Emily Dickinson's Herbarium

by Philip W. Walsh, Ph.D., Lecturer, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies and Liberal Studies - February 28, 2023

Readers familiar with the work of Emily Dickinson (United States, 1830-1886) know that flower imagery appears frequently in her poems. Her interest in plants went beyond merely using them as metaphors in her work, however; throughout her life, she was an avid gardener, and her interest in botany was keen enough that her father built her a greenhouse. In fact, during her lifetime, she was better known in her native town of Amherst, Massachusetts, for her floral arrangements and gardening skills than for her poetry, and many of her friends only discovered her literary talents when they unwrapped one of her poems from a posy she had sent them.

Readers familiar with the work of Emily Dickinson (United States, 1830-1886) know that flower imagery appears frequently in her poems. Her interest in plants went beyond merely using them as metaphors in her work, however; throughout her life, she was an avid gardener, and her interest in botany was keen enough that her father built her a greenhouse. In fact, during her lifetime, she was better known in her native town of Amherst, Massachusetts, for her floral arrangements and gardening skills than for her poetry, and many of her friends only discovered her literary talents when they unwrapped one of her poems from a posy she had sent them.

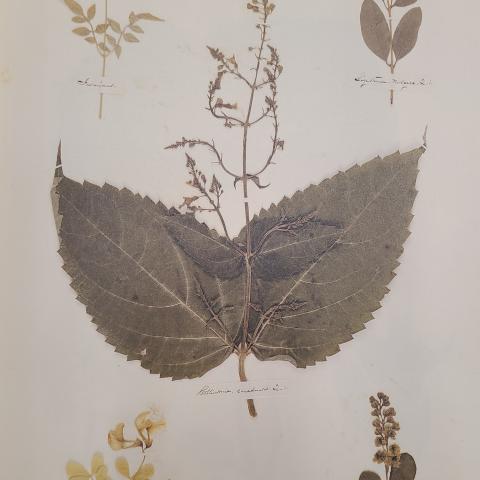

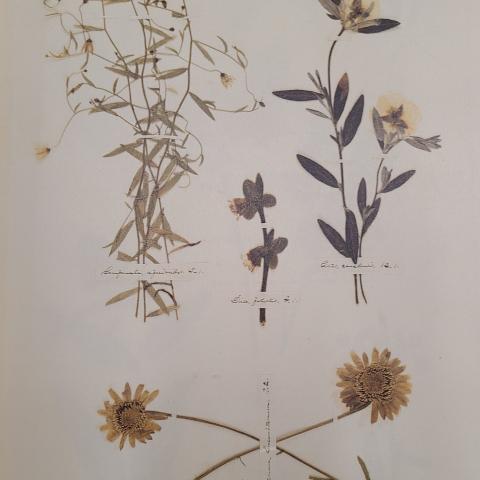

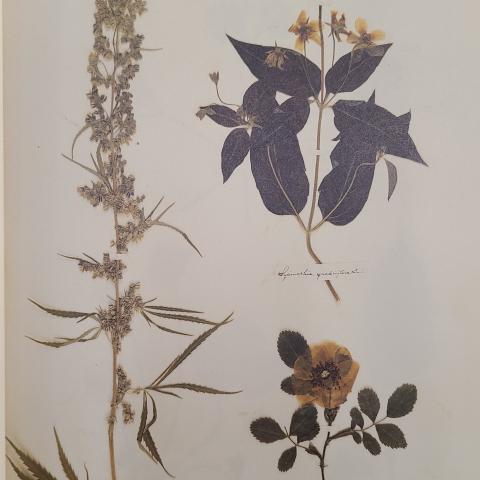

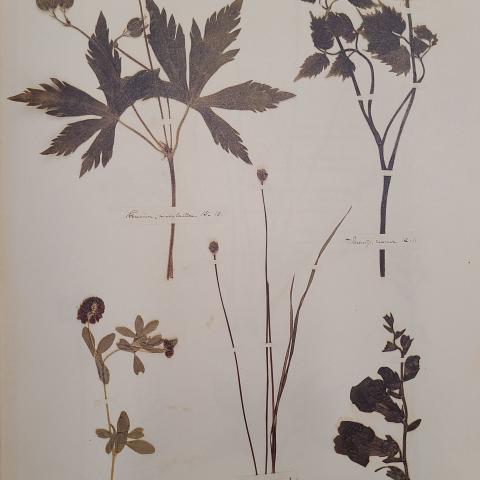

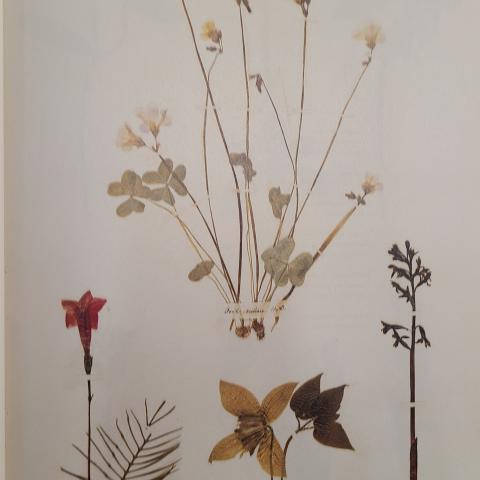

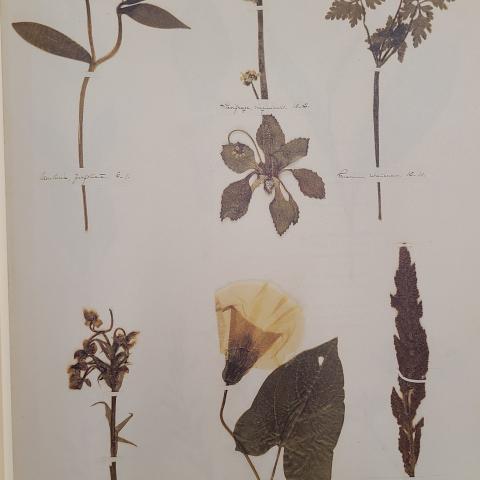

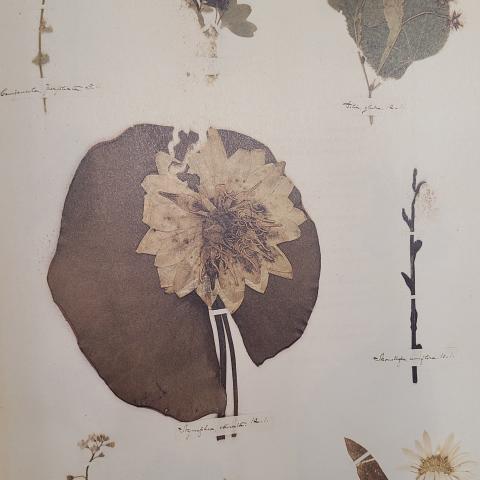

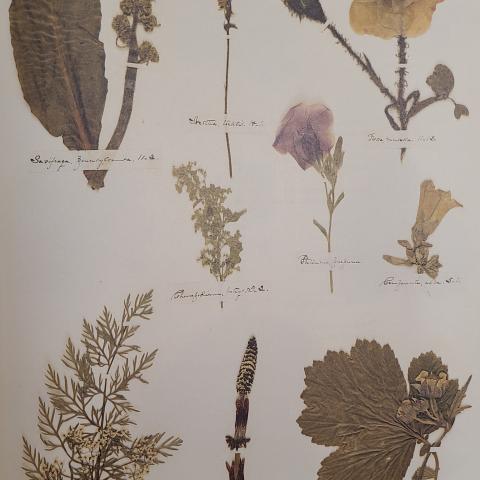

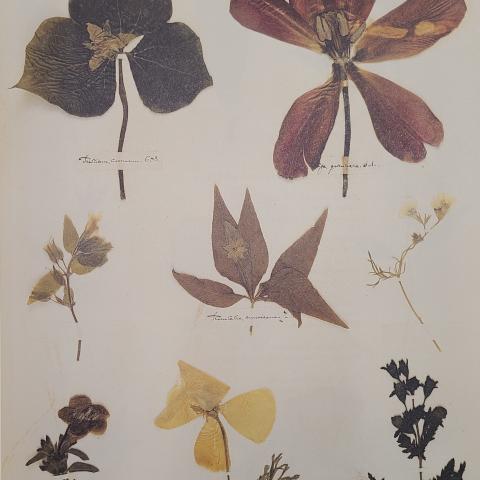

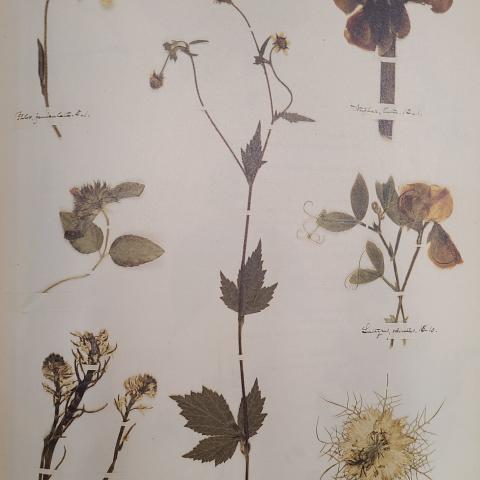

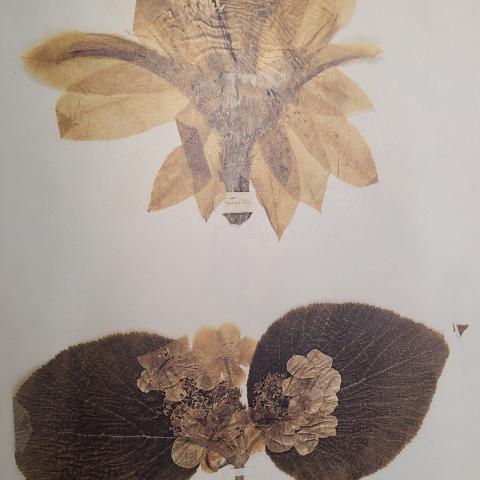

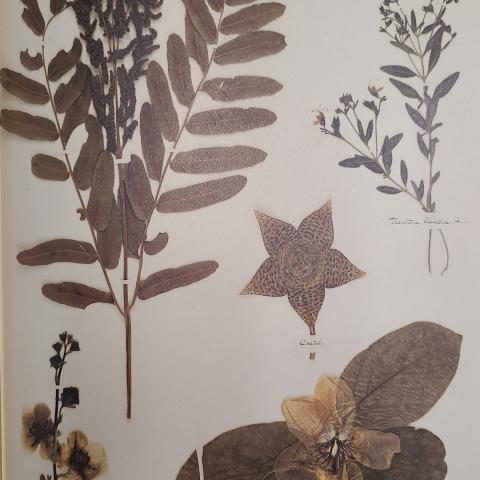

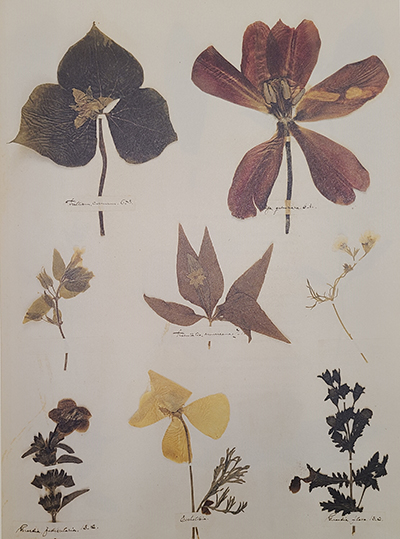

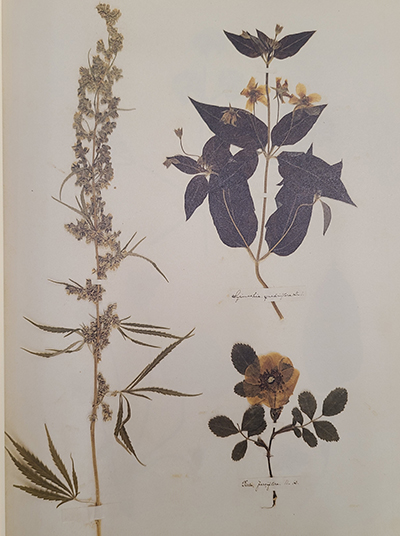

Her love of botany was reinforced by the classes in the subject she took at Amherst Academy, which she attended between the ages of ten and seventeen. Perhaps inspired by her studies there, she assembled an herbarium—a book, manufactured for this purpose, in which collectors can preserve plants—when she was a teenager. Dickinson pressed samples from her garden and nearby forests, marshes, and meadows into hers. Her hobby of collecting and preserving these plants had a powerful effect on her work; as one critic wrote, the flowers she pressed for her herbarium suggested many of the themes evident in her poetry.

There is, of course, only one original Dickinson Herbarium, which is held at Harvard University; Special Collections & Archives at CSUN has a facsimile. Making the original item available to researchers has been a challenge, since the specimens contained in the book are extremely fragile, and so, with few exceptions, the herbarium is preserved in a vault, with only limited access provided to researchers. It was displayed by Harvard Library in conjunction with its exhibit “Emily Dickinson: A Life in Writing, 1830-1999.” In preparation for this display, Harvard’s Curator of Manuscripts consulted with the Senior Collections Assistant at the university’s botanical museum. For decades, researchers could access only