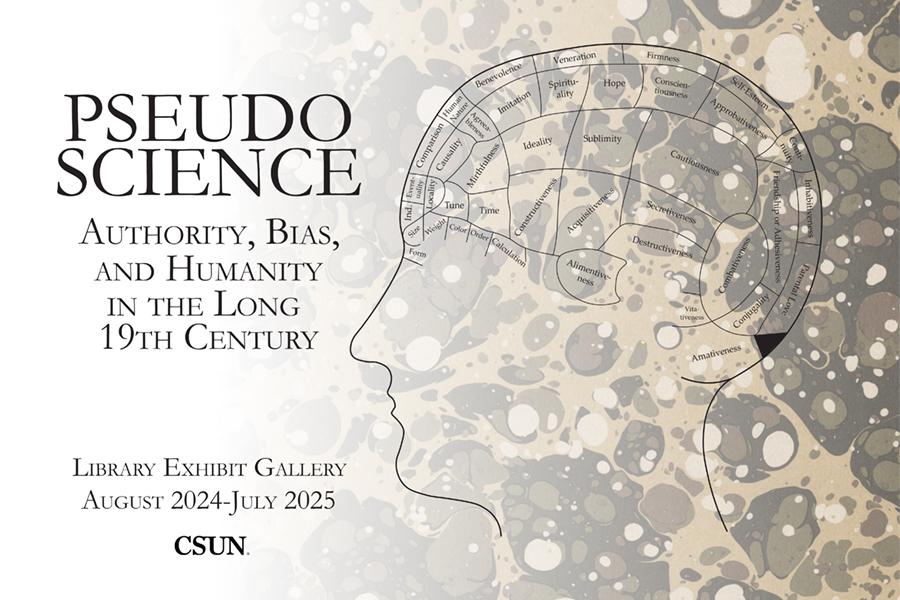

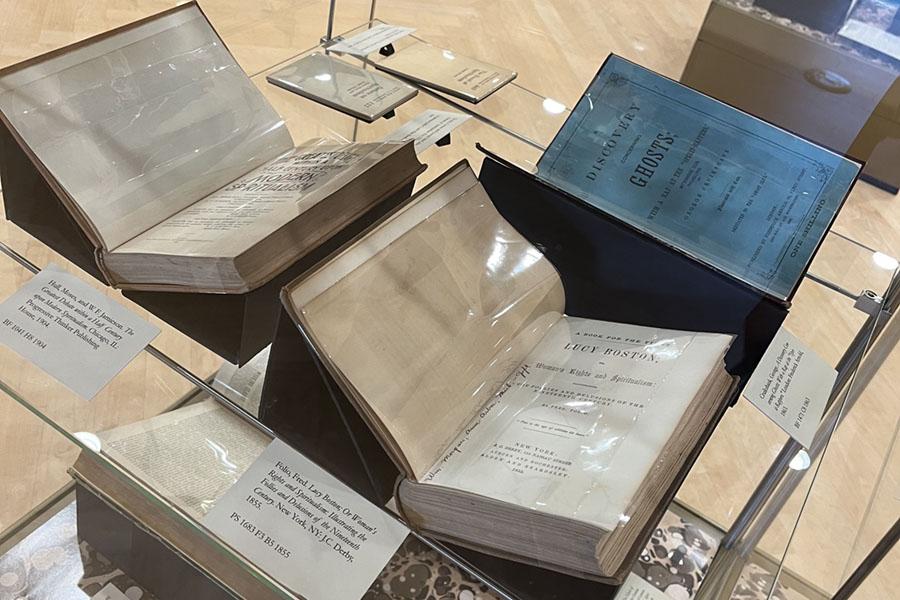

Pseudo- is a prefix meaning "fake" or "false," so the word "pseudoscience" immediately raises questions about scientific authority and the validity of the scientific method. Pseudoscience as a concept derives from the 20th century, when scientists, historians, and others worked to understand society's relationship to a series of scientific theories and beliefs newly understood as wrong-headed and harmful. It has been defined as any intellectual or technological pursuit that uses scientific methodology to "prove" a temporal or physical reality, but which in fact does not, as when someone uses a thermometer to detect ghosts.

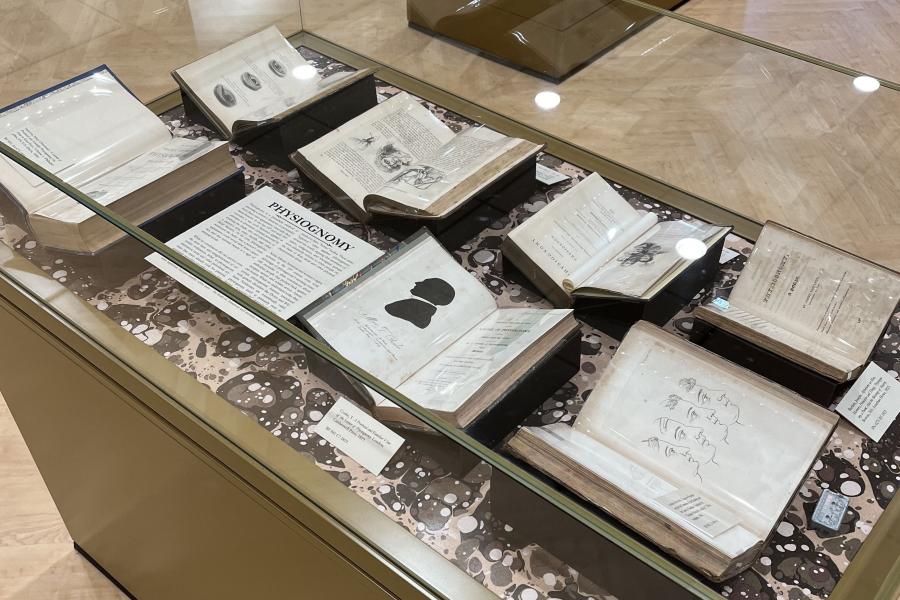

In the 19th century, as much of the world experienced rapid industrialization, scientists enthusiastically studied the world around them, crafting theories, running experiments, and inventing new technologies. While we still believe some are scientifically valid, like Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and germ theory, we understand others that initially appeared to be soundly researched, like physiognomy, mesmerism, phrenology, and eugenics, to be fraudulent quackery.

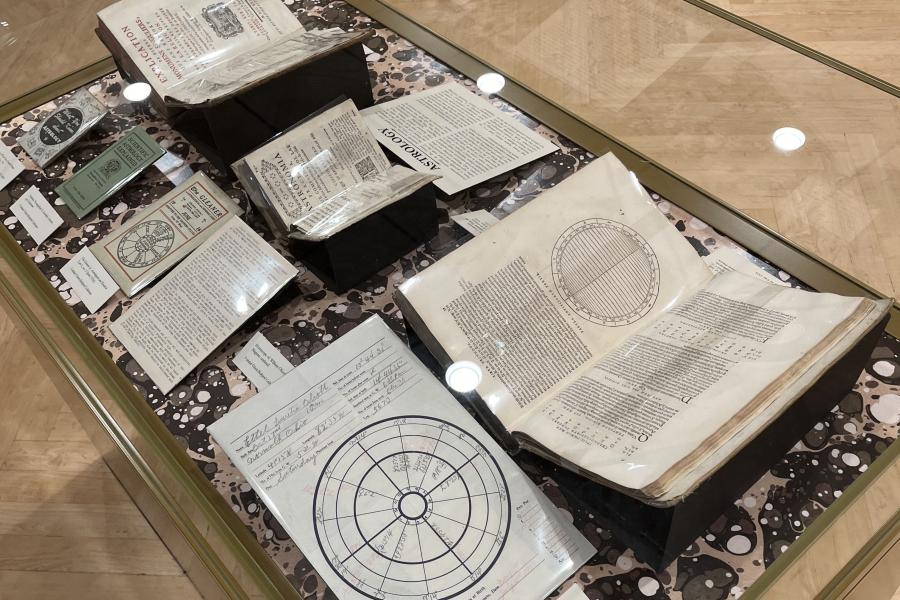

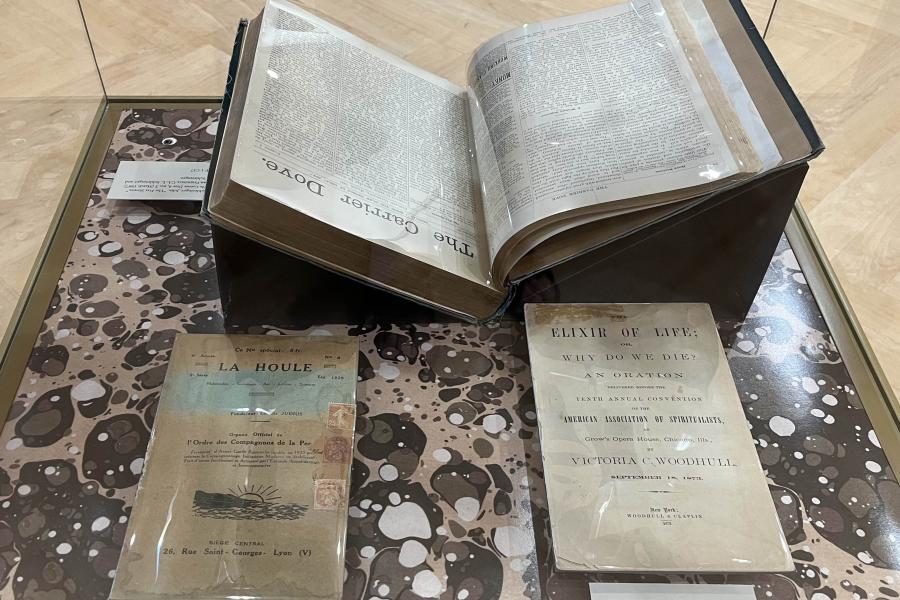

Studying pseudosciences can reveal how inherently human the practice of science is. Scientists' beliefs, interests, and identities shape their thoughts and focus their attention. The flood of scientific discovery and theory in the 19th century is evidence of a fundamental human desire to understand the world, but the theories themselves reflected the worldview of those in positions of power. Join us in considering a body of original texts and other resources from the long 19th century that document various pseudosciences as we engage with questions of scientific authority, the reliability of the scientific method, the relationship between early science and pseudoscience, and the degree to which historical context determines these labels, revealing the complex relationship between science and society over time.