Newsletter Edition: Fall 2024

Contributed by Gina Flores

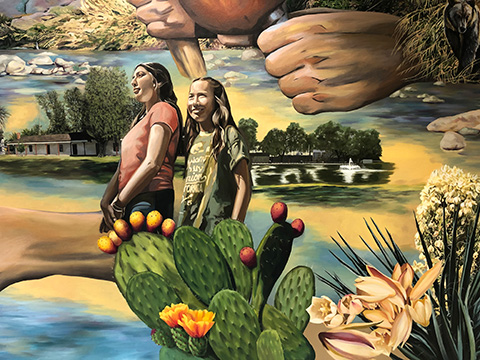

Lindsay Carron is a distinguished artist known for her vibrant murals and dedication to social and environmental justice. She was selected by an American Indian Studies and Art Department faculty juror panel to create the Tataviam land acknowledgment mural, entitled “The Continuum of Time” in the University Library at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). Carron’s work often bridges the connection between communities and the land, drawing attention to indigenous cultures and environmental preservation. Her thoughtful and intricate designs reflect a deep respect for nature and indigenous history, making her an ideal choice for this significant project that honors the Tataviam people and their ancestral land.

In this interview with Lindsay, you will learn about her collaboration with Tataviam leadership and the CSUN community. Through immersive research and creative techniques, Carron worked with CSUN students and faculty to create a lasting mural that bridges generations and celebrates resilience, while connecting the present and past.

Tell us about you and your pathway to art.

I grew up in Wisconsin, and my best childhood memories are those spent outdoors and creating art. My education path led me to traveling West to attend Pepperdine University to study art, psychology and Spanish.

I discovered the use and impact of art in communities during my travels in South America as a college student. After graduating, I continued to be compelled by opportunities to visit new communities, meet people and discover the land, and share creative projects. I experienced many growing pains as I attempted to be a working artist in Los Angeles, but the most major leaps in my growth occurred when I organized and carried out mural projects in communities abroad, such as Vicente Guerrero, Mexico and Kenya.

My learning style is through experience, and embodied knowledge has served me throughout life. With my artistic endeavors I’ve typically just made the leap and tried it out, often times meeting big challenges, but that’s part of the learning. A lot of my experiential learning related to mural painting and public art happened when serving as an artist assistant to Lydia Emily in Los Angeles. Since graduating, I have completed public art projects in Malibu, El Segundo, Culver City, Los Angeles, Mexico, Kenya, San Juan Island, and Alaska.

My work is about people’s connection to land and how this connection enters all aspects of life: culture, economy, work, play, child rearing, language, food, and way of being. My interest lies in human connection to place, and how this connection fuels and generates our lives.

How did you discover this project, and how did your vision unfold?

A friend and fellow artist and graduate from Pepperdine, Dominique Ovalle turned me on to the Cal State Northridge University Library mural project and suggested that my work would be a good fit. I had been facilitating creative projects within Alaska Native communities across the state of Alaska for eight years, and I felt strongly about doing similar work locally in Los Angeles. My family and I had just moved to the top of Topanga right above Woodland Hills, and I was eager to learn about the ecology, history, and land connection in the valley.

After the initial Call for Artists, I selected to design a proposal for the mural, and I began researching and spoke with Tribal Vice President Mark Villasenor to help clarify my vision. My goal was to celebrate tribal connection to the land of Northridge, bring to light aspects of history while also landing the vision of the mural in the present moment, representing the Tataviam past, present and future. My first sketch for the mural showed this time continuum through the spiraling of Tataviam woven baskets across different landscapes. The vision changed quite a bit from the first iteration, but the concept of a continuous flow of time is still very present. The central image of the final design are two hands reaching across the Los Angeles River. One is the hand of an elder, and the other is the hand of a young person. This motif is meant to symbolize the exchange of information between generations and the continual flow of knowledge across time.

Tell us about your experience working on the mural.

One of the most important aspects of working on the mural concept was that it represented the Tataviam respectfully, truthfully, and accurately. In order to do so, I had several meetings with Tataviam leadership to confirm aspects depicted in the mural. The exchange was fruitful and generative, and the feedback positive. I was trusted with my vision while also very willing to give it all up and go back to the drawing board. My process involved visiting sites around the San Fernando Valley of importance to the Tataviam. This included Los Encinos State Historic Park and Vasquez Rocks. These visits, coupled with my research, gradually led me to seeing the Valley with new eyes. When I went on hikes and looked over the Valley and San Gabriel Mountains, I saw Tataviam history written over the landscape: the many beauties and challenges therein.

I also received guidance and council from a team of professors at CSUN: Mario Ontiveros, Samanatha Fields, and Alesha Claveria, who were all on the judging panel and lent their expertise to the creation of the call for art. The project overall was championed and overseen by Library Dean Mark Stover and assisted by Regina Flores in administration. It has been a joy to work with this team.

One of the challenges presented in the project proposal was to create a mural that could be removed from the wall. I had recently completed a mural on material called polytab for El Segundo Public Library, so I chose this material for a removable surface. I consulted with SPARC, (Social and Public Resource Center in Venice), who is at the cutting edge of mural creation, restoration, and preservation in Los Angeles, and worked with SPARC teammate Kuva Zakheim to install two layers of polytab, 10 panels total, on the curved library wall. The panels were installed like wallpaper, and can be removed. The top layer of polytab was printed with the mural sketch, which expedited our painting process and gave us an amazing template to work from. I learned a great deal in this process and would definitely do it again for another public art project.

Because this is a community project, it was important to me to be working on the painting live in the library where students and the public could interact with me and see the process unfold. During my painting days at the University Library, I had many fruitful conversations with passersby and was able to share about what was represented in the mural about the Tataviam. I especially loved getting to know some of the people who used the Creative Maker Studio space daily.

How did you immerse CSUN Art Department students and others in the mural creation?

An aspect of the project that interested me a lot was how I could involve different parts of the CSUN and Northridge community. I knew this project required assistants, and I aimed to hire locally. I reached out to the art professors at CSUN University to share a hiring post, and I hired MA student Harmony Vasquez and MFA student Audrey Higa. Harmony and Audrey assisted in the process of the mural from the installation of the polytab to sealing the mural after painting it. They contributed immense talent, and we had a lot of fun painting and learning about each other.

Additionally, I hired and worked with CSUN recent graduate Mariana Bonilla from the Creative Maker Studio on text design and Guillermo Cuevas from the CSUN print shop to install the text panels. I partnered with Tribal Senator and CSUN employee Jesus Alvarez during the Artist Talk and for the upcoming Native Plant Walk. To be able to resource support from the University community on this project brought a certain stability that I haven’t experienced often in public art, and it was much appreciated.

What was your key takeaway from this project?

From start to finish, the project took 16 months. This is what an in-depth community project actually takes, and I’m grateful for the time and budget to be able to dive deep into this process and create a lasting impression for CSUN. I am always exploring how to celebrate the beauty and positivity of a community and their ways of life, but also how to not shy away from some of the hardships in their history. I feel this mural balances the two well, showing the true resilience, beauty and pride of the Tataviam throughout time.

What comes next?

In culmination of the mural, there will be two events hosted on campus. One is a mural reveal and celebration with the artist, supporting team of professors and tribal members, and FTBMI leadership. The second will be a Native Plant Walk where students will be invited to join myself and Tribal Senator Jesus Alvarez for a visit to the mural and a walk to the sustainability garden to visit native plants and learn about their significance to the Tataviam. Both events will be held during the Fall Semester at CSUN.

Give to the University Library

Give a Gift TodayThe annual distributions from the Louise Lewis Endowment for Tataviam Studies in honor of Mark Stover will support programs and exhibitions featuring speakers on the topic of American Indian Studies with special focus on the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, and that those speakers and topics be chosen by the Dean of the University Library in consultation with the Director of the University’s American Indian Studies Program and the leadership of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. The endowment may also provide funds for the purchase of reference materials (either print or digital) in American Indian Studies.