the black and white photographs of the book taken in the 1980s, until 2006, when Harvard published this facsimile, which features full color photographs. The facsimile contains essays by literary scholars, botanists, and archivists, and as such parallels the widely ranging multidisciplinary mind of Dickinson herself, who, hermit though she may have been in her later life, spent her youth wandering the gardens and uncultivated terrain surrounding Amherst.

There is, of course, only one original Dickinson Herbarium, which is held at Harvard University; Special Collections & Archives at CSUN has a facsimile. Making the original item available to researchers has been a challenge, since the specimens contained in the book are extremely fragile, and so, with few exceptions, the herbarium is preserved in a vault, with only limited access provided to researchers. It was displayed by Harvard Library in conjunction with its exhibit “Emily Dickinson: A Life in Writing, 1830-1999.” In preparation for this display, Harvard’s Curator of Manuscripts consulted with the Senior Collections Assistant at the university’s botanical museum. For decades, researchers could access only the black and white photographs of the book taken in the 1980s, until 2006, when Harvard published this facsimile, which features full color photographs. The facsimile contains essays by literary scholars, botanists, and archivists, and as such parallels the widely ranging multidisciplinary mind of Dickinson herself, who, hermit though she may have been in her later life, spent her youth wandering the gardens and uncultivated terrain surrounding Amherst.

The dandelions, asters, and irises she collected in her herbarium were identified only by their scientific rather than their common names. She sometimes continued this practice in her writing, referring in her poems to plants such as hawkbit, a type of dandelion, as Leontodon, the trailing arbutus as Epigea, and the leatherflower as Clematis.

There are also many unusual or otherwise memorable specimens in her collection, including poison ivy (which she mislabeled as Celastrus scandens, or climbing bittersweet), Cannabis sativa (which she did not label), the insectivorous pitcher plant Sarracenia purpurea, and the parasitic ghost plant or Indian pipe, which appears in two of Dickinson’s poems, and with which she identified strongly.

Despite her use of scientific names, Dickinson’s herbarium is clearly the creation of an amateur. The arrangement of the plants is more poetic than taxonomic; the first page features the fragile jasmine beside the hardier European barberry—these plants, one critic asserts, reflect two sides of Dickinson’s personality. The collection is skewed toward the more remarkable plants in Amherst and its environs, emphasizing flowers and odd plants over the more common grasses, mosses, and algae—all nearly absent—which a more comprehensive collection would have included. These gaps make the herbarium of limited use to a professional botanist, but to a student of Dickinson’s poetry, it reveals her lifelong love of plants and gardening, of Amherst’s gardens and the nearby wilderness, in which the young Dickinson played, worked, and wandered.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: special collections, rare books, united states

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries