Newsletter Edition: Fall 2023

Contributed by Elizabeth Altman

The latest exhibit from Special Collections & Archives, “Eating the Archives” opened in August 2023. The exhibit explores the way food-related archival materials “preserve community memories while reflecting and engaging with broader societal issues related to identity, representation, and daily lived experiences.” We spoke with the exhibit’s curator, Special Collections & Archives Librarian Mallory Furnier, about the rich array of documents, cookbooks, and ephemera that went into the exhibit, and the way they illuminate the role food plays in our lives.

What was the inspiration behind this exhibit?

Apart from being a fun topic, food is such a meaningful and well-documented aspect of culture that reviewing food-related archival materials gives us an opportunity to reflect on a range of fundamental social and historical components: family tradition, self-representation, history, cultural values, and economics. In the archives, we have an impressive number of cookbooks, particularly for the 20th century, as well as a Culinary Pamphlet Collection. In addition, food is such a broad topic that we were able to select materials from all six of our repository collecting areas, including over 60 different collections, as well as many publications from our book collection. Even the International Guitar Research Archives had materials relevant to the discussion of food! It’s something that everyone is forced to engage with to some degree or another, whether it’s a positive, a negative, or simply something we have to do to exist. So, everybody has a profound connection with food, even though our individual relationships with it can be very complicated.

What geographic and cultural scope does the exhibit cover?

Eating the Archives looks at American foodways, primarily from the late 19th through the 20th centuries. The term foodways encompasses what we eat, how we grow it, how we prepare it, and how it relates to our culture. Critical to a reflection on foodways is the means by which we establish and communicate our practices – formal cookbooks, periodical recipes, marketing souvenirs, family recipe cards and oral tradition. I tried to include as many different American perspectives as our gallery space allows, but of course there are many stories still left to be told! And since our archival collections preserve many artifacts of our own state’s cultural, economic and political past, this exhibit highlights a lot of Western American perspectives, with many items relating to California.

What does the exhibit tell us about how food has shaped California history?

This exhibit highlights the integral role California plays in our nation’s food supply. This is both from the general perspective of how we grow a lot of the nation’s foodstuffs, and also in the way California producers and consumers have alternately ignored and responded to the impact difficult working conditions and low wages have had on the people that work to grow, manufacture, and transport our food. The “Labor” case features items from the 20th century farm workers movements, including the 1965 Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee-organized Delano grape strike. The agricultural labor movement touched CSUN too – in 1970 the Associated Students urged a boycott of Valley State food services for using lettuce from Northern California farms exploiting lettuce workers. Food also substantially shaped California’s identity in the early 20th century boosterism period, when new housing developments used orange and avocado grove imagery to sell new suburban homes.

"Foodways and Identity" is one of the major themes of this exhibit. Can you talk a little bit about that?

The “Foodways and Identity” south wall case explores influential food factors that shape our knowledge of and relationship with food as Americans. Food is more than just a recipe – it is part of our fluid identities. It’s something we are taught, something we bring with us, and something that changes over time. Food influences how we see ourselves and those around us. And through our innovations and migrations, we make food as much as it makes us. How did an initial broad "American" food identity begin to emerge? What kind of institutional influences, often pressured into existence by concerned Americans, shape food regulation, food access, food contamination? Materials in the “Institutions” section ask us to consider consumer protection laws and the systemic economic forces that determine what we are actually able to access on an individual local level. Artifacts in the “Appliances and Sciences” section suggest how the technological advancements that enable us to have frozen food, or to cook food on new appliances, might inform our lifestyle and economic identities. Finally, American Foodways looks at ways that globalization and immigration expand American food horizons. All these elements create a palette we draw from to shape our own individual food palates.

Will we recognize any foodie personalities in this exhibit?

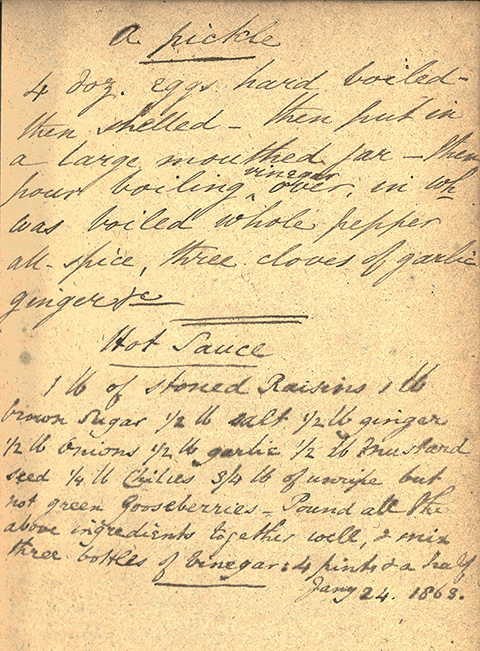

I focused less on specific influencers. Familiar names like Julia Child, Fannie Farmer, Betty Crocker, and James Beard do appear in the cookbook case, but I wanted to elevate the stories and recipes of non-famous individuals. You’ll see some of these in the recordings made by students in Bess Lomax Hawes’ CSUN folklore classes in the 1960s and 1970s, which preserve instances of oral transmission of food knowledge, as well as in the individuals named in handwritten recipes. Some of my favorite items in the exhibit are the handwritten recipes – some on recipe cards, others scrawled on scraps of reused paper. These recipes passed down for generations show us what was valued and worth recording and sharing. This exhibit focuses more on food’s appearance in our daily lives than on trending food.

How do you think Eating the Archives might be incorporated into CSUN instruction?

The exhibit showcases how many different material formats can contribute to a critical examination of specific food-related topics, as well as the importance of considering context and bias when evaluating information sources. The “Appropriation & Discrimination” case demonstrates that just because something was printed and widely distributed, doesn’t mean that it’s recording a lived truth. A Date with a Dish: A Cookbook of American Negro Recipes was written by Freda De Knight, a Black American, who spent twenty years collecting "over a thousand wonderful recipes from Negro sources." Her book centers the humanity and dignity of her food sources. In one example, she describes the recipes of Pauline, a daughter of caterers, and Charlie Saunders, a chef on a private rail car. This is in contrast to white author Patsie McRee's rhapsodizing about a mythical "Old South" in The Kitchen and the Cotton Patch through dehumanizing portrayals of her impressions of the enslaved Black people on her family's plantation. It’s important to look critically at who is telling a specific story, and what kind of contextual factors and motivators will influence that person’s perspectives.

What did you have to leave out of the exhibit and why?

There are some really fun photographs in the Richard Fish Collection from a shoot Fish did featuring craftspeople that create realistic-looking food art. The shoot included cast members from the 1970s television show Fantasy Island and was titled “Fantasy Food.” Fish also photographed vehicles shaped like a tomato and a cucumber, and I really wanted to get those in there! On a more serious note, if I had more space in the exhibit I would’ve liked to spend time exploring the impact of Japanese American farmers in the San Fernando Valley, as they played an important role in early 20th century Southern California farming. I would’ve also liked to more deeply explore the idea that progress isn’t linear. Plastic packaging and a transportation revolution allowed us to break produce free of seasons and have wide-ranging choices of pre-prepared foods in the freezer aisle, but many Americans are starting to look more closely at the ways our current food system is negatively impacting the environment.

Don’t forget to join us at the Opening Reception October 19!