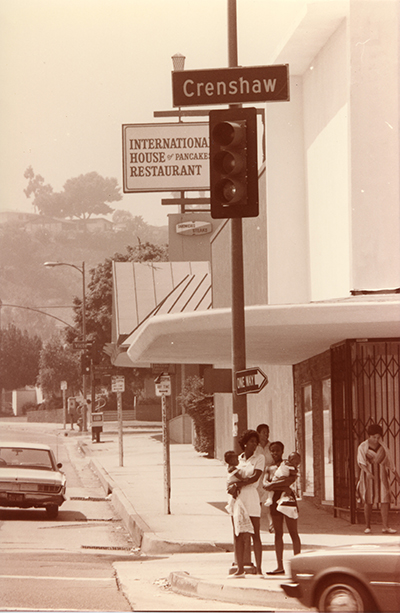

Crenshaw Boulevard: the Heart of Black LA

by Alohie Tadesse, Digital Collections Specialist, CSUN Special Collections and Archives/Digital Services - June 18, 2024

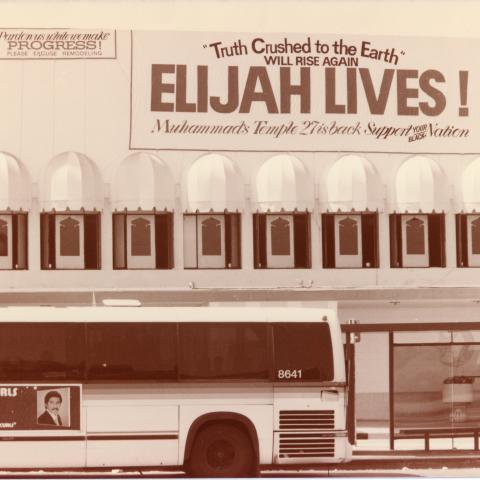

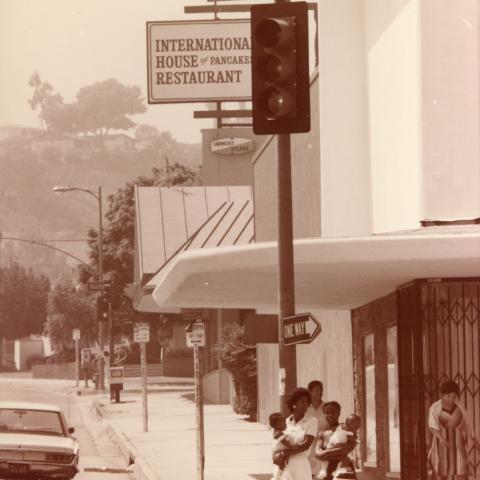

Crenshaw Boulevard is recognized as the commercial and cultural spine of Black Los Angeles. In recent years, however, surrounding neighborhoods in central Crenshaw have undergone dramatic change as “revitalization” projects promising opportunities for economic growth have threatened the historical and cultural character of this community. The Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at CSUN holds extensive photographic documentation of the communities in the Crenshaw District at their cultural height in the 1980s and 1990s. These images were captured by a number of black commercial and documentary photographers including Roland Charles, Guy Crowder, Harry Adams, Calvin Hicks, and Jack Davis. Roland Charles, originally from Louisiana, would go on to found The Black Gallery, one of the first art galleries dedicated to photography of black life, adjacent to the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Center in the heart of the community.

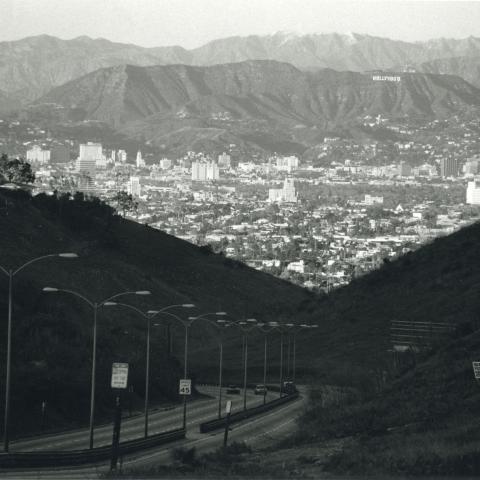

Crenshaw Boulevard is a 23-mile-long road that starts at Wilshire’s Mid-City District and ends at the scenic cliffs of Palos Verdes. The street was named in 1904 after the banker and real estate developer George Lafayette Crenshaw, and because of its natural beauty and central location it attracted middle- and upper-class white populations in its early years. Prior to World War II, many of the communities along Crenshaw barred non-white populations from owning property. After the 1948 Supreme Court ruling that disempowered the enforcement of racially restrictive housing covenants, Black and Japanese-American families flocked to Crenshaw’s surrounding neighborhoods such as Leimert Park and Baldwin Hills to become homeowners themselves.

Crenshaw Boulevard is a 23-mile-long road that starts at Wilshire’s Mid-City District and ends at the scenic cliffs of Palos Verdes. The street was named in 1904 after the banker and real estate developer George Lafayette Crenshaw, and because of its natural beauty and central location it attracted middle- and upper-class white populations in its early years. Prior to World War II, many of the communities along Crenshaw barred non-white populations from owning property. After the 1948 Supreme Court ruling that disempowered the enforcement of racially restrictive housing covenants, Black and Japanese-American families flocked to Crenshaw’s surrounding neighborhoods such as Leimert Park and Baldwin Hills to become homeowners themselves.

By the 1960s, these neighborhoods became predominantly African American as growing tensions between minority and white residents, the “close enough” 1965 Watts uprising, and racist fearmongering among realtors encouraging white residents to sell their homes, all culminated in dramatic white flight from Crenshaw’s central communities. According to a survey conducted by the Los Angeles Times in 1979, Crenshaw had, by the end of the sixties, gone from 65% white to 79% Black, 10% white and Latino, and 11% Asian. At the same time, nightlife and black entrepreneurship on and around Crenshaw thrived as Black-owned clubs such as the Memory Lane Supper Club and Mavericks Flat in Leimert Park hosted musical acts like Nat King Cole, The Temptations, and Marvin Gaye. After shows, former residents recall going to Holiday Bowl, a Japanese-American owned café and bowling alley on Crenshaw that served a multiethnic clientele.

In 1984, to support the shifting population, the Los Angeles City Council approved a redevelopment plan for the Crenshaw Center, a shopping center originally constructed in 1947 that had been on a major decline throughout the 70s. The mall would be renamed The Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza and became a community hub for its residents and Black business, hosting the annual Pan-African Film Festival and a weekly Farmers Market, and serving as the site for the Museum of African American Art. The Roland Charles and Calvin Hicks collections include extensive photography of the mall before and after this renovation. These photographs depict a vibrant social life, community organizing, and a landscape that has steadily changed over the years .

.

In recent years the mall, having gone through another decline, has been sold to a private investor that plans to rework its original design. Many of the other buildings and businesses down Crenshaw Blvd featured in these collections have been demolished and replaced by condominiums. By 1999, even Charles’ Black Gallery had to close its doors and donated its collections to the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center. In spite of these changes, Roland Charles and his colleagues have encapsulated this place and time in their photography so that it may never be forgotten. These photographs and more can be viewed by visiting Special Collections & Archives or by browsing the Digital Collections.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: bradley center, photographs, los angeles

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries