Old China Hands Archives Newsletter, Volume 1, Number 1

November 13, 2020

From the Director

Welcome to the launch of our newly-reformulated newsletter.

I would like to begin by thanking the prime mover behind this effort, our dedicated archivist, Mallory Furnier, and hope that you will be interested in the stories she has put together.

In this period after the American national election of November 2020, in the midst of repeated national crises, including a pandemic which has so far killed more than 200,000 individuals, injured many more, and shows no signs of relenting, I am, as Director of the Old China Hands Archive and an Old China Hand in my own right, moved to remind readers of this newsletter that we can search for parallels between the stresses we are currently enduring and those experienced by many Old China Hands during their sojourns and careers in China.

Their lives were not simply unusual, but stressful, in ways similar and different from our own. I was born in Shanghai and came to California, with my family, as a boy of not quite fourteen. Since 1996, when I founded the Old China Hands Archive, I have met many other Old China Hands, in most cases older than I, and sadly, many of whom have passed away. Their stories, some of which we have collected through their donated materials and interviews, are highly varied, but share, I think a thread of overcoming hardships and stresses. They share the circumstance of moving to a host nation with a different culture and language, the necessity to adapt, to make a living, maintain their health, and raise children. This is a commonplace of immigrant and refugee status, but in the case of China, there were many singular nuances.

China’s host culture was an ancient and highly civilized one, but in most cases unfamiliar and not necessarily welcoming. The advent of Westerners and their civilization was, not infrequently, accomplished by force, resulting in the formation of enclaves such as the concession system, areas administered by foreign powers and deeply resented by the Chinese.

The foreigners who came to China in the approximate century from the mid-19th to the mid-20th, (and in some cases, such as the Portuguese, long before), were astonishingly varied in their backgrounds and aspirations. They spoke many languages, were of varied cultures and religions, and had to make their way in an often resentful China. Some learned the language, many did not, so English became an important all-purpose language among them. Some arrived with means, to trade and establish businesses. Some came with professions, such as the refugees from the revolutions, wars, pogroms and genocides of Europe, but were often destitute and had to start from great disadvantages. (Refugees from the Russian revolution and Jews escaping Nazi Europe often came with almost nothing.)

Everywhere, they had to engineer a coping mechanism for the world in which they found themselves. The China of my parents’ and grandparents’ generations, for all its fabulous monuments and history, was also the home of an often impoverished, politically-divided, disease-stricken, native population. The arrivals had to learn to communicate, manage financially in times of unstable currency and rampant inflation, avoid entanglements in civil and world wars, occupation and sometimes Internment by the invading Japanese, and maintain their health and that of their children. As I think back on my childhood in Shanghai, I realize that my parents spent much of their time worrying.

When it came to health, my family benefited from the fact that our dad was a pharmacist, but one protection that was largely absent was vaccination, except for smallpox. My sister and I experienced chickenpox, measles, rubella (German measles), and mumps; in my case, a dog bite which required multiple painful injections in my belly to defend against rabies—and there may have been other ailments which I cannot remember. We also had friends who endured whooping cough and scarlet fever. The antibiotic revolution did not begin till after World War II, although sulfa drugs were available. At home, all of our drinking water was boiled. Because local farmers fertilized their fields with night soil (collected daily in so-called “honey carts”), vegetables were either overcooked, or, in the rare cases when eaten raw, were first washed thoroughly in a potassium permanganate solution. Frequent hand-washing was the norm and there was an almost religious belief in the efficacy of soap. Interestingly, it may be that some of us children who survived in that dangerous environment developed immunities which protected us from common infections and allergies in later life.

Despite their problems, the Old China Hands expatriates often managed to achieve some prosperity, to establish educational institutions, commercial and recreational establishments, systems of laws and security in their concessions, and, most important of all, exchange cultural and technological benefits and drawbacks with the host country. Nonetheless, the daily pressure on them must have been unrelenting, culminating in the often-renewed assumption of refugee status when they were forced to leave, after the communists came to power in 1949, the China many had come to love.

Their new locations often presented yet another need to struggle and to survive for my parents’ generation. Those of us who were children then, with the resilience of children everywhere, took much of all this in stride, and settled successfully in our new homes, whether in the USA, Australia, Israel, in Latin America, or Europe. I was one of those, and I have come to feel a great sympathy, and respect, for the achievements and survival of the previous generations of Old China Hands. Our parents and grandparents left China in an agitated state and faced new stresses for the rest of their lives. All honor to them.

Robert Gohstand

November, 2020

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities. Each issue the Newsletter will feature collections from individuals representing a particular push or pull factor that led them to emigrate to China.

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities. Each issue the Newsletter will feature collections from individuals representing a particular push or pull factor that led them to emigrate to China.

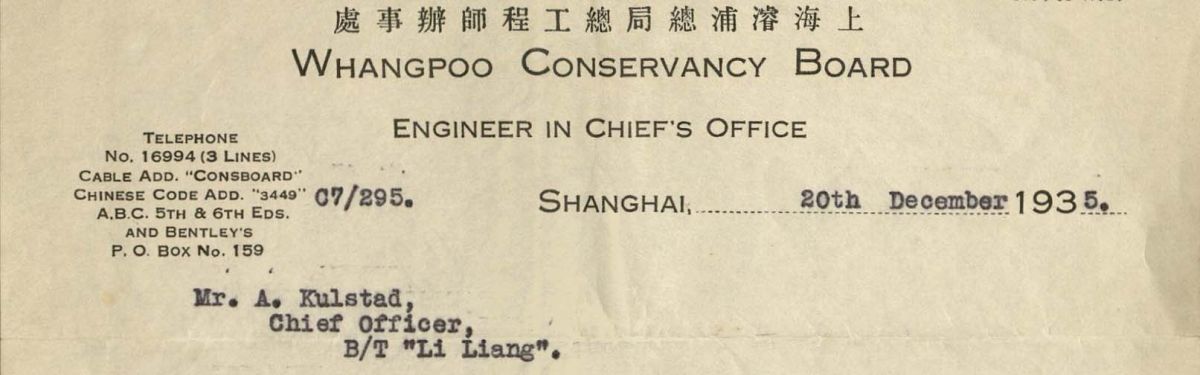

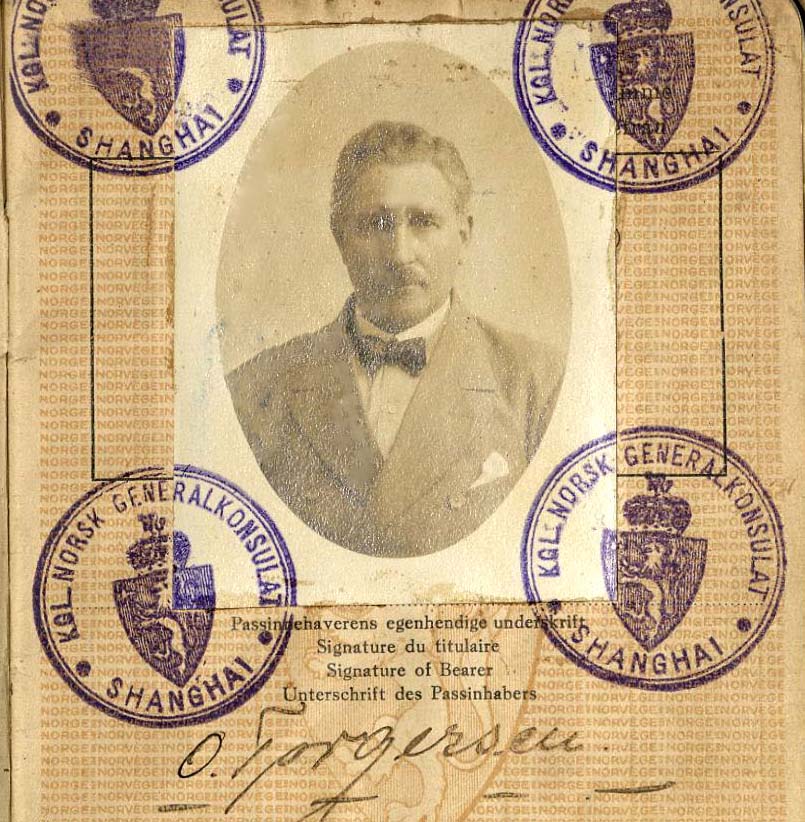

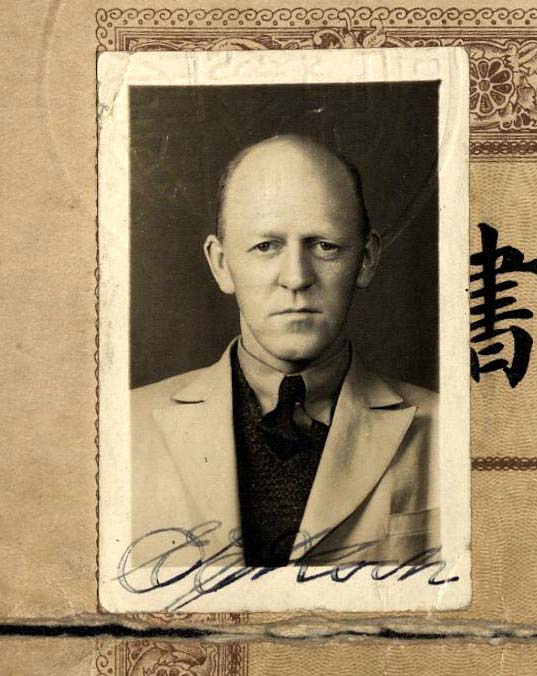

This semester's focus is on sea-based trade and shipping as a pull factor. The Peek in the Stacks blog post Early 20th Century Shipping in the Far East, features materials from the Erik J. Koch Collection documenting the life of Danish sea captain Koch who came to China in 1923, as well as the Olaf Torgersen Collection, which includes the records of Norwegian sea captain Torgersen. The finding aids for these collections, as well as the Captain Alv Kulstad and George Kulstad Collection documenting the work of Norwegian Peter Alv Kulstad, contain additional information about their seafaring careers and the archival materials in each of their collections:

This semester's focus is on sea-based trade and shipping as a pull factor. The Peek in the Stacks blog post Early 20th Century Shipping in the Far East, features materials from the Erik J. Koch Collection documenting the life of Danish sea captain Koch who came to China in 1923, as well as the Olaf Torgersen Collection, which includes the records of Norwegian sea captain Torgersen. The finding aids for these collections, as well as the Captain Alv Kulstad and George Kulstad Collection documenting the work of Norwegian Peter Alv Kulstad, contain additional information about their seafaring careers and the archival materials in each of their collections:

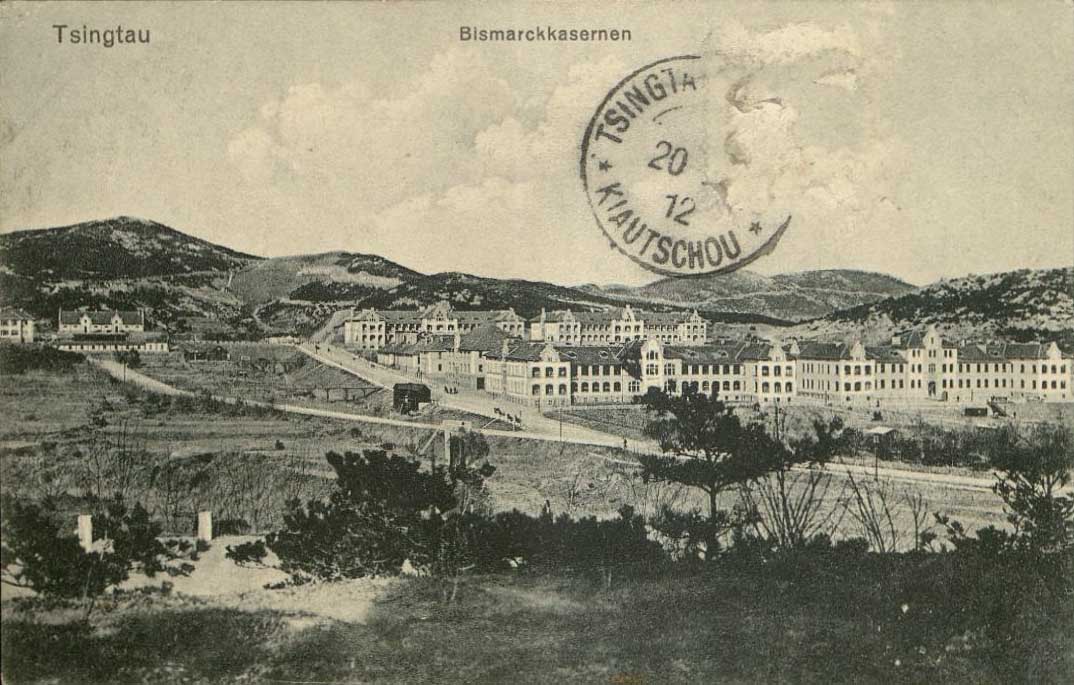

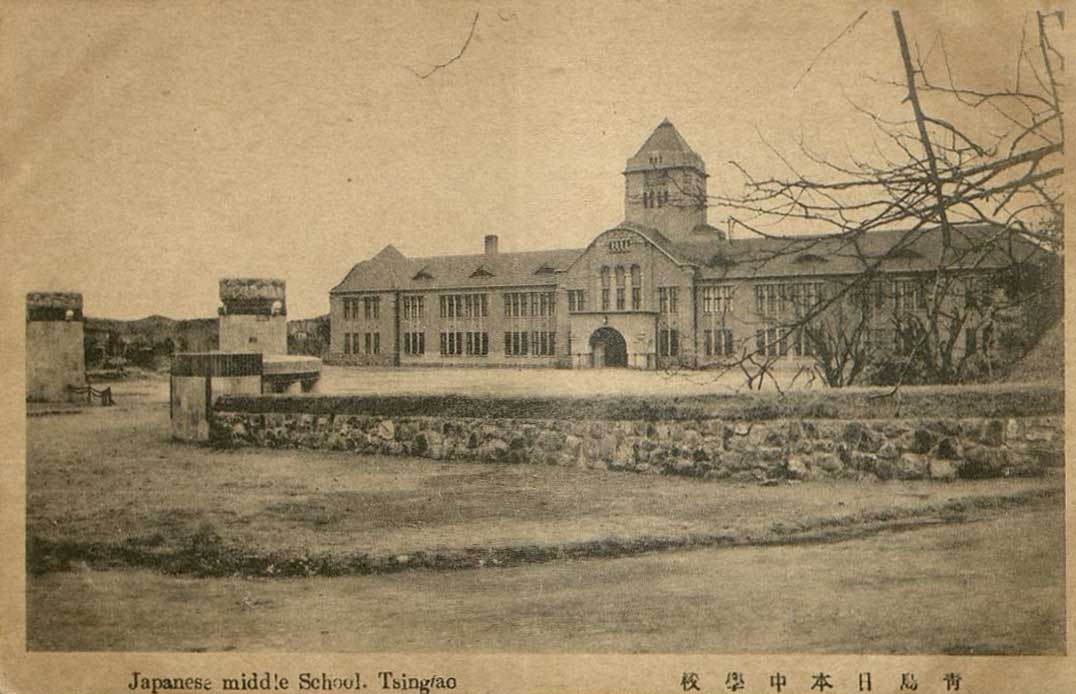

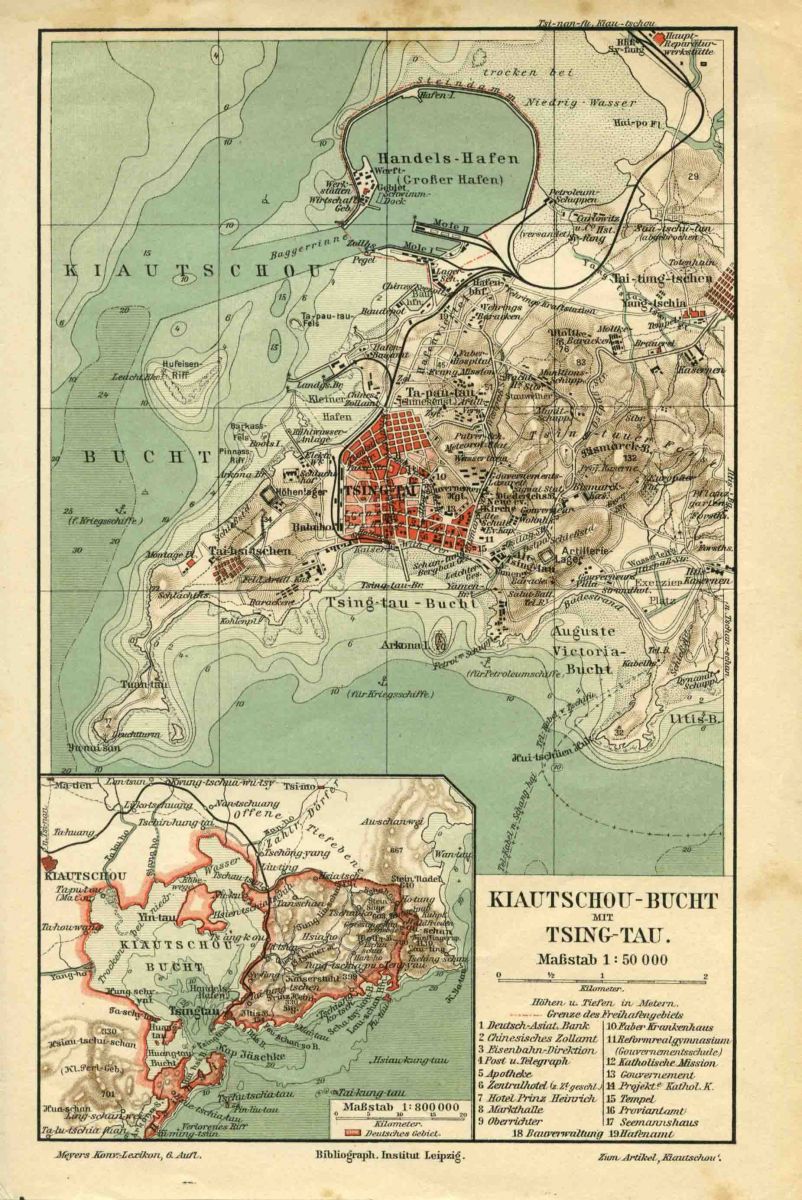

Tsingtao, now romanized as Qingdao, is a coastal city in northeastern China that was heavily influenced by German imperialism in the late 19th to early 20th century. In the 19th century imperialist European nations looked across the globe for other countries to colonize or exert spheres of influence over. Spheres of influence are regions that another state has exclusive cultural, economic, military, or political influence over. Prussia, and later Germany, had taken an interest in the area around Tsingtao as a possible naval base site. After the murder of two German Roman Catholic priests in 1897, German naval officials and troops moved to occupy Tsingtao and began negotiations with the Chinese government. The resulting Kiautschou Bay concession placed the city under German control following a lease agreement lasting from 1898 until 1914.

Tsingtao, now romanized as Qingdao, is a coastal city in northeastern China that was heavily influenced by German imperialism in the late 19th to early 20th century. In the 19th century imperialist European nations looked across the globe for other countries to colonize or exert spheres of influence over. Spheres of influence are regions that another state has exclusive cultural, economic, military, or political influence over. Prussia, and later Germany, had taken an interest in the area around Tsingtao as a possible naval base site. After the murder of two German Roman Catholic priests in 1897, German naval officials and troops moved to occupy Tsingtao and began negotiations with the Chinese government. The resulting Kiautschou Bay concession placed the city under German control following a lease agreement lasting from 1898 until 1914.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Japan issued an ultimatum to Germany to withdraw German warships from Chinese and Japanese waters and transfer control of the port of Tsingtao to Japan. When Germany did not comply, Japan declared war on Germany and placed the city under siege until German surrender two months later. After the end of the war, the city remained under Japanese control until 1922 when it came under control of the Republic of China, before once again coming under Japanese occupation from 1937 to 1945 during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Japan issued an ultimatum to Germany to withdraw German warships from Chinese and Japanese waters and transfer control of the port of Tsingtao to Japan. When Germany did not comply, Japan declared war on Germany and placed the city under siege until German surrender two months later. After the end of the war, the city remained under Japanese control until 1922 when it came under control of the Republic of China, before once again coming under Japanese occupation from 1937 to 1945 during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

After World War II Tsingtao was briefly the headquarters of the Western Pacific Fleet of the U.S. Navy before coming under control of the People's Republic of China in June 1949. Today it remains an important center of martitime trade as a modern port city and manufacturing center. The Tsingtao Brewery, founded by German settlers in 1903, remains a legacy of German occupation of the area, though operations are now owned by a number of private shareholders. Collections in the Old China Hands Archives that contain materials related to the German occupation period and the United States military presence include:

The Edward Gehrke Collection documents the military career of China Marine Edward Gehrke through photographs, ephemera, publications, and his military duffel, coat, and fatigues. Gehrke entered the U.S. Marine Corps in 1943 and served with Company 4th Marine Regiment, 1st Provisional Brigade at Guadalcanal, "A" Battery, 1st Battalion, 15th Marines, 6th Division as a gunner, and served as part of the Okinawa invasion landing on April 1, 1945. After he served in Okinawa, he was stationed in Tsingtao, China, where he was a participant in accepting the Japanese Army surrender in China.

The Edward Gehrke Collection documents the military career of China Marine Edward Gehrke through photographs, ephemera, publications, and his military duffel, coat, and fatigues. Gehrke entered the U.S. Marine Corps in 1943 and served with Company 4th Marine Regiment, 1st Provisional Brigade at Guadalcanal, "A" Battery, 1st Battalion, 15th Marines, 6th Division as a gunner, and served as part of the Okinawa invasion landing on April 1, 1945. After he served in Okinawa, he was stationed in Tsingtao, China, where he was a participant in accepting the Japanese Army surrender in China.

The Fred M. Greguras Papers include maps from the German imperial period pre-World War II, materials on the 6th Marine Division officers' club, souvenir handkerchiefs purchased by servicemen, and photographs and ephemera that document the China Marine presence throughout the region, with a particular focus on documenting the physical landscape and built environment as they change over time.

The Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection contains nearly 200 oral histories documenting a range of experiences. Interview topics include, but are not limited to, daily life in China, impressions of local culture and business, and experiences related to World War II such as the Japanese occupation and internment of Allied country citizens residing in China. Transcripts are available for most audio interviews. This issue we are featuring an interview conducted by the Old China Hands Archives at the Macau Cultural Center in Fremont, California in 2011 with Noele Brockman.

Noele Brockman was born December 25, 1927 in Shanghai, China to Portuguese and English parents. She attended Public Thomas Hanbury School for Girls in Shanghai and was a Girl Guide and member of Portuguese youth club Mocidade. Her father worked as an accountant and her mother as a secretary for Chase National Bank. After World War II she met and married her husband John George Brockman, an American solider stationed in China. The couple evacuated to the United States in 1948, ahead of the Communist establishment of the People's Republic of China. Her parents remained in China until 1952, when they reunited with Brockman in the United States.

On her mother and father's work and the family's social life:

"He was a CPA actually but I think they called him by a different name and he was always very good at math. Unfortunately I did not inherit that talent. (laughs) In school we had a lot of plays and musicals. Gilbert and Sullivan was one of my favorites. And we would exchange with other schools, perform at their school and they would perform at ours. And my parents had a very, very active social life. They belonged to the Lusitano Club which was the Portuguese club of the day and also they had other clubs where they worked for instance. My mother happened to work for the Chase National Bank...

And she worked there as a secretary for a long time until her boss was interned. But they had as I said a very active social life and most Europeans did. There were many night clubs, cabarets in those days, and every Saturday night the young people—I’m talking about the ‘30s now. So my parents were in their 30s and they would go to night clubs and dance all night and sleep all morning. I was not allowed to wake them before 11 o’clock and of course all the foreigners had servants. So it was very easy for the women to work. Now the wives of the now called CEOs and managers and directors and presidents and so forth, cause they didn’t have to work, so they did what socialites do nowadays—the same thing. But the—I wouldn’t say my parents were middle class exactly. They were upper middle class and most of the wives did work because they had servants to do all the menial work and when they had children each child had a nanny."

About her nanny, or amah:

"She came from the country as most amahs did. They come when they're young from the country and they trained in the general work like housemaid or a cook or an amah and mine was trained as an amah. And she apparently came to my mother when she was quite young, probably in her twenties. She stayed with us for almost twenty years and unfortunately during the war she got news that her family who were on a farm were suffering under the Japanese and she was very worried about them. So she asked my mother for permission to go back and see how they were and my mother said, "yes," and she left and never came back. And we never found out what happened to her. And we—I think she lived in Soochow, somewhere near Soochow. But it was on a little farm and nobody knew anything about her and of course it wasn’t possible to find out once the Japanese had control...

And the— my mother and her friends usually had the same type of amah. If they were not family members they were friends because it was sort of a network. When a new young about to be mother needed a nanny then she would ask one of her friends and the friend would tell her nanny to recommend somebody. So my mother really asked all her friends and their friends were asking us too about their nannies and amahs and unfortunately it was really a bad time because nobody knew what happened. And we’re really sorry because we would have helped her."

On her parents' departure from Shanghai in 1952:

"My father stayed for as long he could and then he finally decided that it wasn’t going to work and that the Chinese Communists did not want any foreigners...

They went—well I have to go back a little bit. When—after I got to the states, I was married in Shanghai in the Christ the King Church which is still open and standing. I was married in 1948 and we expected—my husband was in the service and we expected to be there for about three years, which is a normal tour for American soldiers. But suddenly we were given notice that we had to evacuate and evacuate meant going to the United States. So my husband and I left and of course my parents were left behind and I’m an only child and of course my mother thought she’d never see me again and she cried and cried and cried when I left. But I found out that as an American citizen I could send for my parents and Congress gave a special dispensation to war brides that instead of waiting approximately five years for citizenship like most other people did, they were granted two year stay. So at the end of two years I immediately applied for my citizenship and learned a lot of American history which I had not had in a British school. And I got my citizenship and immediately put in for my parents to come and they did. That’s why it took so long and when they left in ’40,’52, my—I had my citizenship because I got it in 1950. But the application to have them come over had not gone through yet so having to leave China, Shanghai they had to go someplace else and most people who left Shanghai at that time under those circumstances went either to Hong Kong or Tokyo...

And Tokyo was under American occupation so my parents felt that going to Tokyo might be better since they were hoping to come to the United States. So he was in Tokyo for a year and found a job there and as soon as the approval came in for them to come to the states he resigned from his job and they came over. And interestingly enough they came over on a ship cause planes weren’t so common then and only the very rich could fly. Most people traveled by steamer as they called them. And the first booking that he could get—he said when is the next boat to the U.S.? And they told him and he said I’ll take it. But he didn’t realize that it was going through the Panama Canal. So instead of arriving in San Francisco...it went all the way to New York."

The complete transcript, along with transcripts for other interviews conducted at the Macau Cultural Center in 2011, are available by request. Please contact the Old China Hands Archivist at mallory.furnier@csun.edu. The Old China Hands Archives also contain the John and Noele Brockman Collection, which contains a number of items collected by the Brockmans during their time in China. These include a jacket with hand-embroidered dragons, a sterling silver cigarette case with gold embossed dragons on the front, and a small sterling silver tray with a 1912 Chinese silver dollar embedded into the middle.

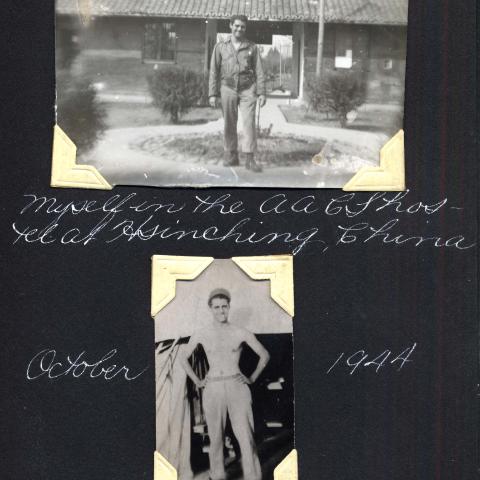

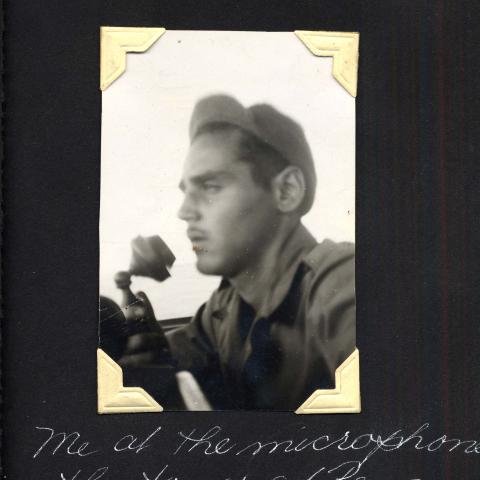

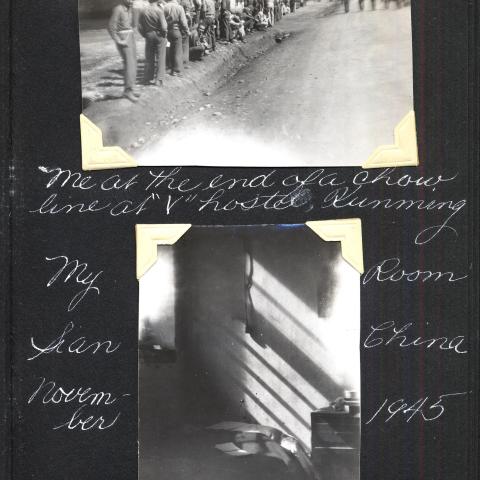

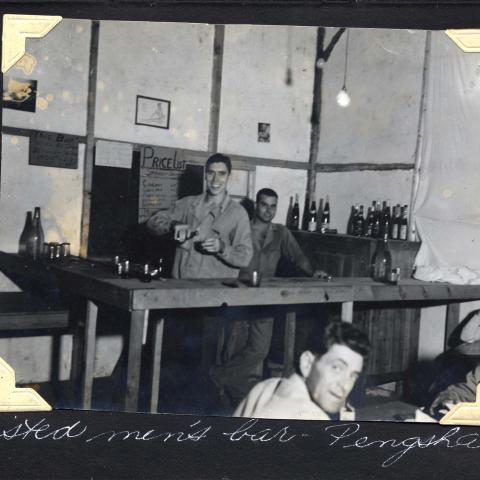

The Eliot and Hazel Wittenberg Collection documents Eliot Wittenberg's work as a control tower operator for the U.S. military in China at the close of World War II. The Collection includes a photograph album and souvenir embroidered handkerchief and fringed fabric items with dragon and floral designs. The photographs document Eliot Wittenberg's work for the United States Army Airways Communications System and were primarily taken in Pengshan and Sian, China. Several photographs were taken in Hsinching and Kunming. In addition to photographs of his time in China, there are also images of Bombay and Calcutta, India, the USS General J.R. Brooke, the Suez Canal, and Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. A selection of images from Eliot's photograph album are displayed in the gallery below:

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: old china hands archives, photographs, archives

Read more Old China Hands Newsletter blog entries