Shades of Inspiration: Barry Moser’s Literary Illustrations

by Philip W. Walsh, Ph.D., Lecturer, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies and Liberal Studies - October 21, 2025

Barry Moser is an artist, author, and illustrator, and the founder of Pennyroyal Press, an engraver and book publisher. He has illustrated over 150 books during his career, favoring black and gray paints and inks, in most cases.

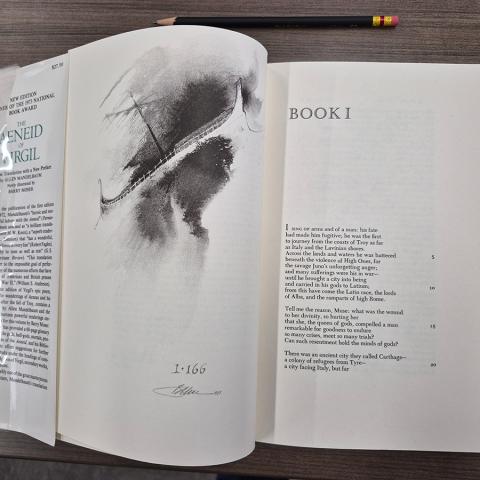

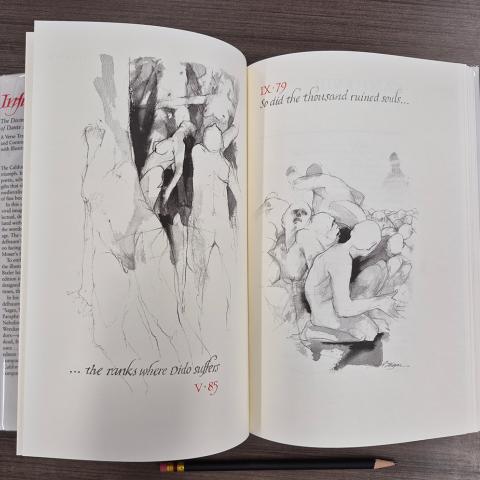

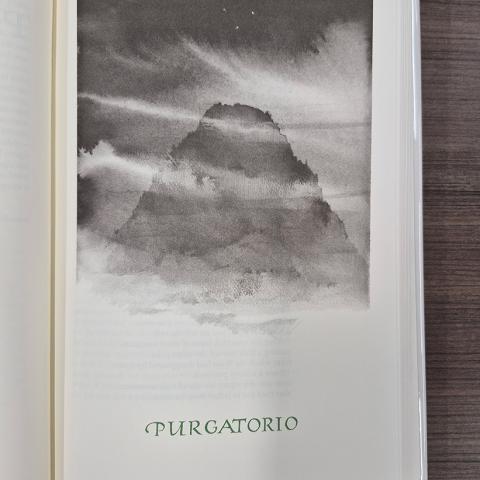

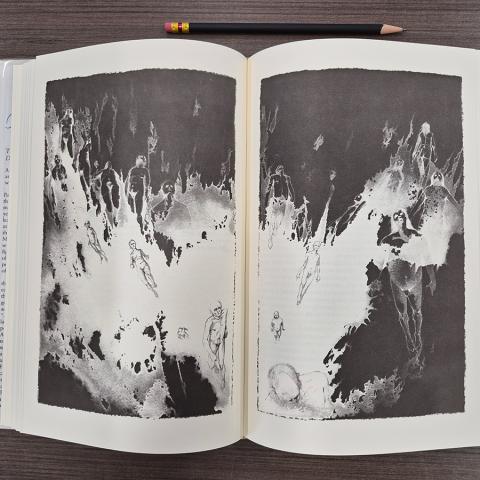

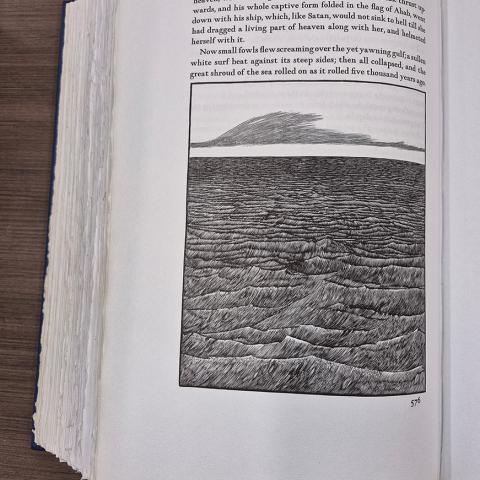

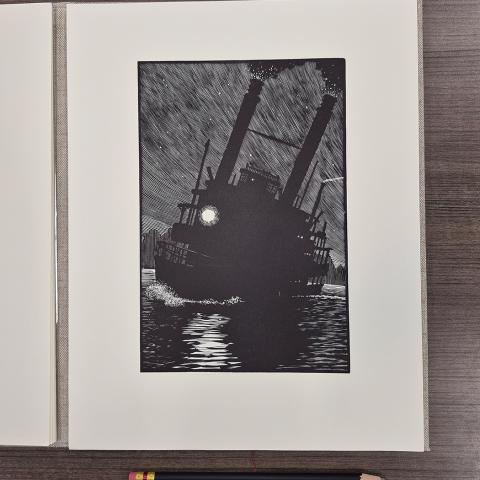

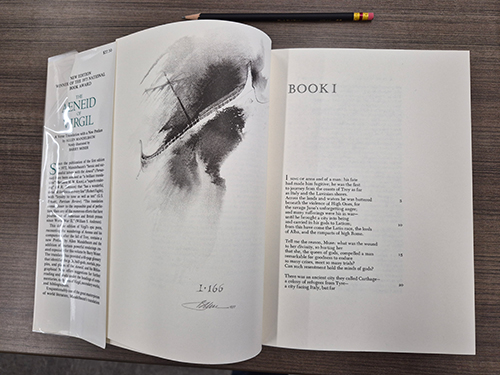

His first image for Allen Mandelbaum’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid,  for example, portrays the Trojan’s ship, battered by the sea, as a white slash in a black space. Moser continues to use this technique in Mandelbaum’s version of Dante’s Divine Comedy (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), whose images he "stated first with a pencil, loosely blocking the arrangement and placement of figures." He then overlaid them with "dark washes and thick, black ink." His illustrations move, he writes, "from a pale Hell to a dark Paradise—the opposite of what is expected." One of the reasons he made this choice is that Dante’s Paradise, he writes, "is full of brilliant lights that punctuate darkness...Graphically, light can be represented only by the whiteness of the paper, then only when it is surrounded by darks."

for example, portrays the Trojan’s ship, battered by the sea, as a white slash in a black space. Moser continues to use this technique in Mandelbaum’s version of Dante’s Divine Comedy (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), whose images he "stated first with a pencil, loosely blocking the arrangement and placement of figures." He then overlaid them with "dark washes and thick, black ink." His illustrations move, he writes, "from a pale Hell to a dark Paradise—the opposite of what is expected." One of the reasons he made this choice is that Dante’s Paradise, he writes, "is full of brilliant lights that punctuate darkness...Graphically, light can be represented only by the whiteness of the paper, then only when it is surrounded by darks."

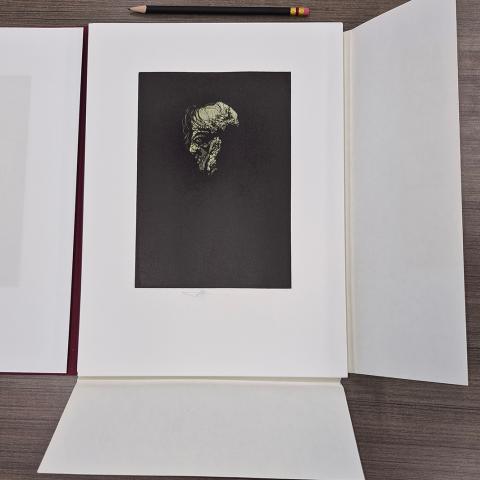

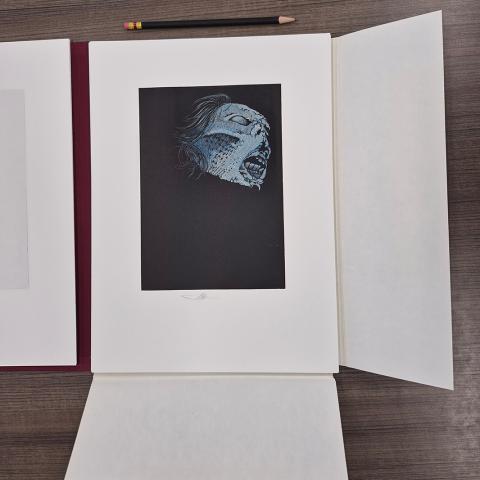

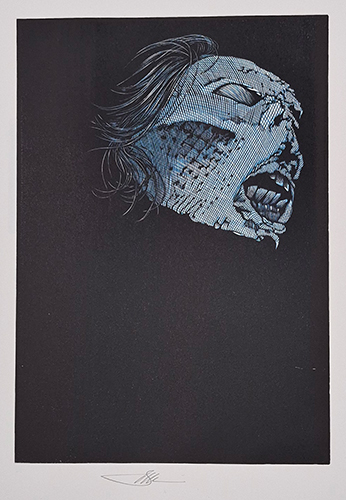

He makes similar choices in his interpretation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. All of the engravings are black and white, with the exception of Frankenstein’s creature, who is colored in pale shades of yellow and green, with hatching to make the entire image darker. Only at the moment that the creature announces his intention to destroy himself on a funeral pyre is his face illumined by a vibrant electric blue, identical to that of the image of lightning on the first pages of this edition. The creature resembles a mummified corpse; only in one image, the scene in which Frankenstein hallucinates the creature in his bedchamber, do his eyes, expressing deep sorrow, appear truly alive.

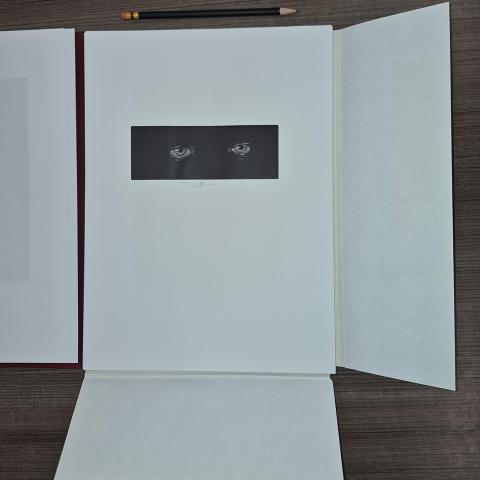

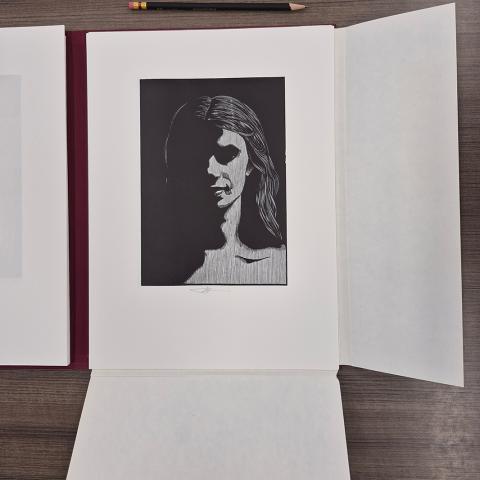

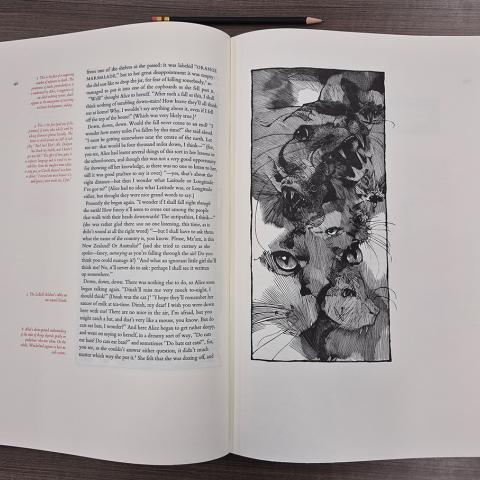

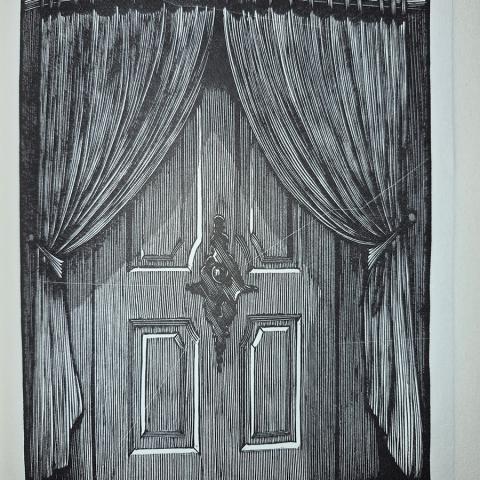

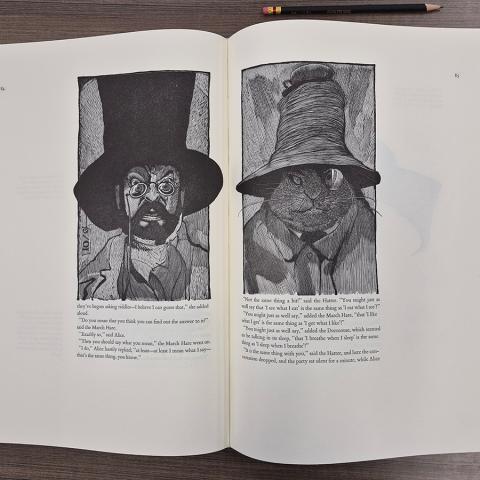

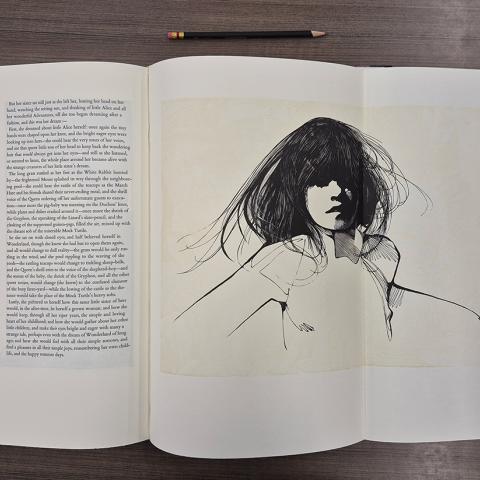

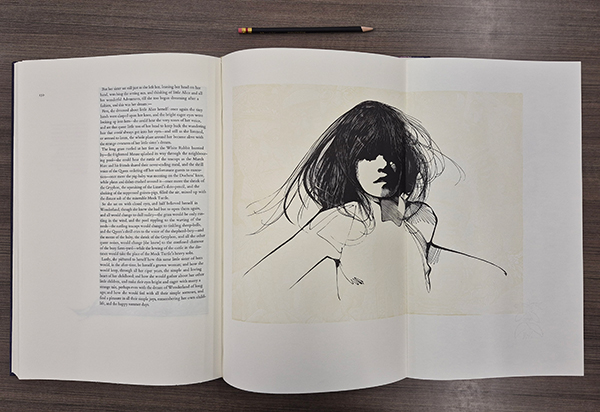

Moser’s illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are in most cases brighter than those of his Frankenstein, but in some cases almost as horrible. Alice, falling down the rabbit hole, plays a word game: "Do cats eat bats?...Do bats eat cats?" The illustration for this scene shows the faces of both animals merged together, their sharp teeth showing. And Alice herself, with her hair wild and her eyes in shadow, resembles a feral child more than she does than Tenniel’s neatly dressed young lady of the Victorian Era.  During this edition’s production, the printing blocks cracked under the eight thousand pound press, creating gaps in the finished artwork, which Moser allowed to remain; they are visible in the print of a doorway early in the narrative.

During this edition’s production, the printing blocks cracked under the eight thousand pound press, creating gaps in the finished artwork, which Moser allowed to remain; they are visible in the print of a doorway early in the narrative.

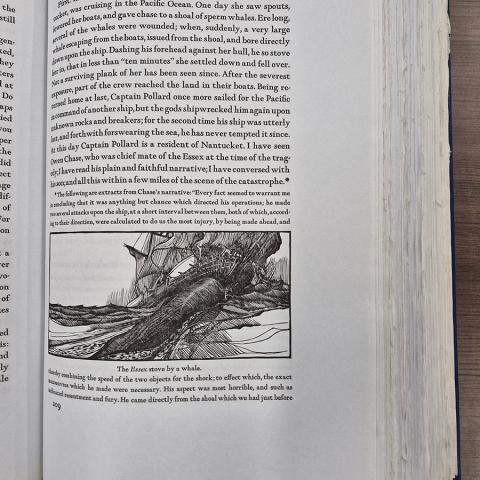

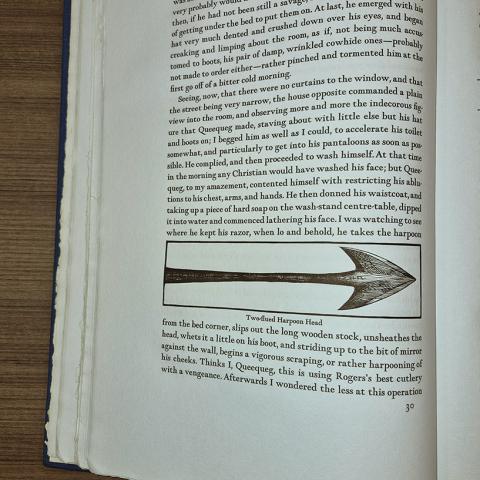

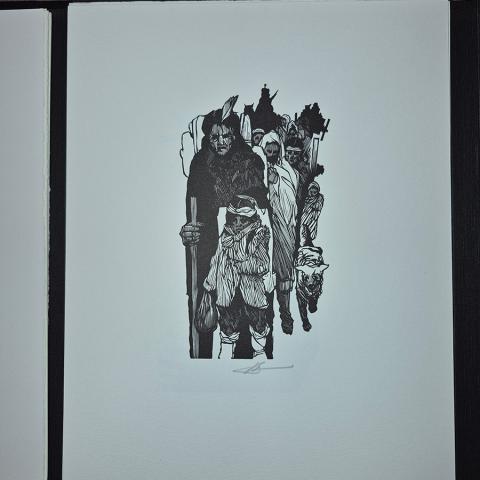

Moby Dick features several images of sea life, including a whale attacking the Essex, a whaleship whose story was an inspiration for Melville’s novel, but most of the images are of the tools of the whaler’s trade. So too does his portfolio of wood engravings Gold Rush feature miner’s tools. Other images show miners "crazed with lust for wealth;" the impact this greed has on others is evident in his engraving of the Trail of Tears, the forced displacement of about sixty thousand Native Americans from the southeastern United States after the discovery of gold in Georgia in 1828.

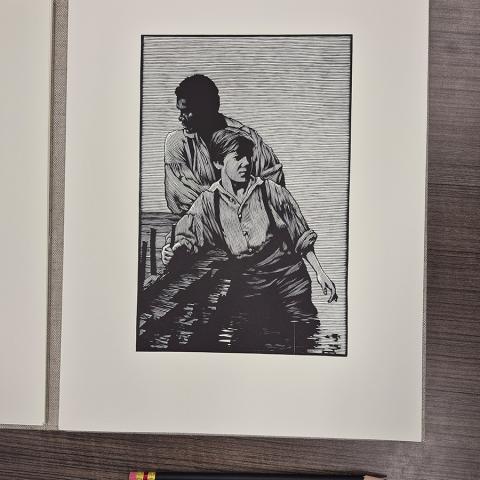

Moser uses hatching as a technique extensively throughout his work, but his Huckleberry Finn uses it more than most. Hatching has often been used to portray people of color, distinguishing them from whites who are not drawn or engraved with such shading; in Moser’s interpretation, every character in the novel is portrayed with hatching, thus reiterating Twain’s critique of the racial hierarchies of the antebellum South.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: special collections, rare books, united states

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries