Newsletter Edition: Fall 2022

Contributed by Elizabeth Altman

Artists, club members, family and friends gathered October 9 at the opening reception for “The Politics of Low & Slow,” an exhibition of lowrider history, art and culture in the Los Angeles area. The exhibit features car club memorabilia, representations in media, paintings commemorating the lowrider car enthusiasts, and much more. We spoke with our guest curator, Professor Denise M. Sandoval, for an inside perspective on the exhibit.

You’ve curated similar exhibits on lowrider culture. What motivated you to mount an exhibit at CSUN?

When Ellen Jarosz asked me if I’d like to do an artifacts exhibit, I jumped at the opportunity. I had always hoped to do an exhibit about Los Angeles because doing this research as long as I have, a lot of my lowrider friends are natural historians, and they keep collections of everything.

What’s different about this exhibit?

The contributors’ personal archives reflect not just organizational history, but their personal role in the culture. On one hand, it’s always fascinating to explore the personal connections that people have to objects because of their love of lowrider culture. And on the other, this is the first time I’ve worked at telling the story through artifacts, because typically with my museum exhibits, the highlight is on the car. Since we can’t roll a ‘64 Chevy in here, I needed to tell the story by looking at what happens around the car and what celebrates the car. We’re also including car shops, all the blood, sweat and tears that it takes to build the car: the people that build the cars, the painters, and the people that install hydraulics.

What were the challenges involved in this new approach?

The complicated part was choosing which artifacts were going to tell the story. Not everything makes it into the cases. And then you have to decide where everything is laid and how it is positioned. There are so many different lenses through which to look at lowriding, and as well as different themes. The car is not only an object, but it's a living culture, and people make meaning out of it. What happens when we look at that body from the inside? What about the technical parts? What are lowrider clubs, what is cruising like, what is women's role in lowrider culture?

What do you think students will take away from this experience?

This exhibit includes a lot of artifacts that I've personally collected since 1998, so I'm also part of the story. The educational component is that it visualizes my journey as a researcher, and the work that I've been doing for all of this time. It's a true collection of the interrelationships that happen between the researcher and the community I study, but more importantly, of the relationships and friendships that I’ve built with that community.

What do you think this exhibit says about the relationship between life and art in the Chicana/o/x lowrider culture?

The lowrider car has a history of representing Chicano history, as well as expressing pride in being Chicano in Los Angeles, and so it has become an icon in the artwork of prominent Chicano artists. We’re very lucky to have the maestro, Frank Romero, whose mural “Going to the 1984 Olympics'' featured lowriders. The art portion of the exhibit was a way to bring artists into the discussion, to think about how they see lowrider cars and the way the cars reflect their view of the culture - and what it means to them. A lot of the artists are lowriders themselves, like the CSU Long Beach alumn who painted her club on the fender. And the Perez brothers: their father was a lowrider, so they grew up in the culture. They’re part of this younger generation that is continuing the work of people like John Valadez, one of the Chicano godfathers of art, who started painting lowriders in the ‘90s.

What do visitors need to know about the relationship of lowrider culture to the Chicano/a/x experience?

I grew up in the San Gabriel Valley, in La Puente, which had a lot of lowriders. From a really young age, before I had the language to help understand the community I was living in, I always knew it was an important story. In Los Angeles, in particular, lowriding was how black and brown communities began to express their notions of what it means to be American, and also highlighted their cultures front and center in LA. The cars are these canvases of creative expression, but they also carry within them those tensions of race and class that existed in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. There’s your car, which is that symbol of the American dream, but it is also your mobility, and can also provide you a space to visualize your culture and your community.

What meaning does Lowrider magazine bring in this exhibit?

When it was created in ‘77, Lowrider magazine really became a community space for Chicanos in the barrio to begin to talk about their lives on their terms. And you sort of see those discussions happening in the letters to the editor, how prideful they were having this magazine. Photos of the communities featured in Lowrider just were not featured in the dominant media at that time. And so I think it takes us back to a time before this generation of social media, when magazines were the way that we communicated our message to the world and built community. When we look at it now it becomes that classic image of lowriding, the nostalgia, that memory of what lowriding used to be - the golden age of lowriding.

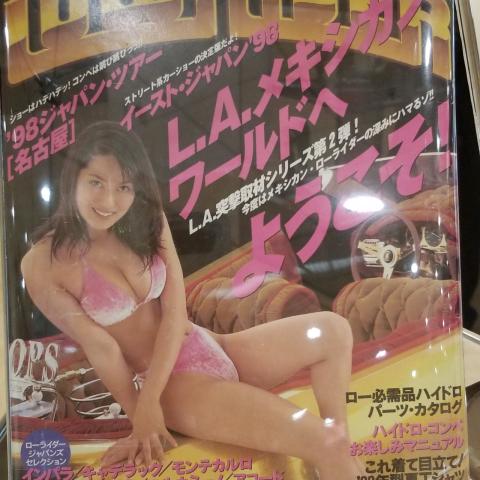

How did the Japanese lowrider magazines become part of this story?

I bought this Lowrider Japan magazine at Tower Records in 1998 and it kicked off my research. Japan started participating in lowrider culture in the late ‘80s. One of my friends who worked for Lowrider Magazine, Takashi, his dad loved hot rods in the 50s, and he moved to LA because he was drawn to lowriding. He ended up writing stories and taking photos, creating that bridge for Lowrider Japan. Japan was that first international space that really celebrated lowriding, and specifically Chicano lowriding, using the fashion, style, the music… They started to have their own shows, and began to bring lowrider cars from LA over there. Some of my friends like Mister Cartoon and Esteban [Oriol], started going there in the 90s to take pictures and do tattoos with low rider iconography. Today, Japan is respected as an important part of the lowrider community. My friends that are builders out here in LA say Japan is building award winning cars right now.

How would you say lowrider culture has changed since the 70s? How are the youth now embracing it?

Lowriding is the biggest it’s ever been. I think the pandemic sort of gave it a shot in the arm because people were looking for safe things to do and cruising was a safe space. Cruising events are so popular that people will show up that don’t even have cars, just to participate in the scene. It’s really expensive to build lowriders, especially in California. People are dropping $100,000 - $200,000 on a car, to build it and customize it. So, I think the larger question is, if older cars have become more expensive, how do you create a space for younger folks to participate in it? If you grew up in the scene, you're kind of part of that generational history already, but it might be hard for you to buy an old car and put in all that money to customize. So, there's a loss of younger members in car clubs now - everybody's 35 years and older, because of the expense. Some clubs and events are starting to relax the rules and let people bring in cars that they drive. So now today instead of ‘39 Chevys there's a revival of Mazda and Toyota mini trucks from the ‘80s. Each generation sort of has to figure it out. But at its core, you know, the themes of lowriding are always family, pride, honor, respect, brotherhood, whatever generation you're in.

Do you have a lowrider?

I've always wanted a lowrider, but it takes money. And now I think it's going to happen because I've been talking about getting a car that I can mural with Chicana history. Women have always been part of the scene – they’ve been solo riders, even if they weren't accepted in the male lowrider clubs. But now some clubs have turned coed, a couple of them in LA, and there are some all-female clubs too. In the last six, seven years, women have come in in full force. I really feel they're the future of lowriding, and now we're in a space where there are women builders, women painters, so I could actually have women work on the cars, that would be great.

How do you think this exhibit will enhance the relationship between the Chicano/a/x community in the valley and CSUN?

I'm really excited to have this exhibit in my academic home, and I think it's a great way of bringing folks that haven’t necessarily ever come to our campus. I'm really excited that high school and junior high students can come into this space. It's really important, because it builds that bridge to the community that we serve, which includes a large lowriding community here in the valley. And it’s also introducing our CSUN community to something they aren’t as familiar with. Maybe they know what a lowrider car is, but they don't know all of that history. I'm excited about opening up our home here to the community, and it's going to be really interesting to see people's reaction to it.

Click on the images below to see more images in our image gallery.