Old China Hands Archives Newsletter, Volume 2, Number 1

November 05, 2021

From the Director: Some Memories of Shanghai Christmases

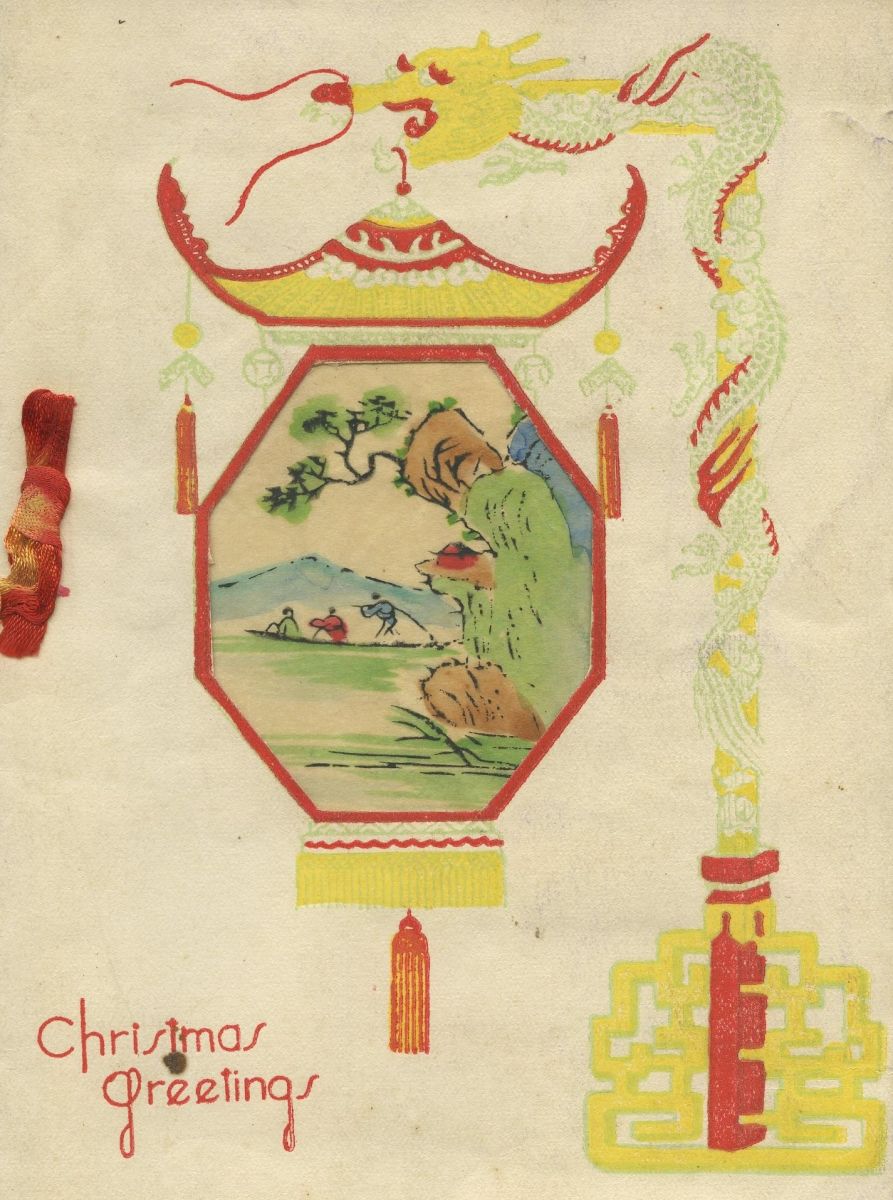

To Old China Hands, living as they did so far from their original homes, the traditional holidays were very important and enthusiastically celebrated. Furthermore, the cosmopolitan environment of Shanghai encouraged observance of some holidays which could be considered universal. Christmas was one such.

To Old China Hands, living as they did so far from their original homes, the traditional holidays were very important and enthusiastically celebrated. Furthermore, the cosmopolitan environment of Shanghai encouraged observance of some holidays which could be considered universal. Christmas was one such.

I was about thirteen and a half years old when my family and I boarded the General M. C. Meigs to sail to San Francisco, but some memories of events and holidays have lingered. My father was the proprietor of St. George’s Pharmacy at 1599 Bubbling Well Road in the International Settlement. That section of the road, running between Hart Road and the St. George’s tramway terminus, was particularly interesting and lively. Along the way was a large cemetery for foreigners, while beyond that, if memory serves, was the Bubbling Well itself—a large square enclosure with a low wall and malodorous water at the bottom. It was a popular gathering and street-vending spot. Just opposite was the entrance to the Bubbling Well Temple, always crowded with worshipers and the air of which carried the unforgettable scent of joss sticks.

But these were fixed elements of our neighborhood. Our block was also the site of two particularly well-known periodic markets or fairs.There was the basket fair, where the sidewalks were crowded with vendors of every possible woven thing: baskets of all types and sizes, but also rattan furniture and the like. People came to buy from far and wide and there were plenty of vendors of all kinds of food and tucks (snacks). It was noisy, crowded, and exciting.

The second market fair of the year was of Christmas trees. My family always celebrated this holiday, with guests, food, gifts, and a decorated tree. And some time before the holiday, our street was magically chock-a-block with Christmas trees, seemingly of every size and species. The piney scent was delightful, and my elder sister and I were in charge of roaming up and down the block in search of the perfect tree, which, once found and purchased was dragged through the pharmacy door and up the stairs to the living quarters over the store.

In preparation for the holiday, my father would also make and stock items for people to buy as gifts. One very popular item we helped our dad make was bath salts, tinted in various colors and put up in fancy glass jars. The stock of cosmetics and perfumes was also enlarged. I still remember one popular brand of perfume: Soir de Paris, or Evening in Paris. For men, there was 4711 cologne, after-shave and assortments of shaving soaps, mugs, and brushes. 4711, pronounced four-seven-eleven, is a venerable product, the original "cologne," invented by monks of that city before the Napoleonic era and drawing its name from the monastery’s address. It is still available, as beautifully labelled as 75 years ago, through Amazon. Soir de Paris, which, I am informed, was launched in 1928, in its distinctive midnight blue packaging, also still exists, but Amazon now wants $106 for 1.7 ounces! I’m sure that it was cheaper in the 1940s! The pharmacy’s front windows would also be redecorated with a holiday theme, put together by a professional window dresser (yes, that used to be a profession—is it still? Perhaps.)

The Old China Hands Archives wishes all the readers of our newsletter a safe and kindly Thanksgiving and Happy Christmas and Hannukah.

Robert Gohstand

November 2021

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities. There were a number of push and pull factors that caused Russian families and individuals to migrate China, especially northern China.

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities. There were a number of push and pull factors that caused Russian families and individuals to migrate China, especially northern China.

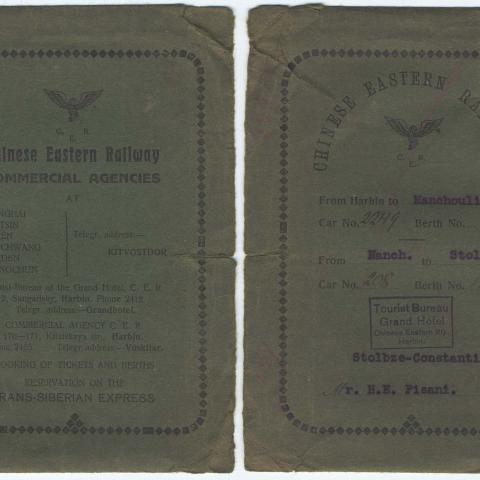

After Sino-Japanese war of 1895 Tsarist Russia obtained a concession to build the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) across Manchuria to link the Trans-Siberian Railway to the eastern port Vladivostok. Russia claimed extraterritorial rights for the railway zone, creating a swath of land in China that was outside of local jurisdiction and largely under Russian control. Along with the business opportunities presented by the railway, greater tolerance for the Jewish community in the extraterritorial zone made emigration to northern China appealing.

After Sino-Japanese war of 1895 Tsarist Russia obtained a concession to build the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) across Manchuria to link the Trans-Siberian Railway to the eastern port Vladivostok. Russia claimed extraterritorial rights for the railway zone, creating a swath of land in China that was outside of local jurisdiction and largely under Russian control. Along with the business opportunities presented by the railway, greater tolerance for the Jewish community in the extraterritorial zone made emigration to northern China appealing.

Then in 1917 the regime change and civil war sparked by the Russian Revolution led many refugees to initially move to Manchuria and other locations in China. Those that opposed the victorious Bolshevik Reds were known as "Whites," and were comprised of both tsarist supporters and a variety of other ideological groups in opposition to the Soviets. In 1921 the Soviet government revoked citizenship of all political exiles, making many Russians in China stateless.

This Peek in the Stacks blog post features the Dr. Tatiana Belitsky Collection. Dr. Belitsky was born in 1906 in Samara, Russia, but attended dental school in Harbin, China. She worked in Shanghai as a dental surgeon from the early 1930s until 1949. Several other collections also document the experiences of Russian emigre families in China, including:

This Peek in the Stacks blog post features the Dr. Tatiana Belitsky Collection. Dr. Belitsky was born in 1906 in Samara, Russia, but attended dental school in Harbin, China. She worked in Shanghai as a dental surgeon from the early 1930s until 1949. Several other collections also document the experiences of Russian emigre families in China, including:

Beijing, often referred to as Peking in the Old China Hands Archives, has a long history of foreign residents. Jesuit missions first reached Beijing at turn of the 16th century.

Beijing, often referred to as Peking in the Old China Hands Archives, has a long history of foreign residents. Jesuit missions first reached Beijing at turn of the 16th century.

The Second Opium War concluded in 1860 with British and French troops entering the Forbidden City in Beijing, and China signing the Convention of Peking with the belligerent countries and Russia. The Convention of Peking required the Qing Dynasty to allow foreign countries' diplomats to reside in Beijing. The British, French, and Russian legations were established in 1861, followed by an American legation in 1862, and several other countries over the following decades. The area occupied by these foreigners became known as the Legation Quarter.

By the time of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Legation Quarter was occupied by eleven nations' legations. The Boxers were an anti-foreign, anti-Christian, and anti-imperialist group that aimed to drive the foreigners out of China. An Eight-Nation Alliance of foreign troops defeated the Boxers, leading to the signing of the Boxer Protocol which established Legation Quarter boundaries and solidified foreign control of the area. Although most of the buildings in the Legation Quarter were damaged or destroyed during the Rebellion, the area was rebuilt and now also patrolled by foreign soldiers.

In 1928 the capital of China moved to Nanjing, but the legations remained in Beijing. During World War II when the Japanese army invaded and occupied the city, many foreign residents left the Legation Quarter. Those that remained were interned at the Weihsien Interment Camp until the end of the war. Several legations remained in Beijing after Chinese nationalist forces surrendered to the Communists in 1949.

In 1928 the capital of China moved to Nanjing, but the legations remained in Beijing. During World War II when the Japanese army invaded and occupied the city, many foreign residents left the Legation Quarter. Those that remained were interned at the Weihsien Interment Camp until the end of the war. Several legations remained in Beijing after Chinese nationalist forces surrendered to the Communists in 1949.

The Bill Mochon China Marines Photograph Collection reflects Mochon's interest in photography and U.S. Marines history through a collection of twenty photographic prints made from the original negatives collected by Mochon. The photographs primarily depict U.S. Marines in the Legation Quarter area in Beijing.

The Robert and Eva Tharp Collection documents their missionary work in China and India. Evangeline (Eva) Kok was born in 1914 in Yunnan, China, to Dutch missionary parents. In 1918, her family moved to Beijing, where her father served as the First Chancellor of the Netherlands Legation in China. Eva attended the Peking American School, graduating in 1931.

The Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection contains nearly 200 oral histories documenting a range of experiences. Interview topics include, but are not limited to, daily life in China, impressions of local culture and business, and experiences related to World War II such as the Japanese occupation and internment of Allied country citizens residing in China. Transcripts are available for most audio interviews. This issue we are featuring an interview with Allie Sanborn conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1996.

Allie Marie Sanborn was born in Shanghai on July 25, 1930. Her father father James Gordon Sanborn moved to China to work as a milling engineer and met and married Allie's Chinese mother, Allie Marie Daugh. Her family initially lived in the French Concession before moving out to a newly built house on Hung Jao Road. She attended Asbury Academy and then the Public School for Girls. The family moved temporarily back into town after the Japanese occupation began, then back to the country, and then to an apartment at the mill where her father worked. They were later interned with her father and brother at Chapei Civilian Assembly Center. Her younger sister joined them at Chapei after her mother died from burns caused by an accidental fire. Sanborn left Shanghai in 1947 and moved to the United States. She attended boarding school in Greenville, Tennessee, then Earlham College, before attending Johns Hopkins University for a nursing degree.

Allie Marie Sanborn was born in Shanghai on July 25, 1930. Her father father James Gordon Sanborn moved to China to work as a milling engineer and met and married Allie's Chinese mother, Allie Marie Daugh. Her family initially lived in the French Concession before moving out to a newly built house on Hung Jao Road. She attended Asbury Academy and then the Public School for Girls. The family moved temporarily back into town after the Japanese occupation began, then back to the country, and then to an apartment at the mill where her father worked. They were later interned with her father and brother at Chapei Civilian Assembly Center. Her younger sister joined them at Chapei after her mother died from burns caused by an accidental fire. Sanborn left Shanghai in 1947 and moved to the United States. She attended boarding school in Greenville, Tennessee, then Earlham College, before attending Johns Hopkins University for a nursing degree.

On celebrating holidays:

"We celebrated all of the, all of the festivals and the religious holidays. Christmas was especially nice, there was just my brother and I and of course we were badly spoiled. We used to have a tree with candles on it that would get, that had, I said had candles on it and they would light it Christmas Eve, and we had to be very careful though, that things didn’t get on fire. And we had a dining room table that was round until you put the leaves in, and it would be piled high—they’d separate it, half with presents for him and half with presents for me. I remember one year, my mother said now, you, you always get so many presents and the children at the orphanage never get anything, so why don’t you gather some of your, some of your toys, the ones that you don’t want anymore, and I don’t want you to put in any broken ones, but let’s take them, you know, to the orphanage. So, I was a little annoyed by that. (laughs) Sometimes I could be difficult. And I had gotten this little toy piano that I used to pound on, so I thought humph, alright then, it was new, I said give them that piano. She said no, you just got that. She knew I was being mean...

...So we got it organized, and every year we, then we’d start taking things to the orphanage before Christmas so that they would have something. At New Years we always had firecrackers, it was wonderful...

I would always pick the kind of, I always got to pick everything and so I would pick the kind of firecrackers that I liked, that we wanted to see, that I would like to see—catchy wheels, and the big ones that exploded into pictures, and so forth. And then we’d have a little nap before midnight, and they’d wake me up, wake us up and we’d go out and watch the fireworks being put out on, put out, whatever. And then on New Years Day, there was the Chinese custom of exchanging money, in the little, in the little red envelopes, brand new. And so we would go visit all of our friends, our Chinese friends, and that would really consist of the owner of the mill. We would go to their house and exchange gifts, give them the red bags for their children and they would in turn had the bags for us, the envelopes. And then people would come over, on New Years Day, you know just to say hello and there’d be the usual goodies for them. And the children would be paraded out to say hello, speak your little piece, and you’d stand there thinking I don’t have anything to say. (laughs) At Easter time we had Easter egg hunts. Children would be invited over. So forth. What else? On the fourth of July we had fireworks, and we would go downtown and watch the parade. The Fourth Marines were stationed there and I used to love to watch them.

I went to the Asbury Academy...I remember we used to have Halloween parties there, dunking for apples and so forth, all the usual American things.

We would hear from my dad’s sister, he was, my dad came from a large family and he heard from the one sister regularly. And we used to write them regularly, and I was always the one who was elected to do the writing. And at Christmas time we would send them presents, and they would send us presents, and I can remember our going to the big post office downtown to collect them—they always sent fruitcake."

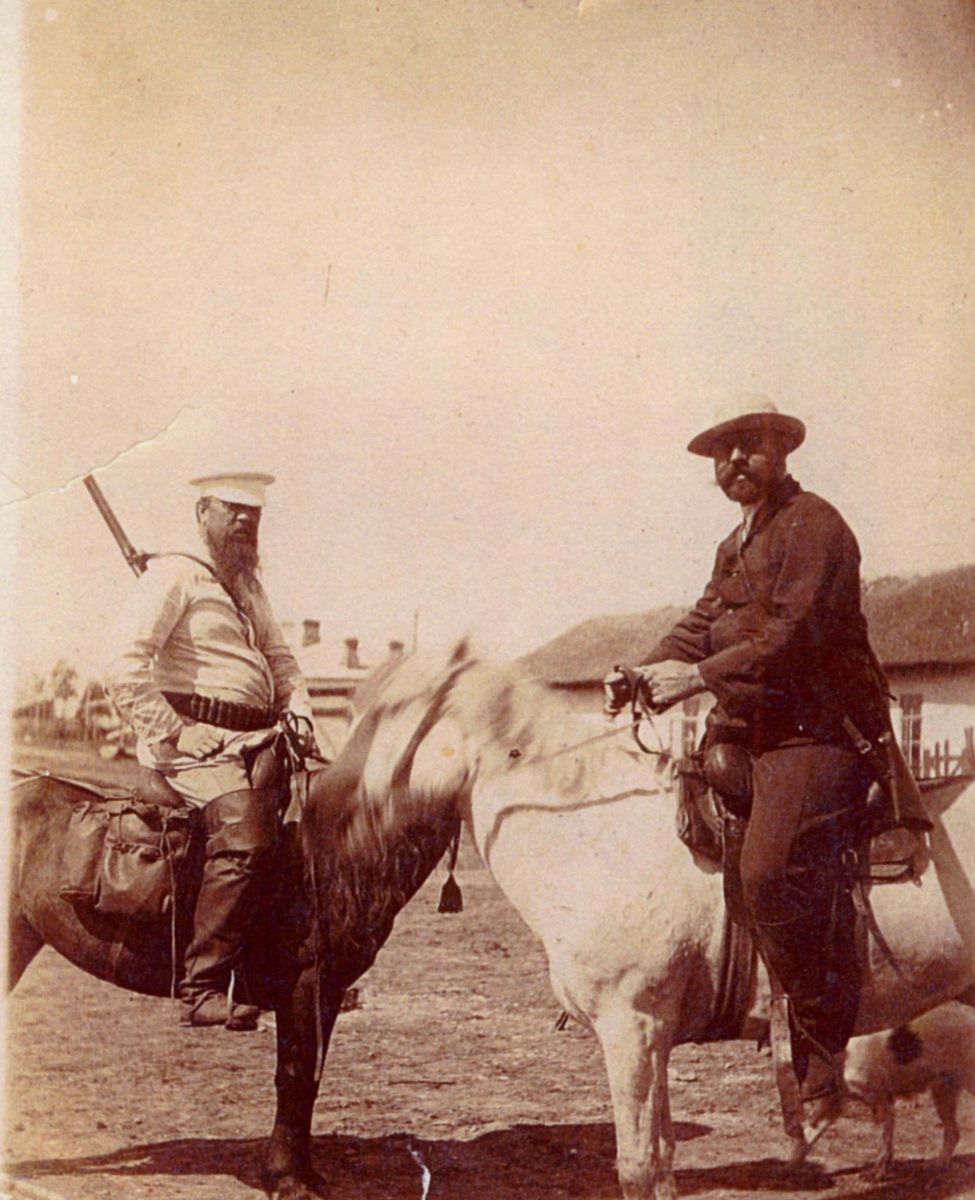

The Roman Edwards Collection contains photographs, ephemera, and a manuscript documenting Edwards' and his parents' lives in Shanghai and their internment in Yu Yuen Road Camp and Ningkou Road Civilian Assembly Center during World War II.

The Roman Edwards Collection contains photographs, ephemera, and a manuscript documenting Edwards' and his parents' lives in Shanghai and their internment in Yu Yuen Road Camp and Ningkou Road Civilian Assembly Center during World War II.

Roman "Ted" Edwards was born December 6, 1929 to a Russian mother and British father. His surname was originally Pisani. He attended St. Jeanne D'Arc school in Shanghai before attending Cathedral School. When World War II began he and his family were interned at Yu Yuen Road Camp. His family moved to England in May 1946 before immigrating to the United States in 1948.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: old china hands archives, photographs, archives

Read more Old China Hands Newsletter blog entries