Wartime Jewish Émigrés

November 10, 2015

Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi) gained control of the German state in 1933, after which the systematic and deliberate exclusion of Jews rapidly escalated. In 1933 Hitler called for a ban on Jewish business and the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service banned Jewish people (and some political opponents) from the civil service, including employment as teachers, professors and judges. Soon after this a similar law banned Jews from several other professions including doctor, musician, notary and lawyer. Initial exclusions for World War I veterans and their children were disallowed after Paul von Hindenburg’s (President of the Weimar Republic) death in 1934.

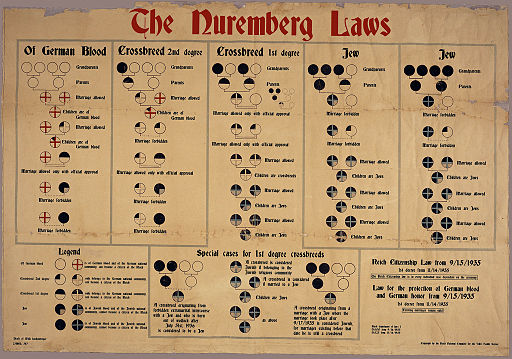

The Nuremberg Laws (1935) consisted of two separate laws whose purpose was to socially isolate Jews from Germans. The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour made both marriage and sexual relations between Germans and Jews illegal, and the Reich Citizenship Law made citizenship dependent on birth status, as in those of German (or related) blood. This law was later expanded to also exclude Romani and Black people as well.

The Nuremberg Laws (1935) consisted of two separate laws whose purpose was to socially isolate Jews from Germans. The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour made both marriage and sexual relations between Germans and Jews illegal, and the Reich Citizenship Law made citizenship dependent on birth status, as in those of German (or related) blood. This law was later expanded to also exclude Romani and Black people as well.

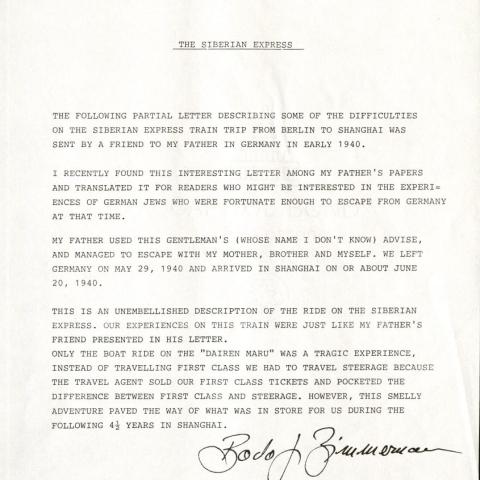

Germany also made it difficult for people to voluntarily emigrate since the vast majority of their belongings (i.e. wealth) would have to be relinquished to the state. This is made clear through personal reminiscence in the Bodo Zimmerman Collection, a small collection detailing the trip from Germany to Shanghai. The translation of a (partial) letter to Zimmerman’s father briefly describes the process of leaving Germany, including some of the difficulties. The letter notes government offices that had to be consulted and some of the financial ramifications of leaving Germany.

“I don’t have to mention to you that a trip out of Germany without a clearance from the finance department, the labor exchange and the foreign exchange department would be impossible. The shipping of household goods is practically impossible because of many restrictions...But since you are only allowed to take 10 marks per person out of Germany you have to make plans for the remaining 10 days [for food].”

The Stephan E. Stuart Collection documents the movements of one of the many Jewish émigrés that left Nazi Germany and its occupied territories in the 1930s and 40s. Special Collections and Archives houses a small collection of Mr. Stuart’s personal papers, allowing us to trace his emigration to the United States. For instance, based on school records dating from 1930-1931 we know that he lived in Germany. Based on the extension of his identification papers we known that he was in France no later than 1939. We can continue to trace his migration via this documentation, knowing that he was in contact with the Portuguese Commission for Assistance to Refugee Jews by December 1940 and that he was in the United States by 1941 when he registered for the U.S. Selective Service (draft).

Not knowing exactly when he left Germany makes the assertion that he fled Nazi persecution difficult however it is clear that the tide of public opinion in Germany was turning during the time for which we have no documents, 1931-1939. We also know that the German occupation of France began in July of 1940, therefore the assumption that he was, by 1940, attempting to flee Nazi rule begins to gain credence.

The Jewish Family Service of Los Angeles Oral History Project Collection contains several interviews with Jewish people that emigrated from Germany or German occupied territories from 1930 to 1950, the years marking the rise of Nazism through the immediate post-war. These interviews illuminate numerous paths; at least one went to Palestine before coming to Los Angeles; others went through Turkey, England or Spain; one came through Jamaica and another, Cuba. There are stories of the Warsaw Ghetto, Zionist activism, and the Gestapo.

Information regarding assistance to Jewish refugees can be found in the papers of the Jewish Federations Council of Greater Los Angeles, Community Relations Committee Collections, especially in Part II of that collection. There are files relating to several relief organizations, mostly notably the National Refugee Service (note that the official records of the National Refugee Service are located at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Center for Jewish History in New York).

According to the American Holocaust Memorial Museum nearly 300,000 Polish Jews fled to the east, making it to the Soviet Union prior to the Nazi offensive on the Eastern Front. They give numbers of 30,000 entering Switzerland and an additional 30,000 entering Spain, most of whom were reportedly passing through on their way to the Americas. They also state that “virtually the entire Danish Jewish community” escaped to Sweden. An additional 18,000 fled through the Balkans to Palestine, and approximately 43,000 were sheltered in Italian occupied zones in Yugoslavia, France, and Greece.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: urban archives, old china hands archives, correspondence

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries