Old China Hands Archives Newsletter, Volume 1, Number 2

March 05, 2021

I sit down to write this brief letter at a moment in world history beset with tragedy. The Covid-19 pandemic continues to kill people around the world, even as the race to provide vaccinations against the disease continues. The United States has by now lost well over half a million people, leaving behind many more who mourn them. Refugees throng many parts of the world. The combat against encroachment on human rights and liberties and the dissemination of falsehoods, racist attitudes and conspiracy theories seems never-ending. China, the country of my birth, has made enormous strides in the nurturing of its population and is now an enormous economic powerhouse, but its technological advances are accompanied by restrictions on human rights, be it in Hong Kong, Sinkiang (Xinjiang), Tibet, or in the monitoring of individual behavior and dissemination of information.

I sit down to write this brief letter at a moment in world history beset with tragedy. The Covid-19 pandemic continues to kill people around the world, even as the race to provide vaccinations against the disease continues. The United States has by now lost well over half a million people, leaving behind many more who mourn them. Refugees throng many parts of the world. The combat against encroachment on human rights and liberties and the dissemination of falsehoods, racist attitudes and conspiracy theories seems never-ending. China, the country of my birth, has made enormous strides in the nurturing of its population and is now an enormous economic powerhouse, but its technological advances are accompanied by restrictions on human rights, be it in Hong Kong, Sinkiang (Xinjiang), Tibet, or in the monitoring of individual behavior and dissemination of information.

The world which we Old China Hands inhabited now seems very long ago and very far away. It too was a harsh world. That was a China in the throes of colonialist encroachment and civil strife, as well as the cruel invasion by Japan. Old China Hands had to, somehow, survive in the midst of that turmoil, and the Archive serves to remind us of the conditions prevalent at the time. Through an accident of birth and longevity, I find myself one of the final cohort of those who have personal memories of those days.

So, perhaps it is appropriate that the articles in this issue are all related to people with whom I had a personal relationship, whether they be relatives or friends. I cherish their memory and sadly miss them all.

Robert Gohstand

March 23, 2021

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities. Each issue the Newsletter will feature collections from individuals representing a particular push or pull factor that led them to emigrate to China.

Leading up to and during World War II, increasing anti-semitism and persecution of Jewish communities in Europe pushed many Jewish individuals and families to seek refuge elsewhere. Many ended up migrating to China; particularly Shanghai, which became known informally as the "Port of Last Resort."

Leading up to and during World War II, increasing anti-semitism and persecution of Jewish communities in Europe pushed many Jewish individuals and families to seek refuge elsewhere. Many ended up migrating to China; particularly Shanghai, which became known informally as the "Port of Last Resort."

