Challenging the Racist Status Quo – Caroline Bond Day

by Gayle O’Hara, University Archivist, Special Collections & Archives - February 10, 2026

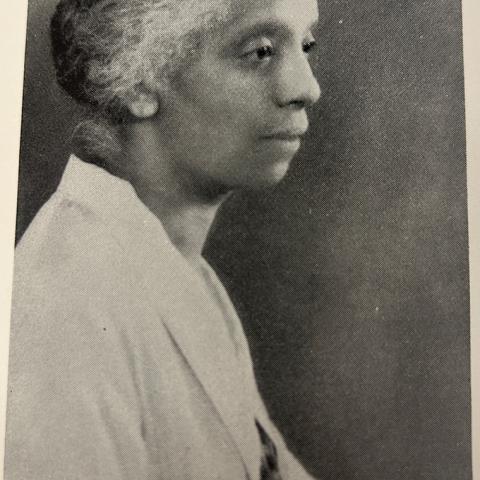

Scientific racism has been with us and used to justify racial hierarchies, discrimination, enslavement, and more for hundreds of years. While scientific racism was mostly discredited in the mid-20th century, given the current state of the world it is important to be vigilant and not let it gain a foothold again. One of the individuals in the earlier part of the 20th century who helped to challenge scientific racism and eugenics is Caroline Bond Day (1889-1948). Ms. Day earned her master's in anthropology in 1930, making her one of the first Black people to earn a graduate degree from Radcliffe College in Boston. CSUN’s Special Collections & Archives holds her master’s thesis, A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, which is still considered ground-breaking today.

Caroline Bond Day was born in Montgomery, Alabama in 1889. Her widowed mother was determined that her daughter receive a good education and moved the family a number of times in pursuit of this. Eventually, Caroline went on to earn her first bachelor’s degree in 1912 from an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities): Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), where one of her mentors was W.E.B. Du Bois.

Eventually, Caroline went on to earn her first bachelor’s degree in 1912 from an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities): Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), where one of her mentors was W.E.B. Du Bois.

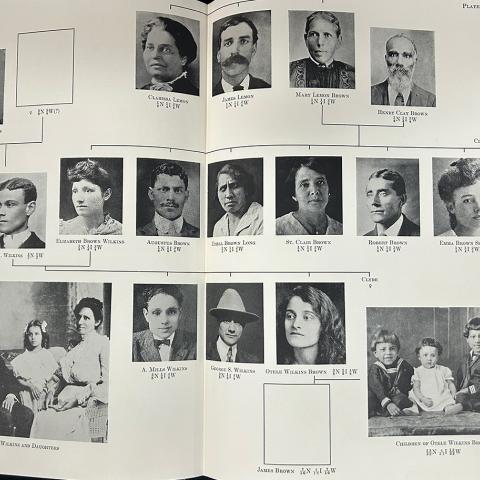

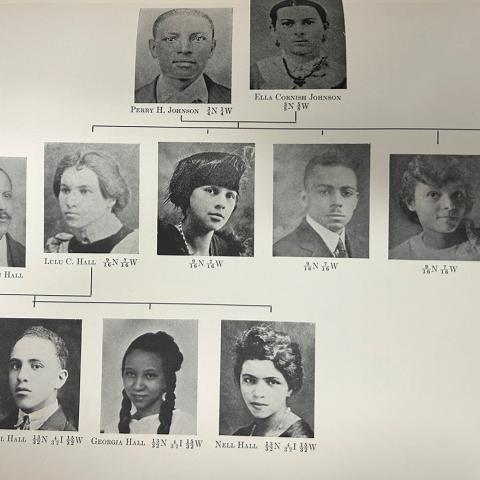

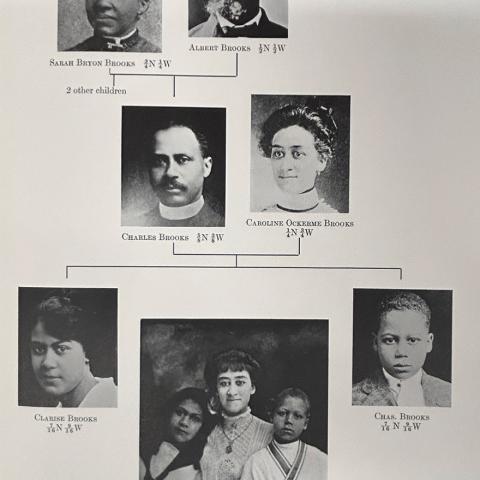

Ms. Day entered Radcliffe in Boston, Massachusetts in 1916. Radcliffe refused to recognize her bachelor’s degree as Atlanta University, like many Black institutions at that time, was denied accreditation. Radcliffe also denied Black students on-campus housing and Caroline commuted from lodgings 5 miles away in South Boston. In her second year, she began a study of mixed-race families, which reflected her own. She graduated with her second bachelor’s degree in 1919, but her study remained incomplete due to a lack of funding. After graduation, Ms. Day worked as a college instructor and married; in 1927 she secured funding and returned to her anthropological work at Radcliffe, recruiting thousands of individuals from hundreds of multiracial families, including her own. Her thesis was published in 1932 and challenged the racism that prevailed in science and higher education at that time, demonstrating that race is not a fixed category and that there is no scientific basis to the claim that whites as a group are superior to any other group.

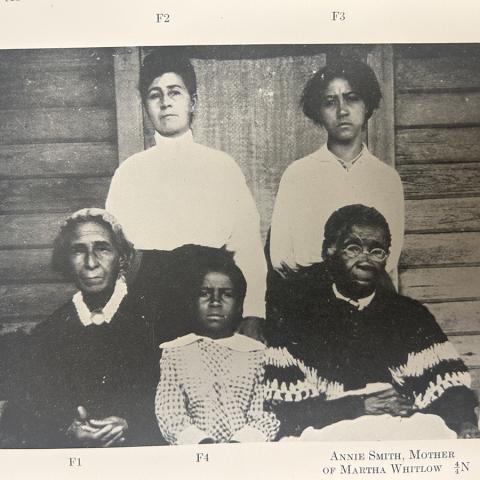

In A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, Ms. Day explains the reasoning behind her study and that she divided the individuals taking part into two distinct groups – one for older individuals who experienced life under enslavement and another group who were  “principally the children and grandchildren of freedmen.” This is because those who lived under enslavement - by the very nature of that institution - were deprived of education and other opportunities. Ms. Day also addressed the widespread sociopolitical and cultural impact of someone being from a “mixed” family and thus experiencing the economic and other benefits, however limited, that come with having a white parent. She also disputed the idea that those with “mixed” family lines are inherently better than those coming from “full-blooded” Black families. In challenging the prevailing beliefs of that time, Ms. Day used the same instruments of anthropology that had long been used to perpetuate scientific racism and prop up eugenics.

“principally the children and grandchildren of freedmen.” This is because those who lived under enslavement - by the very nature of that institution - were deprived of education and other opportunities. Ms. Day also addressed the widespread sociopolitical and cultural impact of someone being from a “mixed” family and thus experiencing the economic and other benefits, however limited, that come with having a white parent. She also disputed the idea that those with “mixed” family lines are inherently better than those coming from “full-blooded” Black families. In challenging the prevailing beliefs of that time, Ms. Day used the same instruments of anthropology that had long been used to perpetuate scientific racism and prop up eugenics.

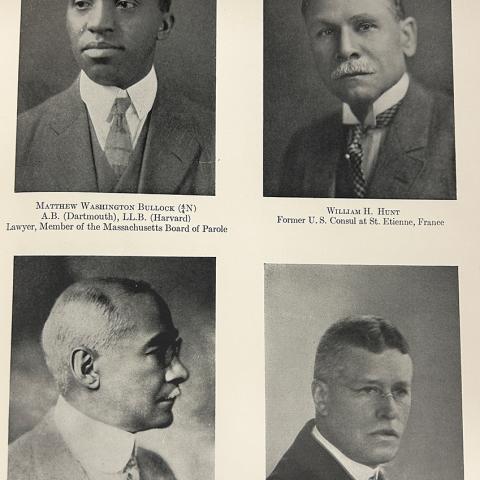

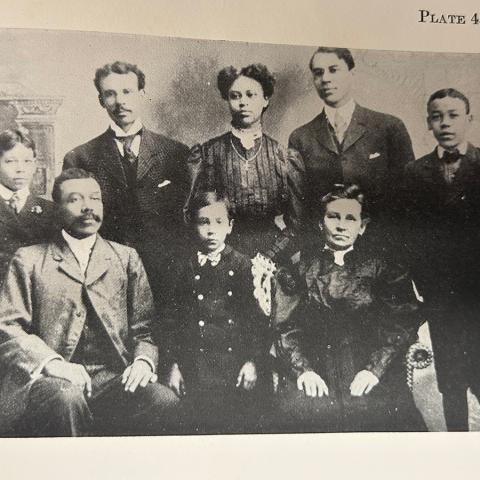

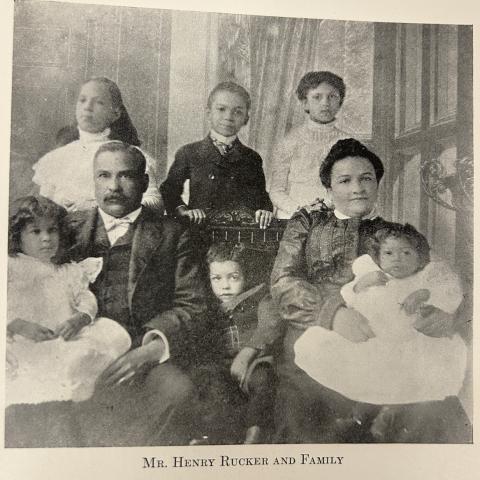

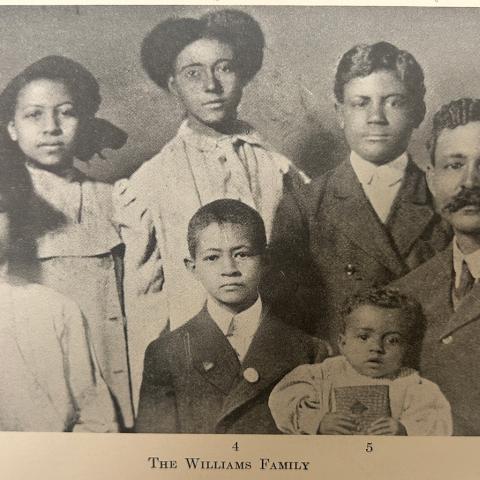

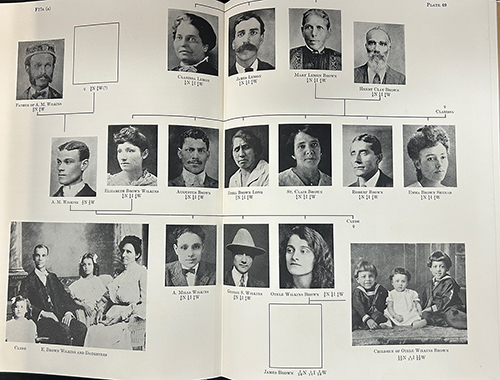

Caroline Bond Day used her own background and experiences to build trust with the families and individuals that became a part of her study. She interviewed them, took photographs and hair samples, created family trees, and performed the analysis. Although her name is not well known, she was a trail blazer in her field and contributed to the end of eugenics and scientific racism that was prevalent in anthropology as well as in so many other fields in higher education. While CSUN’s Special Collections & Archives holds Ms. Day’s thesis, her archives are found at the Harvard Peabody Museum.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: special collections, publications, united states

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries