Newsletter Edition: Spring 2020

Contributed by Gina Flores

In this Oviatt Spotlight, we’re zooming in on a significant project in the Library's Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, where the talented team is digitizing thousands of images by American photojournalist Richard Cross. This Q & A with Dr. José Luis Benavides takes us behind the scenes of this project.

Benavides is a journalism professor and the director of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, formerly known as the Institute for Arts & Media at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). He created the first interdisciplinary minor in Spanish-language journalism in the United States, and established the Spanish-language student publication, El Nuevo Sol in 2003, which he transformed into a digital site covering global Latino communities in 2007.

Q. How was the Richard Cross Collection acquired?

A. The Richard Cross Collection (RCC) was donated to CSUN by his father, Russell Cross, a resident of the San Fernando Valley until he passed away. Since Richard’s death in 1983, his father looked for a place to house his son’s photographic collection. Dr. Kent Kirkton, then director of the Center for Photojournalism & Visual History, a precursor to Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, persuaded Mr. Cross to donate his son’s collection to CSUN for preservation and eventual dissemination.

Q. What is the significance of the collection?

A. The RCC consists of thousands of prints, slides, and negatives by Richard Cross. His photographs in Colombia and in Central America and Mexico compose the two largest segments of the collection. Prior to receiving funding, the RCC remained undigitized (except for a small sample of 14 images), dramatically restricting its availability to the public. In 2018, the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center received a $315,000 grant from the National Endowment of Humanities to digitize and create metadata for 11,200 images.

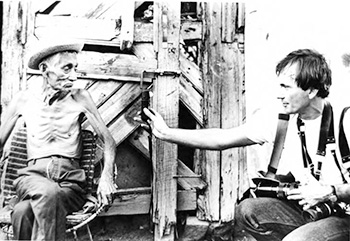

The RCC photographs of San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia, for example, are significant because they are the only extensive visual record available of all aspects of life and cultural practices in this community, which was originally established by runaway slaves. These images, taken between 1975 and 1978, preserve a trove of imagery depicting a community of people of African descent whose traditions were established in the 16th and 17th centuries, mixing African and European influences. These images document every aspect of life: landscape, architecture, interior design, transportation modes and routes, clothing, hair styles, cattle ranching, bullfighting, funeral practices, farming, cooking, religion, festivities, warrior culture, and entertainment. Nothing else like Cross’s extensive visual documentation of Palenque has ever been attempted before or after.

These unique images are important not only because there is a longstanding absence of extensive visual representations of everyday life in Black communities in the Americas, but also because they were created with, and for, the community to foster a deeper understanding of the culture of the people of San Basilio. Cross worked with the explicit consent of the community, who received regular updates about his work. His images were the first and only in-depth look at Palenque, which later gained more prominence in Colombia and the world, and was proclaimed by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2005. Two hundred sixty photos by Cross were included in the book, Ma Ngombe: Warriors and Cattle Ranchers from Palenque, published in 1979 as a collaboration between Cross and Colombian anthropologist Nina Friedemann. Anthropologist Jaime Arocha, a colleague of Friedemann in Colombia, describes this book as “one of the main world classics of visual anthropology.”

The RCC images of Central America and southern Mexico preserve the memory of civil wars and conflict for people living in that region and for people of Central American heritage living in Los Angeles and other parts of the United States. From 1979 to 1983, Cross did significant photojournalistic work as a stringer for the Associated Press and major news publications in the U.S. and Europe, covering wars and turmoil in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, as well as the Guatemalan refugee crisis.

Cross was one of several notable American photojournalists working in Central America, including Susan Meiselas, Harry Mattison, and John Hoagland. But none of these photographers’ collections has been archived and digitized for public use. In Nicaragua, the images captured gun battles in the streets, adolescent Sandinistas carrying rifles, and the suffering of civilians due to military bombings and street violence. These images were published by dozens of newspapers around the world and helped chronicle the last stages of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua. In El Salvador, Cross’s pictures portrayed all aspects of the internal conflict: military and paramilitary groups, U.S. advisors, guerrillas, barricades, the 1982 Constitutional Assembly election, and everyday life in the country during that time of turmoil. In Guatemala, Cross chronicled the escalating effects of the military counter-insurgency operation in Guatemala City and the countryside, as well as the refugee crisis that followed, when over 100,000 Mayan peasants fled to Mexico, 47,000 to the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. Finally, in Honduras—where he was killed—his work showed the activities of U.S. advisors and the activities of the anti-Sandinista rebels (Contras), who used Honduras as their base of operation.

In whole, the RCC displays the versatility of work performed by Cross, as well as the ways in which he synthesized different modalities of photographic work. Dr. Richard Chalfen, Cross’s academic advisor at Temple University, has written that Cross recognized the “differences between photographs made by tourists, visual journalists, fine art photographers, and/or visual anthropologists, and realized that each one of these tasks required different kinds of questions and different kinds of processes to achieve the desired product.” Cross’s images, and the stories they tell, offer avenues for current generations to understand their histories and identities, and can contribute to cross-cultural compassion and understanding.

Q. How does the collection impact students and faculty at CSUN?

A. The Pew Research Center estimates that Los Angeles County has the largest concentration of Salvadorans (more than 350,000) and Guatemalans (more than 200,000) in the United States. Today, the United States has more than 5.2 million people of Central American heritage, with Salvadorans recently surpassing the number of Cubans in the country to become the third largest Latino group. CSUN has the only Central American Studies program in the nation, and a significant portion of our student population is of Central American heritage. We are thus particularly well suited to preserve the memory of the events that triggered the migration of Central Americans to this region—including our students, their parents and professors, and many of the students and parents in the K-12 schools in the area.

For Americans of Central American heritage, the significance of the conflicts documented by Cross’s photographs cannot be overstated, as those conflicts triggered refugee and migratory processes whose effects continue into the present day. Cross’s Central American images can assist in improving cross-cultural understanding of communities bearing the legacies of those armed conflicts, and in so doing, may lessen interethnic discord and polarization that have become a central challenge in national life.

This collection has inspired student employees in the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center. One student, Marta Valier, is doing her thesis on a series of oral histories of people from Central America who lived during that time. She is preparing a short audio piece on people’s reactions to the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero in El Salvador, the historical event that escalated the war in the country.

Another of our students, Guillermo Márquez, is preparing an essay to be submitted to a journal on Richard Cross’s photos of Rosario Ibarra de Piedra, Mexico’s indefatigable mother whose son was disappeared by Mexican authorities during the dirty war in Mexico.

I also help coordinate the work that Dr. David Moguel from the College of Education is doing, creating a curriculum component using Richard Cross’s images of Central America. This curriculum will be available in digital form, thanks to the work of Professor Joe Bautista and students in the Art Department, for use by middle- and high-school teachers in Los Angeles and other parts of the country. Finally, I also coordinate with the members of an international advisory board of scholars and photographers in Colombia, Central America, and the United States, who have supported the work we are doing by helping identify subjects and situations in the photographs, disseminate their availability among scholars, students, and the public in general.

Q. How are things coming along with the digitization project and promotion of the RCC?

A. We currently have a total of 5,807 images published, 1,463 images awaiting subject assignments from catalogers, for a total of 7,270 images either complete or in the queue. I oversee as well the museum exhibitions done with these images. We have had until today, two museum exhibitions with the images of Central America: one at the Museum of Social Justice here in Los Angeles (August 2019–January 2020), curated by me and Professor Edward Alfano, and a second exhibition at the Museum of Word and Image in San Salvador (January 2020–present), curated by the museum’s director Carlos Henríquez Consalvi.

As part of the work of the grant, I have also coordinated the visit of a number of international speakers, whose expertise is connected to this and other collections of the Bradley Center. Margarita Montealegre is a good example of this. She met Richard in Nicaragua while he was working there. Margarita helped us identify subjects and places. We recorded an oral history with her to add to the collection.

Come discover the Richard Cross Collection in our Tom & Ethel Bradley Center Photograph Collection, which is part of the Oviatt Library Digital Collections.