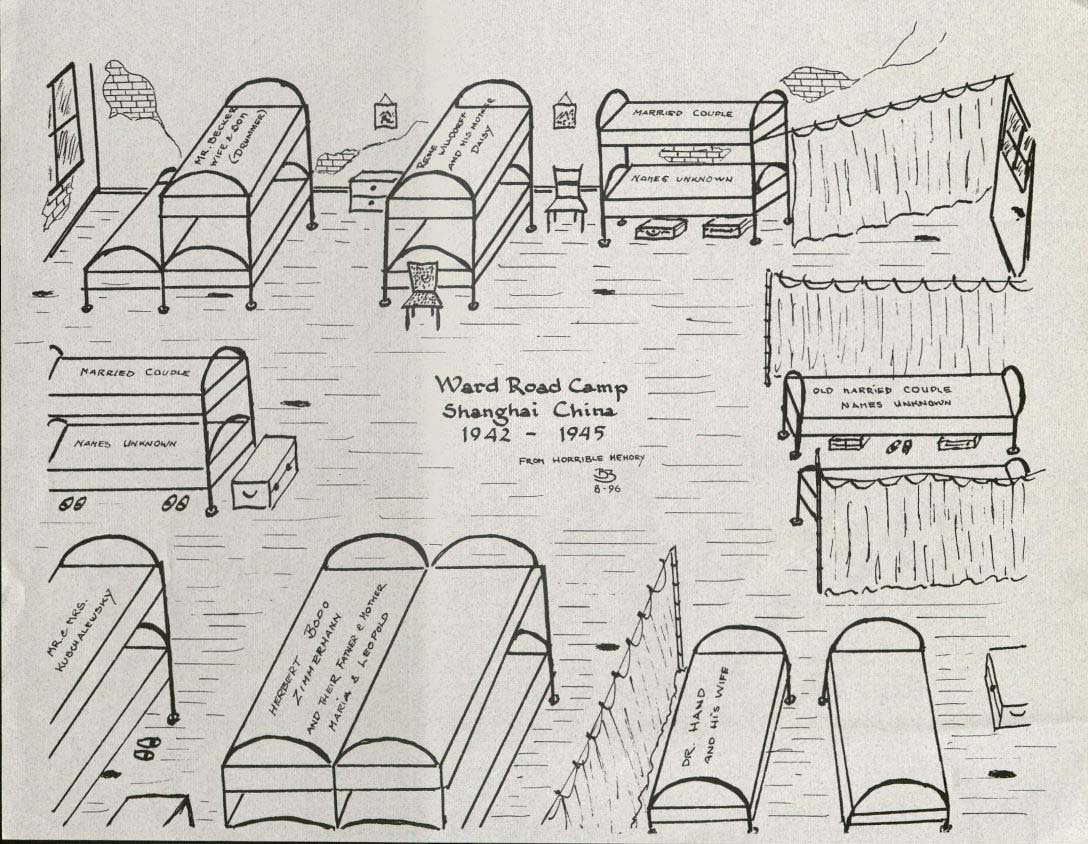

The Peek in the Stacks blog post Jewish Experiences in China during World War II, features materials that preserve the experiences of Jewish families that moved to China to escape persecution in Europe around the time of World War II. The Bodo Zimmermann Papers document Zimmermann and his family's lived experience as they left Berlin, Germany for Shanghai in 1940 after their home and business were confiscated by Nazi officials. The blog also highlights the Hanni Sondheimer Vogelweid Collection. Her family initially moved from Germany to Estonia for business, and later settled in Kaunas, Lithuania. At the start of World War II, the family began to look for a way out of Lithuania to escape rising anti-semitism in Eastern Europe.

The finding aids for these two collections, as well as several others documenting the experiences of Jewish refugees from Europe during and directly preceding World War II, contain additional information about their lives and the archival materials preserved in each of their collections:

- Bodo Zimmermann Papers

- Hanni Sondheimer Vogelweid Collection

- Sylvia Maehrischel Collection

- Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection (select interviews)

- Frank and Trixie Wachsner Collection

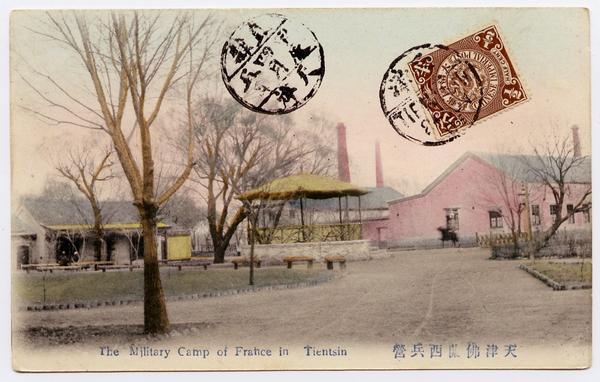

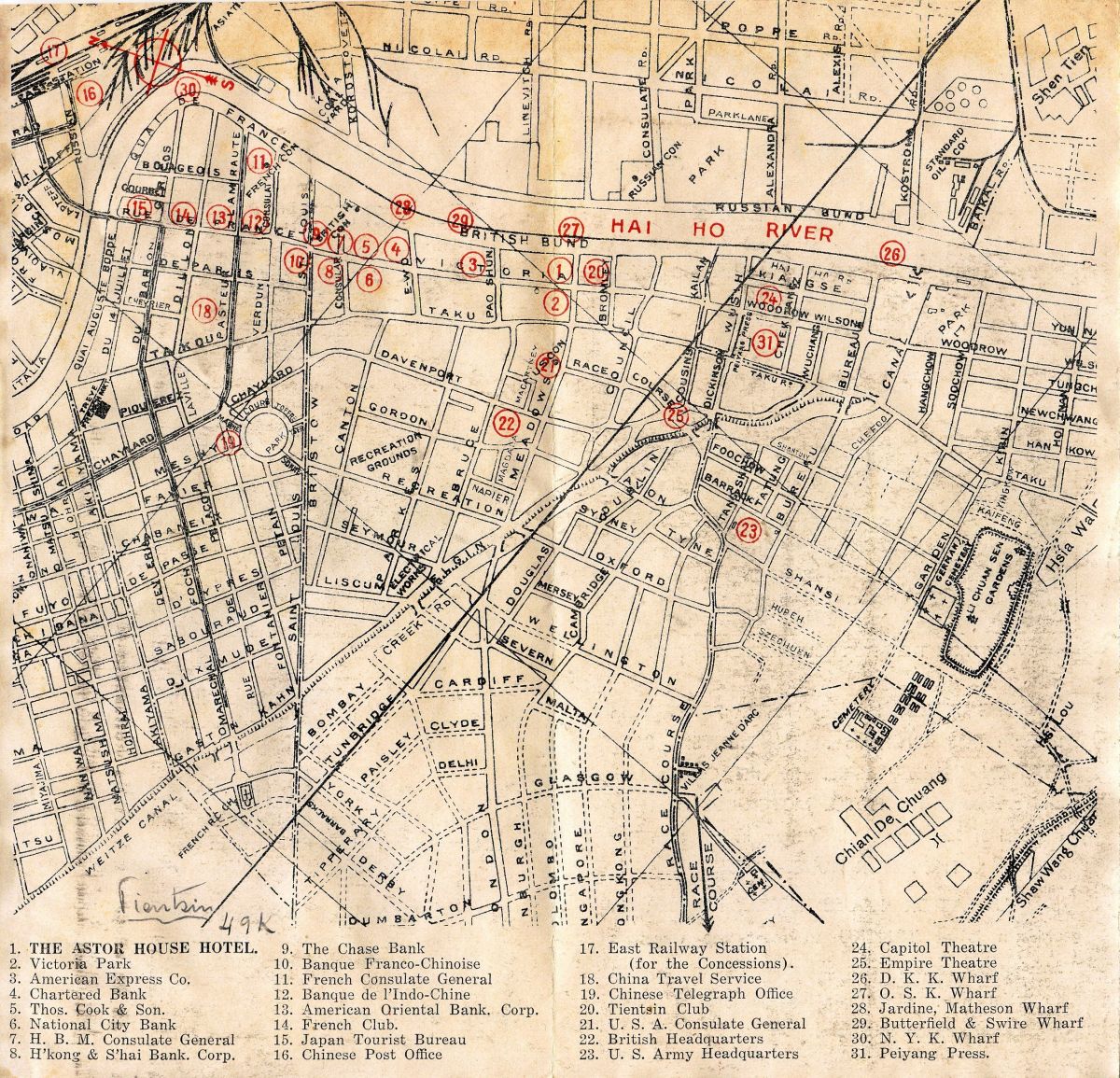

Much like Tsingtao, the incursion of foreigners into Tientsin began with treaties that segmented the city into a number of domains of influence. Beginning in 1860 the Qing dynasty ceded control of parts of the city to European countries, the United States, and Japan as concession territories. These areas remained concession territories until World War II when Japan gained control of most of the concession areas with the occupation of the American and British concessions. Prior to World War II, Japan began occupation of Tientsin in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Much like Tsingtao, the incursion of foreigners into Tientsin began with treaties that segmented the city into a number of domains of influence. Beginning in 1860 the Qing dynasty ceded control of parts of the city to European countries, the United States, and Japan as concession territories. These areas remained concession territories until World War II when Japan gained control of most of the concession areas with the occupation of the American and British concessions. Prior to World War II, Japan began occupation of Tientsin in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

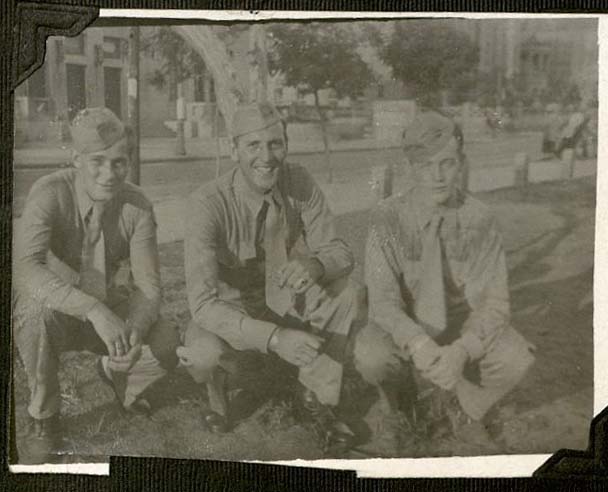

At the close of World War II United States Marines, primarily from the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, were deployed to North China. Tientsin was the site of surrender of Japanese troops in China to the United States Marine Corps on October 15, 1945. Collections in the Old China Hands Archives document this from the perspective of American military personnel working in the region at the time. U.S. Marines remained in North China for several years following World War II, departing in June 1949.

The Charles McHaney China Marines Photograph Collection documents McHaney's service as a U.S. Marine stationed in Tientsin, China during and after World War II. While in Tientsin, he took numerous photographs, the subjects of which are primarily his fellow Marines, local geography, and local culture. The collection consists primarily of these photographs, with some additional print materials related to the U.S. Marine presence in Tientsin in the late 1940s.

The Charles McHaney China Marines Photograph Collection documents McHaney's service as a U.S. Marine stationed in Tientsin, China during and after World War II. While in Tientsin, he took numerous photographs, the subjects of which are primarily his fellow Marines, local geography, and local culture. The collection consists primarily of these photographs, with some additional print materials related to the U.S. Marine presence in Tientsin in the late 1940s.

Faces of Tientsin in our Digital Collections includes photographs taken by Harold Giedt in Tientsin in 1946. Harold Giedt, the child of American missionary parents, was born and raised in Shanghai where he attended the Shanghai American School. He returned to China in 1945 as a newly-commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Having received training from the military in Mandarin Chinese, he was posted to an assignment in Civil Affairs in Tientsin. He was an enthusiastic amateur photographer, and, before leaving for China, acquired a Kodak Bantam 828 camera for colored slides and a twin lens reflex for black and white photography.

Faces of Tientsin in our Digital Collections includes photographs taken by Harold Giedt in Tientsin in 1946. Harold Giedt, the child of American missionary parents, was born and raised in Shanghai where he attended the Shanghai American School. He returned to China in 1945 as a newly-commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Having received training from the military in Mandarin Chinese, he was posted to an assignment in Civil Affairs in Tientsin. He was an enthusiastic amateur photographer, and, before leaving for China, acquired a Kodak Bantam 828 camera for colored slides and a twin lens reflex for black and white photography.

The Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection contains nearly 200 oral histories documenting a range of experiences. Interview topics include, but are not limited to, daily life in China, impressions of local culture and business, and experiences related to World War II such as the Japanese occupation and internment of Allied country citizens residing in China. Transcripts are available for most audio interviews. This issue we are featuring an interview with Liliane Ransom conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1996.

Liliane (Heimendinger) Ransom was born in Shanghai, China on September 3, 1928 to Blanche Haenel and Julien Heimendinger. Her father Julien was born in Alsace-Lorraine, France and initially came to Shanghai in 1908 to apprentice in his uncle's jewelry business, and later ran his own car dealership selling Fiat, Renault, and Citroen automobiles. Ransom attended Shanghai Public School for Girls and lived in the Washington Apartment on Avenue Petain in the French Concession. She met her American husband Richard Ransom while he was working for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in Shanghai. After World War II, Ransom's parents and sister Arlette returned to France, while Ransom and her husband left Shanghai for New York City in February 1949. After leaving China, they lived in France, Germany, and Pakistan before returning to the United States and eventually settling in California.

Liliane (Heimendinger) Ransom was born in Shanghai, China on September 3, 1928 to Blanche Haenel and Julien Heimendinger. Her father Julien was born in Alsace-Lorraine, France and initially came to Shanghai in 1908 to apprentice in his uncle's jewelry business, and later ran his own car dealership selling Fiat, Renault, and Citroen automobiles. Ransom attended Shanghai Public School for Girls and lived in the Washington Apartment on Avenue Petain in the French Concession. She met her American husband Richard Ransom while he was working for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in Shanghai. After World War II, Ransom's parents and sister Arlette returned to France, while Ransom and her husband left Shanghai for New York City in February 1949. After leaving China, they lived in France, Germany, and Pakistan before returning to the United States and eventually settling in California.

On why her father went to China:

"...he came from a family with twelve children, and they lived on a farm in Alsace-Lorraine, and in those days it was very, very hard you know, people had to help each other. And so when the kids became like sixteen or eighteen years old, when they were through with school they would send these children wherever they had relatives—to America or wherever—and they had an uncle who was in Shanghai, he was in business, they were, jewelry business. They made watches and things like that. So they sent my father there as an apprentice, and so that my father could work there and send some money back home."

On her childhood in China:

"I was born in 1928, as I said. I lived there for 20 years. I went to school there, Shanghai Public School for Girls, and we lived on Avenue Petain. My whole life I lived in the same place, went to the same school. We were French so we were not interned."

On spending time with the family's Chinese servants:

"Well, I loved being with the Chinese servants. In fact when my parents, who would go out a lot, they were very social and there were lots of cocktail parties and all that—my best fun was staying home with the servants. I mean I practically felt the amah was my mother, I mean, you know because I was with her so much. And lots of people say that I have a very patient, quiet nature, and that they think that I’m, you know have wisdom and all that and I would say that I really learned a lot of it from the Chinese servants. I’d play Mahjong with them, and my parents would never let me in the kitchen, they said that’s the servants quarters and all, but as soon as my parents left we’d run into the servants quarters, we’d eat their food, and—one of the funny things was my parents never let them use our bathrooms, and our bathtubs you know. Well I was in the kitchen with them playing Mahjong, and gambling, and eating their food—which was probably much healthier than ours because even though they had very poor food, we had all this fat food you know and we didn’t realize it. Oh they would go in our bathtub, and mum was the word you know. We had, we, the kids had a great time."

Sharing final interview thoughts on China:

"I just say it’s my happiest time. Whenever I have a blue period, or whenever, say I’m at the dentist and he says think of something happy, you know, I always think of China. And I encourage everybody to start writing their stories, because you know as I write in my computer I, I can’t think of all these things right now to tell you but I live every moment over again, you know. And I’m sitting there at the computer sometimes I’m just crying. Sometimes I’m having visits with my parents, we had such a happy life, my parents. And I was so well adjusted, I had such a happy childhood. I sit and think about that, I’m in another world. So even if you don’t want to publish anything, I think I would tell everybody, do sit down and write your story, even if you’re not a good writer."

The complete transcript, along with transcripts for other interviews conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas in 1996, are available by request. Please contact the Old China Hands Archivist at mallory.furnier@csun.edu. Select oral history transcripts and audio from the Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection are currently available online on Digital Collections, with additional interviews to be added soon.

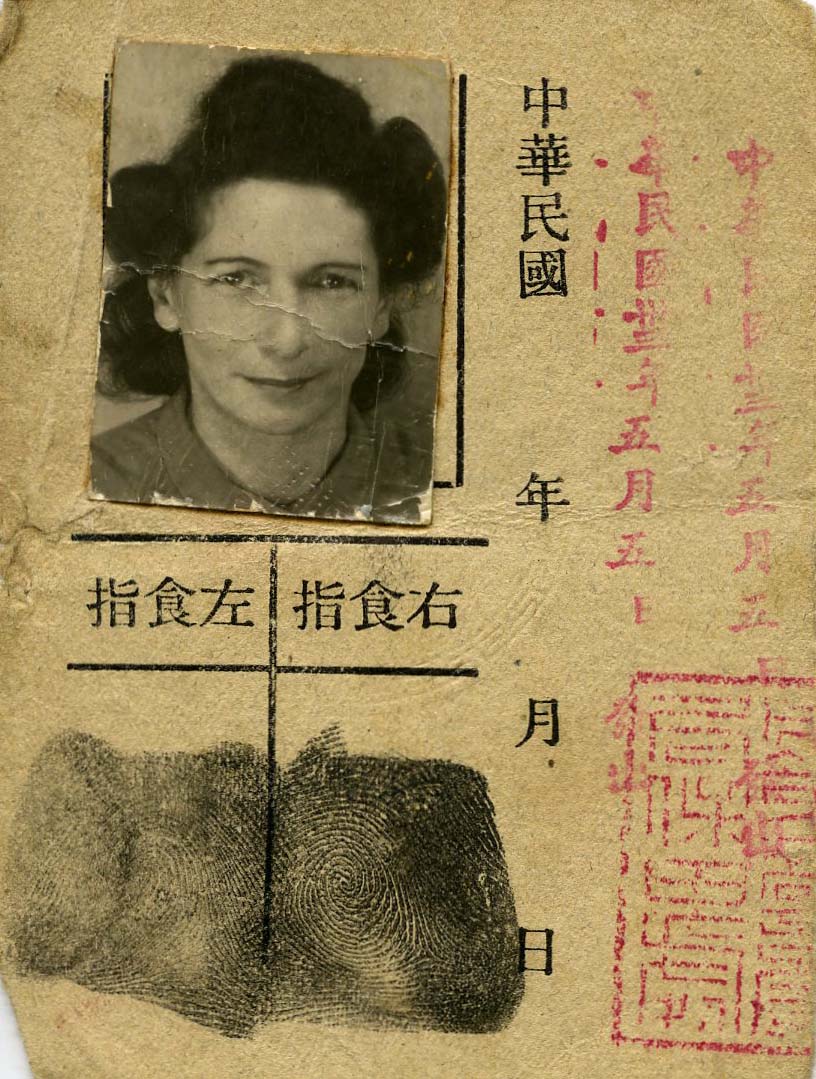

The Muzza Eaton Collection documents the lives of Muzza Rosenstein and her Russian emigrant family in Harbin, Dairen, and Shanghai, China before they moved to the United States after World War II. The Collection contains family photographs, correspondence, school records from Public and Thomas Hanbury School for Girls and Shanghai Jewish School, Belmont Apartments rental records, business records, and vaccination and immigration records. The family first moved from Russia to Harbin, and later lived in Dairen and Shanghai. Most of the collection relates to the Rosenstein family's daily life and work in Shanghai before they immigrated to the United States.

The Muzza Eaton Collection documents the lives of Muzza Rosenstein and her Russian emigrant family in Harbin, Dairen, and Shanghai, China before they moved to the United States after World War II. The Collection contains family photographs, correspondence, school records from Public and Thomas Hanbury School for Girls and Shanghai Jewish School, Belmont Apartments rental records, business records, and vaccination and immigration records. The family first moved from Russia to Harbin, and later lived in Dairen and Shanghai. Most of the collection relates to the Rosenstein family's daily life and work in Shanghai before they immigrated to the United States.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: old china hands archives, photographs, archives

Read more Old China Hands Newsletter blog entries