Not so Distant: A Letter from 1919

April 28, 2020

While we are working, attending class, and doing so many other things from home, our blog posts will focus on materials that have been digitized and can be accessed remotely. We’ll continue to include links to our finding aids and other information about physical access, as well.

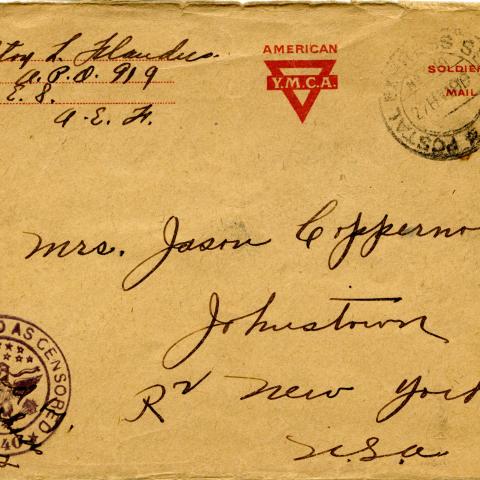

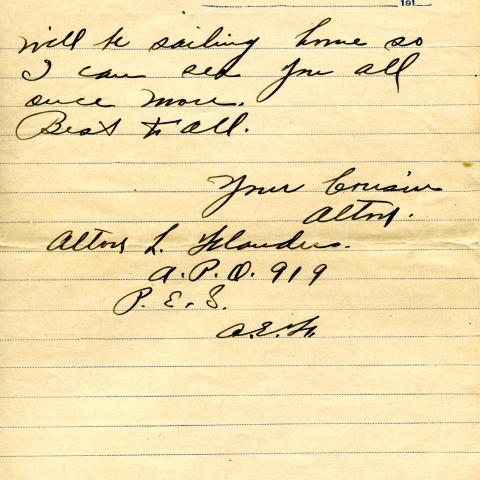

Alton L. Flanders served in an American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F) infantry battalion during World War I. He wrote letters to his cousin, Mrs. Jason Coppernoll, while in training at Camp Devens in Ayer, Massachusettes, and while stationed in France with the A.E.F. These letters make up the Alton F. Flanders World War I Correspondence Collection, and have been fully digitized as part of the World War I Narratives digital collection.

Alton L. Flanders served in an American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F) infantry battalion during World War I. He wrote letters to his cousin, Mrs. Jason Coppernoll, while in training at Camp Devens in Ayer, Massachusettes, and while stationed in France with the A.E.F. These letters make up the Alton F. Flanders World War I Correspondence Collection, and have been fully digitized as part of the World War I Narratives digital collection.

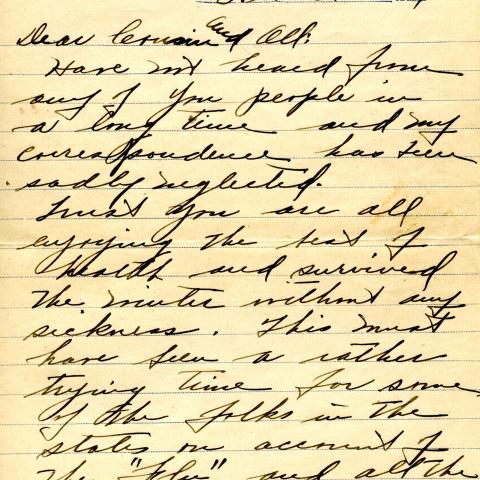

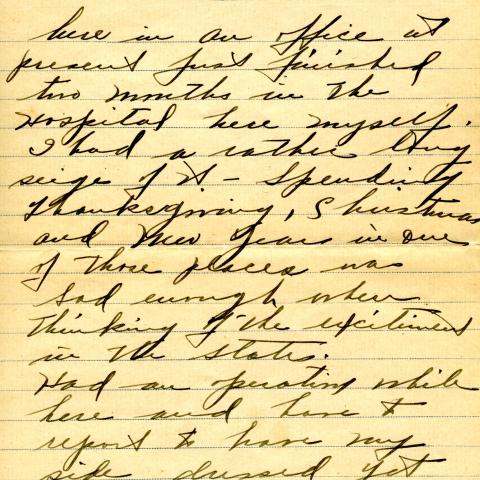

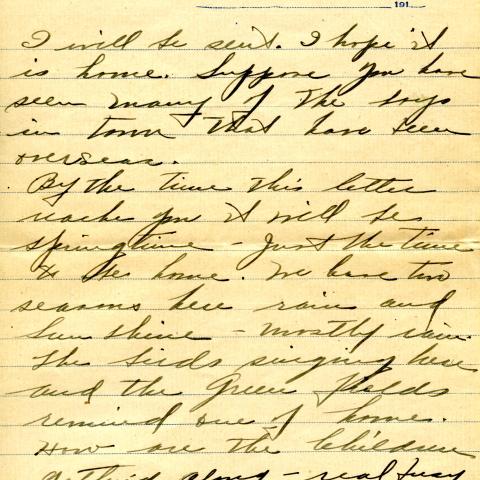

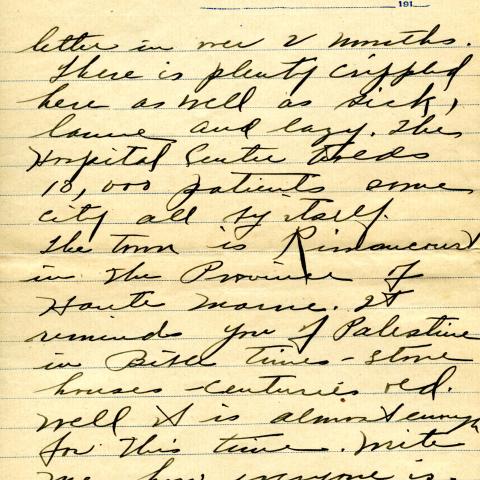

Flanders wrote the last letter in this small collection while in France in February 1919. In it, Alton writes that he hopes the family has passed the winter "without any sickness," and commiserates about what he describes as "a rather trying time for some of the folks in the states on account of the 'flu' and all the sickness we read about in the papers," referring to the influenza pandemic that ultimately killed tens of millions of people around the world. Later in the letter Flanders shares that he himself is feeling well, but that he "had a rather long siege of it," just having finished a two-month stay in the hospital. He lets his cousin know he had an operation while there, and still has his surgical wounds re-dressed daily at the hospital, where there are "plenty crippled ... as well as sick."

Flanders' language is a little vague and unclear. It's difficult to know if he had the flu himself while in the hospital, or not, which may have been intentional on his part. War-time censors in the US and other nations fighting World War I worked to conceal the true impact and severity of the pandemic as they feared weakened morale both on the front lines and at home. Indeed, in addition to the vague description of the cause for his hospital stay, the letter Flanders wrote in February 1919 also contains little geographic or other identifiable information that might be useful to the enemy if intercepted. The envelope is stamped as having passed A.E.F. censors on its way to Mrs. Coppernoll.

Flanders wrote this letter to stay in touch with friends and family, and maintain a sense of community while far from home. As people around the world experience life in the midst of a new pandemic in 2020, these same letters can be a valuable resource as we seek information about the experiences of people who lived through a similar event a century ago. Future historians will want to know how people alive in 2020 experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, especially how we reacted to the crisis, navigated having our basic needs met while social distancing, passed our days while sheltering in our homes, attended class, worked, struggled, and supported each other.

As our lives abruptly shift and change to meet the moment, we have probably all created written and electronic records that document our experiences as messages to family and friends, social media posts, drawings, photographs, poems, and more. These records might focus on feelings of worry and loneliness, or more practical struggles like getting groceries or figuring out how to use Zoom. Or, like Flanders' letters, they might refer to the pandemic more incidentally, mentioning things like sheltering at home and social distancing only in passing as these practices become increasingly normalized.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: special collections, archives, correspondence, united states, international

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries