Old China Hands Archives Newsletter, Volume 2, Number 2

March 09, 2022

From the Director: Ukraine and the Old China Hands

I write this as we witness the anguish resulting from the aggressive war waged by Vladimir Putin against Ukraine. Many Old China Hands may have their memories stirred by some of the words and place names occurring in the news: Ukraine, Moldova, Odessa, Crimea, Poland, refugee, separation, hunger, bloodshed, mass graves. As a child of refugees from the Russian Empire, born in Shanghai, I am moved by memories of my own family's history.

My Jewish fraternal grandfather and grandmother lived and died in Kishinev, Moldova, and their children chose Harbin and later, Shanghai and Australia, as refuges from pogroms, revolution, and wars. My maternal grandmother, the daughter of a prosperous businessman in St. Petersburg, also fled eastward to Manchuria and China, part of the tide of many Russian-speakers escaping the Russian Revolution and subsequent civil war. China also drew workers on the Chinese Eastern Railway branch of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Later, Shanghai provided a safe harbor for some of the Jewish victims of the Nazis in Germany, Austria, Poland, and the Baltic states.

It is quite likely that the Old China Hands Archives would not exist without the historic links between China and such places as Russia, Ukraine, Moldova and eastern and central Europe generally.

Today we witness the tide of millions of Ukrainians leaving their country to escape wilful and callous attacks on civilians. Many thousands of Russians are leaving their homeland as well, whether through fear of persecution by Putin’s dictatorial regime for their opposition to the war, to live in a free society, or from simple shame.

Refugees and their descendants made up a large proportion of the foreign population of China in the first half of the previous century and our hearts ache in sympathy for the victims of this war waged upon the citizens of a working democracy, a war inflicted by a Russia many of us have esteemed for its culture, art, science, language and literature, while we condemn its succession of autocratic and murderous rulers and the pain and suffering they have inflicted on their own people.

We, Old China Hands, harbor memories of dislocation and loss in our own pasts and extend our sympathy and support to Ukraine and its people.

Robert Gohstand, Ph.D.

Founder and Director

March 2022

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities.

The Old China Hands Archives contains collections that tell many stories about the push and pull factors that brought foreigners to China. Many came to China seeking a place of refuge, while others were pulled by business, religious callings, military service, government work, or other opportunities.

Missionaries were some of the earliest foreigners to reside in China. Jesuits arrived in China in the 16th century. Russian Orthodoxy and Protestant missionary activity grew rapidly after foreign nations signed treaties with China at the end of the Second Opium War in 1860. Missionary activity in China declined soon after the Communist takeover and suppression of religion in 1949. Over the following years missionaries departed voluntarily or were expelled.

Several collections document the histories of specific missionary families in China:

Robert and Eva Tharp Collection Robert Tharp was born in 1913 to British missionary parents in the Jehol Province of Manchuria. Evangeline (Eva) Kok was born in 1914 in Yunnan, China, to Dutch missionary parents. In 1918, the family moved to Peking (Beijing), where her father served as the First Chancellor of the Netherlands Legation in China. Eva attended the Peking American School, graduating in 1931. She then attended the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, and returned to China to perform mission work after graduating in 1936. Robert began working as a full-time missionary in beginning in 1934. During World War II they worked in India before returning to missionary work in China after the war, and ultimately leaving China in 1949.

Robert and Eva Tharp Collection Robert Tharp was born in 1913 to British missionary parents in the Jehol Province of Manchuria. Evangeline (Eva) Kok was born in 1914 in Yunnan, China, to Dutch missionary parents. In 1918, the family moved to Peking (Beijing), where her father served as the First Chancellor of the Netherlands Legation in China. Eva attended the Peking American School, graduating in 1931. She then attended the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, and returned to China to perform mission work after graduating in 1936. Robert began working as a full-time missionary in beginning in 1934. During World War II they worked in India before returning to missionary work in China after the war, and ultimately leaving China in 1949.

- Norman Filman Collection Norman J. Filman was born on November 23, 1920, in Calgary, Canada, and was taken to China soon after to live with his grandparents, John L. and Margaret Duff who had served as missionaries in the country since the early 1890s. He grew up in Kuling, China before attending the Western District Public School in Shanghai.

- Old China Hands Unpublished Manuscripts Collection This Collection includes Samuel J. Mills' "Boyhood in China" manuscript, which documents the history of his 19th century Presbyterian missionary family.

Additional collections in the Old China Hands Archives include a smaller number of photographs and research materials related to the presence of missionaries in China in the 19th and early 20th century.

The Ming dynasty first leased Portuguese Macau to Portugal as a trading post in 1557. The territory remained under Chinese sovereignty and Portugal paid for the privilege until the Sino-Portuguese Treaty of Peking in 1887, signed in the aftermath of the Second Opium War. In this treaty the Qing dynasty signed over to Portugal the perpetual colonial rights to Macau. Portuguese administration over Macau was reaffirmed with the 1928 Sino-Portuguese Treaty of Friendship and Trade.

In Portugal, a 1974 military coup overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime and prompted the beginning of decolonization. Shortly after this "Carnation Revolution," Portguese administrative and military personnel withdrew from Portugal's African colonies, but Macau continued for more than two decades as a Chinese territory under Portuguese administration. The Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration in 1987 set a timeline for the transfer of Macau sovereignty back to China on December 20, 1999. Once returned to Chinese rule, Macau became a Special Administrative Region, much like Hong Kong.

Several collections in the Old China Hands Archives document the Macanese community. Jorge P. Forjaz is an historian and published author whose works focus primarily on the genealogies of Macanese families, most notably Familias Macaenses, published initially in 1996. The Jorge P. Forjaz Collection consists largely of research materials compiled by Forjaz and used in Familias Macaenses. Records include correspondence between Forjaz and numerous contributors who provided family histories, legal documents, photographs, and memorabilia; the author's typescript, and manuscript, both with handwritten notes; extensive research records, notes and photographs compiled by the author.

Several collections in the Old China Hands Archives document the Macanese community. Jorge P. Forjaz is an historian and published author whose works focus primarily on the genealogies of Macanese families, most notably Familias Macaenses, published initially in 1996. The Jorge P. Forjaz Collection consists largely of research materials compiled by Forjaz and used in Familias Macaenses. Records include correspondence between Forjaz and numerous contributors who provided family histories, legal documents, photographs, and memorabilia; the author's typescript, and manuscript, both with handwritten notes; extensive research records, notes and photographs compiled by the author.

Series V, Fremont, California in the Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection, contains oral history interviews conducted by the Old China Hands Archives primarily at the Macau Cultural Center in Fremont, California. The bulk of these interviews are with descendents of Portuguese emigrants. The Lusitano Club of California runs the Macau Cultural Center. The Lusitano Club preserves and promotes the history, culture and heritage of the descendants of Portuguese people of the Far East, known as the “Macaenses.”

The Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection contains nearly 200 oral histories documenting a range of experiences. Interview topics include, but are not limited to, daily life in China, impressions of local culture and business, and experiences related to World War II such as the Japanese occupation and internment of Allied country citizens residing in China. Transcripts are available for most audio interviews. This issue we are featuring an excerpt of an interview conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1996 with Betty Code-Huseman.

The Old China Hands Oral History Project Collection contains nearly 200 oral histories documenting a range of experiences. Interview topics include, but are not limited to, daily life in China, impressions of local culture and business, and experiences related to World War II such as the Japanese occupation and internment of Allied country citizens residing in China. Transcripts are available for most audio interviews. This issue we are featuring an excerpt of an interview conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas, Nevada in 1996 with Betty Code-Huseman.

Betty Code-Huseman was born in Shanghai, China in 1929 to an American father and Japanese mother. She started kindergarten in Kobe, Japan, then attended Thomas Hanbury Public School for Girls in Shanghai until she was sixteen. Her father worked as an importer/exporter after leaving the U.S. Navy and was in India for most of World War II. She evacuated to the United States in 1945, but her father, mother, and younger brother remained in Shanghai until 1949. Her father returned to the United States for lung surgery, but died shortly after. Her brother came to the United States for school and her mother returned to Japan. In this excerpt Code-Huseman talks about her sense of identity as a child growing up in Shanghai:

Interviewer (I): Describe some of your experiences at that school [in Shanghai].

Betty Code-Huseman (BC): Most of our teachers were English, and they were fabulous educators. And I think my memories of school there are the unique position of, actually even if you wanted your pencils sharpened, we had a boy come in to collect our pencils and sharpen them for us. It was their job to see that the students had well-sharpened pencils. When I look back on that, it tells you the luxury of life that the foreigners led there, in having servants to do the most menial tasks that we really took for granted.

I: Were most of your classmates European, or Western?

BC: Most of them were European—many were part Asian, as I was. I think the wonderful thing about it was that all of my friends spoke different languages at home. I think one of the reasons why I wanted to come into this interview was because in the United States we are so hung up with bilingual education, which I find such a total waste of money. Because my experience was that all of us children went to this English school, this English-speaking school and we were all brought up in the King’s English, with most of us speaking different languages at home. Many parents who didn’t speak English at all—and yet the students came out with fine educations.

I: And, so your point would be that, that teaching English should not affect other people’s languages?

BC: Well, another thing is, you know in the United States, we still make a big thing about what kind of an American are you. I remember coming—being evacuated on a ship coming home, people would say, "What are you?" and I’d say American. And they said, "Well we know you’re American, what kind of an American are you?" Do you know I really didn’t know. My father had never told me what his background was, you know.

In Shanghai, if you were an American, that was enough. I never knew I was different, until I came back to the United States. I felt so multicultural, and looking back on, oh for instance the problems of Blacks and the Hispanics in the United States, you know they talk about not having any cultural background to identify with because they have transplanted as immigrants to the United States. But you know, there’s that unique lot of us that have no...country of cultural origin. I certainly don’t feel Japanese...Nor could I go to Japan and feel comfortable as a Japanese. And yet, in the United States I do speak English, but I don’t look like the rest of them. (laughs) So consequently, I’m not really what I feel is American.

I: And plus you spent your formative years in China.

BC: Exactly. So when you say what are you? What do you say other than, "I’m of Shanghai." You know, it’s really a unique—

I: Is that how you feel? You feel like, kind of like you’re from Shanghai?

BC: Yes. Yes.

I: What was it like for you being a kid in Shanghai.

BC: That’s my nationality...Even though we were all different.

I: Yeah. So what was it like being an American, of kind of mixed blood, in Shanghai? I mean, what was it like growing up in Shanghai as a kid?

BC: I didn’t know I was different.

I: Right.

BC: I don’t think anybody else did either because they were all different.

I: Right.

BC: You know, we celebrated Russian New Year, we celebrated Russian Easter, we celebrated our own Easters, and our own Christmases. We celebrated Chinese New Year, we celebrated with our Jewish friends for every Jewish holiday. It was a great adventure, being able to celebrate everything and anything together. Nobody cared what you were.

The complete transcript, along with transcripts for many other interviews conducted at the Old China Hands Reunion in Las Vegas in 1996, are available on Digital Collections or by request. For assistance with this collection, or access to other transcripts not yet available online, please contact the Old China Hands Archivist at mallory.furnier@csun.edu.

The Jensen Family Collection documents the lives of American Manley Charles Jensen, his Norwegian wife Sara Ludavica Haug, and the early years of their children Johan Waldemar Haug Jensen and Manley Charles Jensen, Junior. Manley C. Jensen, Senior was born in San Francisco, but his career took him initially to the Philippines and then to Dairen and Shanghai, China. He worked for Standard Oil for a number of years, before returning to the United States in the early 1940s. While living abroad he met Sara, and the two married in the Philippines. Photographs document Jensen’s career, family trips around China, Europe, India, and the United States, and masonic activities. Photographs and a number of scrapbooks created by Sara Haug Jensen document the social scene in 1930s Shanghai.

The Jensen Family Collection documents the lives of American Manley Charles Jensen, his Norwegian wife Sara Ludavica Haug, and the early years of their children Johan Waldemar Haug Jensen and Manley Charles Jensen, Junior. Manley C. Jensen, Senior was born in San Francisco, but his career took him initially to the Philippines and then to Dairen and Shanghai, China. He worked for Standard Oil for a number of years, before returning to the United States in the early 1940s. While living abroad he met Sara, and the two married in the Philippines. Photographs document Jensen’s career, family trips around China, Europe, India, and the United States, and masonic activities. Photographs and a number of scrapbooks created by Sara Haug Jensen document the social scene in 1930s Shanghai.

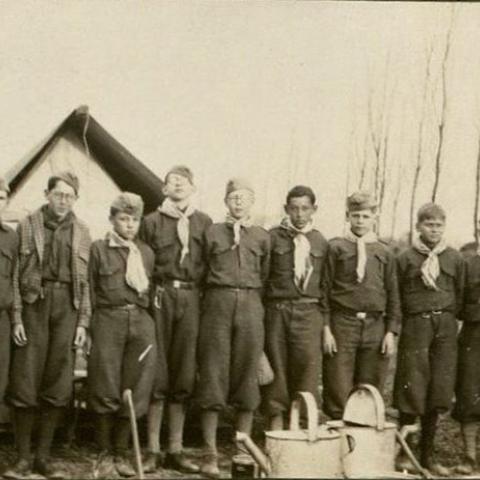

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: old china hands archives, photographs, archives

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries