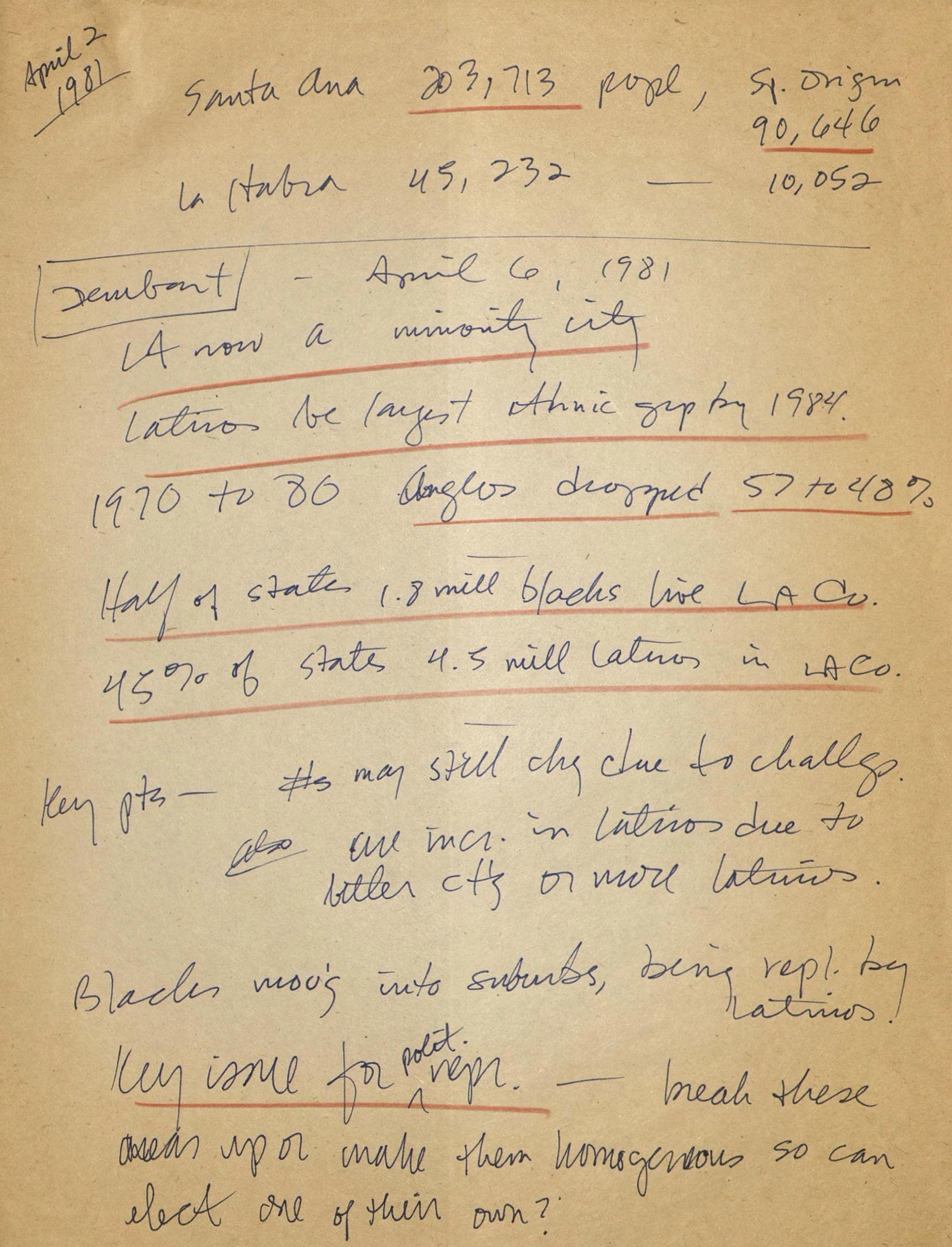

Demographics

Blade Runner portrays Los Angeles as an Asian-influenced city, with business signs and advertisements dominated by Japanese characters and imagery. This reflects Los Angeles as a city on the edge of the Pacific, concerns about Japan's rise as an international economic powerhouse, and increased immigration from Asia that followed U.S. involvement in wars in Southeast Asia and from passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Despite this 1982 vision of 2019 Los Angeles, in the early 1980s LA's Spanish-speaking population was growing into the dominant demographic in Los Angeles County. Frank del Olmo was a journalist, editorial columnist, and editor for the Los Angeles Times specializing in Latin American affairs and local Latino community concerns. This page of notes comes from his research files on demographics in Los Angeles in 1980-1981. He writes that, "LA is now a minority city" and that "Latinos [will] be the largest ethnic group by 1984."

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

Administrative Advocacy

The mission of the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) is to serve local government officials in Southern California. SCAG's Administrative Advocacy program offered a chance to do something about "ill-considered federal regulations [that] are needlessly running up costs for your community." The program aimed to prevent red tape, during a national wave of deregulation and questioning of existing government infrastructure. In the 1970s, disillusionment and a lack of trust in federal politics was on the rise with the Watergate scandal, the fall of Saigon, the hostage crisis in Iran, and national gasoline shortages. Similarly, disillusioned and lacking trust in the government he works within, Deckard ultimately rejects his order to "retire" all replicants by killing them, and flees with replicant Rachael.

View Full Program (PDF)

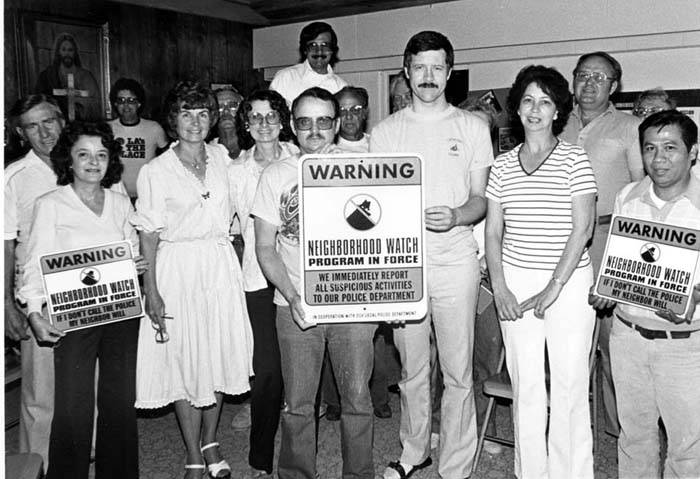

Neighborhood Watch

Civil unrest in the 1960s and passage of President Lyndon B. Johnson's Law Enforcement Assistance Act in 1965 led to a rise in fears about suburban crime and the militarization of police operations. These fears and an escalation in local policing continued into the 1980s, with crime control and incarceration seen as the central response to poverty and inequality. Parallel to this, the National Sheriffs' Association started the Neighborhood Watch program in 1972 as a way for local citizens to help address neighborhood problems. While Neighborhood Watch virtuously intended to ensure community safety, bring neighborhood residents together, and increase quality of life, it also had the potential to lead individuals into vigilante justice and dangerously ostracize those that did not fit the neighborhood profile. This mix of paranoia about crime, vigilantism, and taking personal responsibility for society's problems comes through in the dark violence of Blade Runner and its complex and sympathetic portrayal of replicants as "other."

Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Set in 1947 Los Angeles, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a live-action-animation crossover film where people and "toons" interact. Detective Eddie Valiant is pulled into a murder mystery plot and tasked with finding out who is attempting to frame cartoon star Roger Rabbit. Valiant is cynical and distrustful of toons, and operates on the fringes of regular toon and human society. As he investigates the case, it soon becomes clear that the investigation is only the surface of a much deeper plot involving the real villain, Toontown’s corrupt superior court Judge Doom. Doom, with the assistance of his shady Toon Patrol police team, devises a way to kill the previously indestructible toons, destroy Toontown, and claim their land himself. Doom's foreknowledge of the city’s plan to build a freeway system leads him to buy the Pacific Electric streetcar system with the intention of making a large profit. The film takes a fact-derived myth, the long-held (though false) General Motors streetcar conspiracy, and turns it into a credible noir fiction plot.

Internalized Racism in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Internalized Racism in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (Audio transcript )

LA Transportation and Social class in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

LA Transportation and Social class in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (Audio transcript )

Lilit Grigoryan's Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Podcast

Lilit Grigoryan's Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Podcast (Audio transcript )

Mirror Mirror in the Hollywood Studio

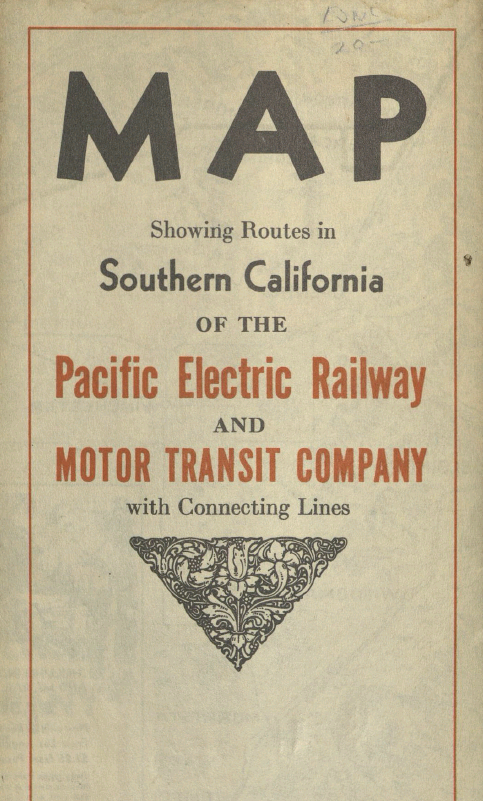

Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway, also known as Red Cars, was an extensive privately owned mass transit system that operated in Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, and Riverside counties. The first Southern California line opened in 1902 between Los Angeles and Long Beach. The railway system operated at a loss offset by profits from part-owner Henry Huntington’s real estate developments. As development opportunities dwindled, Huntington converted less profitable lines to bus lines beginning as early as 1925, with other service cuts coming in the late 1930s. While these cuts occurred, city planners were developing the future of the Los Angeles freeway system. The city began acquiring the land necessary in earnest in 1951. The Metropolitan Transit Authority purchased privately-owned transit systems and began running a single unified system in 1958.

View Document (PDF)

View Accessible Text Transcript (PDF)

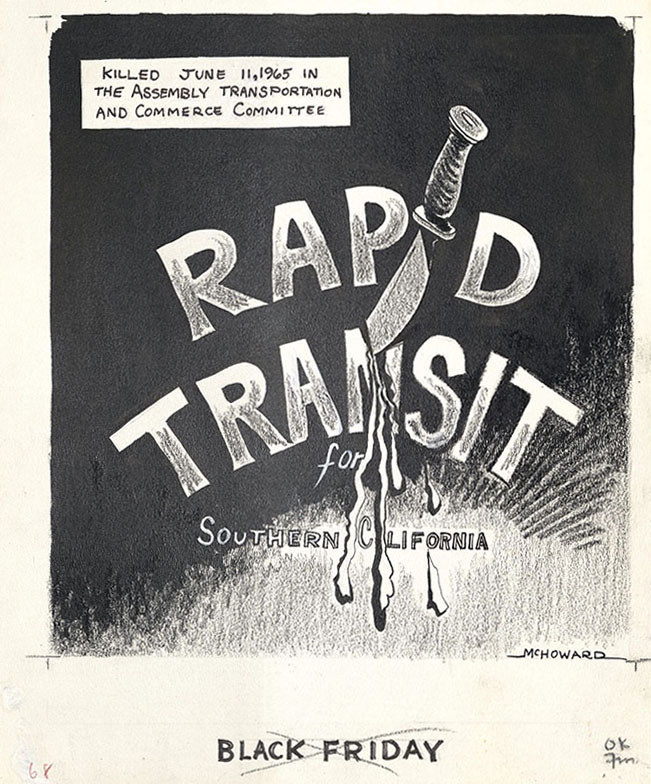

Rapid Transit

This political cartoon, drawn by Merle H. Cunnington while on staff at the Van Nuys News & Green Sheet, illustrates the ongoing discussion surrounding the need for public mass transit in Los Angeles. In Who Framed Roger Rabbit Judge Doom plots to cut a freeway through Toontown. In this illustration, a cartoon knife cuts into the heart of Southern California rapid transit. It was published seven years after the Metropolitan Transit Authority began operating the public transit system. This conversation endures to the present as the balance between private auto ownership and freeway expansion battles with public transit expansion.

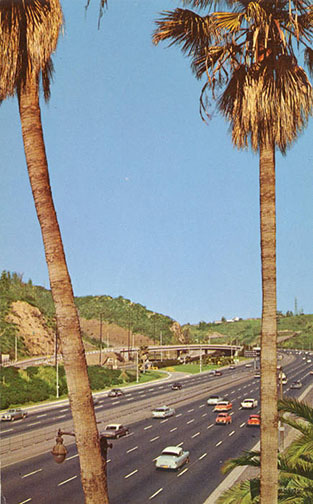

Hollywood Freeway

This 1950s postcard shows the Hollywood Freeway, the 101, through the Cahuenga pass. The bulk of the original construction of Los Angeles’s extensive freeway system occurred between 1947 and 1965. These early days of the freeway system saw a boom in the city’s "car culture" without any sinister help from Judge Doom as the culprit of the Red Cars’ demise. Pacific Railway’s Red Cars continued to travel between downtown and the San Fernando Valley via tracks running down the center of the freeway until 1953. Their removal was the first step in the freeway’s expansion that accommodated an extra lane of traffic in either direction beginning around 1954.