What About the Werewolf?

October 29, 2019

This week’s blog post shines (moon)light on just a few of the books in Special Collections on the werewolf and lycanthropy, from reprints of classical Greek and Roman texts to mid-twentieth century discourse and compilations. What do you know about werewolves, the difference between werewolves and lycanthropes, and why do so many cultures have werewolf legends?

This week’s blog post shines (moon)light on just a few of the books in Special Collections on the werewolf and lycanthropy, from reprints of classical Greek and Roman texts to mid-twentieth century discourse and compilations. What do you know about werewolves, the difference between werewolves and lycanthropes, and why do so many cultures have werewolf legends?

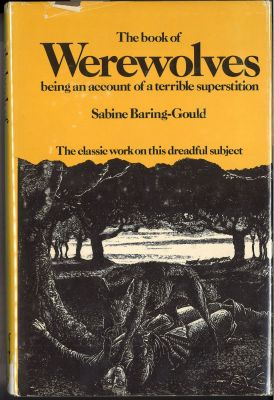

Widespread consensus indicates a werewolf is a man, woman, or child who changes shape into that of a wolf, either voluntarily or involuntarily. The change is most often temporary, but can sometimes be permanent. They appear to themselves and to others as wolves, in both shape and behavior. Folk tales, stories, and myths from around the world have different methods by which werewolves exist or are created: through heredity, via a curse, from magic, or by being bitten by another who suffers from the affliction. Unlike werewolves, lycanthropes lose their sanity entirely after transformation, suffering from "[m]ania or disease,” according to Montague Summers, and described as being possessed by "[a] form of madness" by Sabine Baring-Gould

In The Satyricon of Patronius, Niceros tells a tale of travelling the road with a brave friend who was a soldier. The soldier turned into a wolf before Niceros’ eyes, then ran off. Upon arrival at his destination, Niceros was told that a wolf had recently killed all the sheep, and been speared through the neck. At home the next day, Niceros found his friend in bed, with a doctor tending a neck wound.

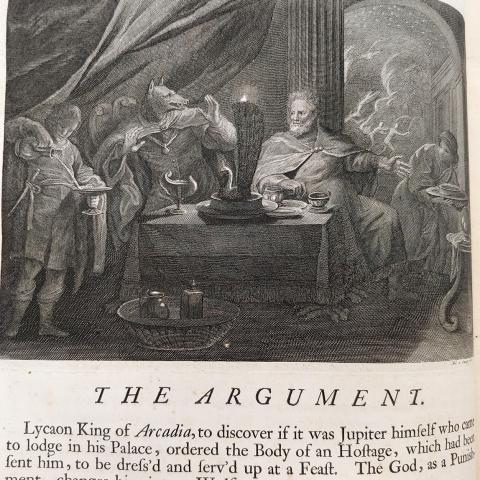

Some scholars believe the transformation from man into wolf in the Epic of Gilgamesh (ca. 2100 BCE) is the first mention of lycanthropy in the west. In this story, the goddess Ishtar transforms a lovelorn shepherd into a wolf. Similarly, Ovid’s Metamorphoses (ca. 8 CE) tells of King Lycaon of Arcadia's attempt to deceive Jupiter via transformation into a wolf, and his subsequent punishment. It is this story that gives us the word lycanthrope.

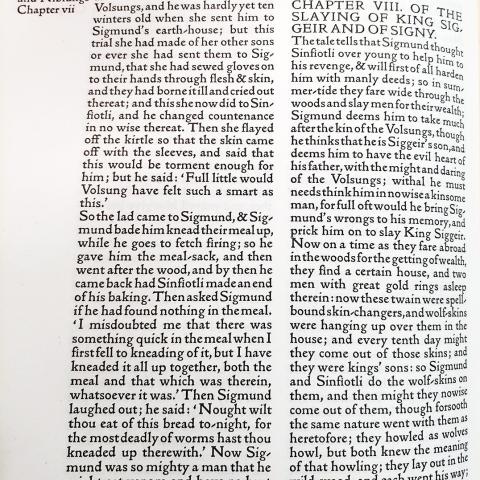

The Völsunga Saga, a medieval Norse saga, also has a story of lycanthropy. Heroes Sigmund and Sinfjötli find two men, apparently asleep, with wolf skins hanging above them. They steal the skins, put them on, and transform into wolves. They have "many famous deeds in the kingdom" until Sinfjötli fights a battle without Sigmund, who is angry at being left behind and bites Sinfjötli. Sinfjötli is saved by an unnamed herb, after which the two heros abandon the wolf skins. In this translation they burn the skins so that others will not come to harm.

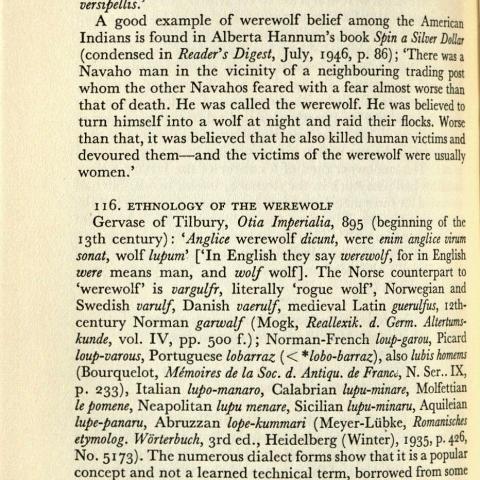

The Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould first published The Book of Werewolves, being an account of a terrible superstition in 1865. One chapter is titled "Folk-Lore Relating to Were-Wolves," and highlights stories featuring transformation, though not necessarily into wolves, from India, Armenia, North America, and other places around the world. One of these stories is from the Tlicho (or Dogrib), First Nations people living in what is now the Canadian Northwest Territories. In it, a young man lived alone with only his dog who had a litter of eight pups. When the man went fishing, he tied the puppies up so they wouldn’t stray. Coming home one day he thought he heard talking and laughter. Curious he feigned going fishing and hid nearby. When he heard the talking again he came upon eight small children, dog skins off to the side.

Robert Eisler, in Man Into Wolf, an anthropological interpretation of sadism, masochism, and lycanthropy, theorizes an evolutionary root to violence at least partially based on Jungian archetypes of collective unconscious. He claims the basis of werewolf legends throughout the world lie in the evolution of hunting while wearing animal skins, techniques developed during the last ice age.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: special collections, rare books, publications, international

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries