A Septennial Review: Criticism and Praise in the Reginald Smith Brindle Collection

by Alex Turney, graduate student of Steve Tkachuk and IGRA fellow for the 2025-26 academic year - December 09, 2025

Seven years ago, the International Guitar Research Archives (IGRA) at CSUN opened the Reginald Smith Brindle Collection to the public. At the time, former IGRA student assistant Brenton Contreras wrote a post celebrating the new collection and highlighting aspects of Smith Brindle’s life and career. All these years later, the collection still provides fascinating insights into the composer and the world he lived in.

Brenton’s blog post touched on one area of particular interest to classical guitar students: proof that Andres Segovia liked Smith Brindle’s music. As Brenton explains, we know about Segovia’s affection for the music through correspondences between Segovia and Smith Brindle archived in the collection. This relationship helps fortify Smith Brindle’s reputation as a credible and prolific guitar composer, but he also composed a large number of pieces for other solo instruments, chamber ensembles, and orchestral settings.

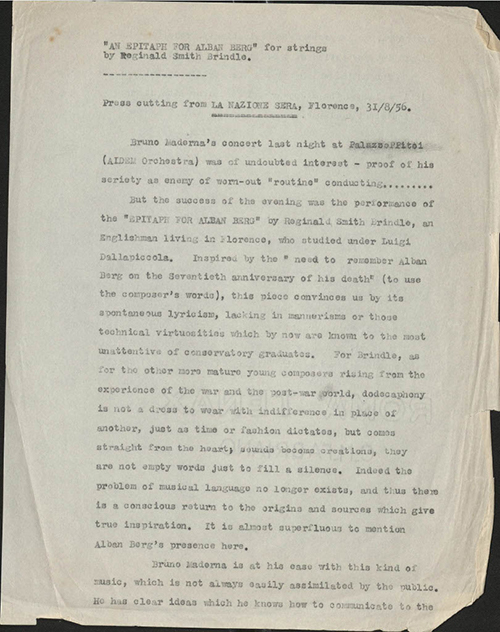

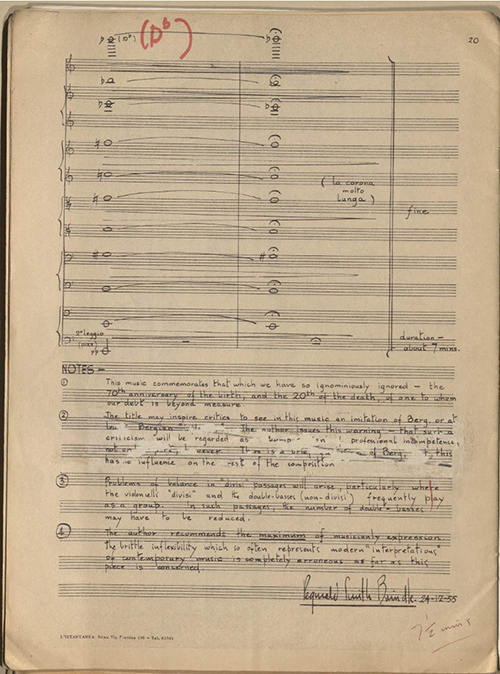

Another area of the Smith Brindle Collection that sheds some light on the composer’s music outside of the guitar is Series III, which contains a folder full of press cuttings in several languages covering public performances of Smith Brindle’s work. As with any artist, some reviews applaud the composer, some criticize him, and some are downright indifferent.  Regardless of tone, the reviews reveal interesting details about music consumption, public perception of avant-garde movements, and the differing values critics of the time held.

Regardless of tone, the reviews reveal interesting details about music consumption, public perception of avant-garde movements, and the differing values critics of the time held.

A favorite review comes from a translated press cutting of La Nazione Sera in Florence. The author is unknown, but their comments challenge assumptions about the intellectualism of avant-garde music. In glowing terms, they praise Smith Brindle’s use of serialism as a tool of emotional expression: "For Brindle, as for the other more mature young composers rising from the experience of the war and the post-war world, dodecaphony is not a dross to wear with indifference in place of another, just as time or fashion dictates, but comes straight from the heart; sounds become creations, they are not empty words just to fill a silence." Personally, I’ve had trouble relating to serialist or atonal music, but that trouble has been challenged by the clarity this reviewer had about the relationship of serialism to emotional expression.

Then again, my personal trouble relating to serialism might not be so personal. Another reviewer—writing in The Times on February 8, 1957 about a performance Smith Brindle’s suites for violin and piano—was unimpressed. The critic groans about Smith Brindle’s “dodecaphonic methods,” his involvement in “that kind of workshop,” and offers only a narrow and backhanded compliment-that the piece has “the virtue of knowing when to stop.”

Then again, my personal trouble relating to serialism might not be so personal. Another reviewer—writing in The Times on February 8, 1957 about a performance Smith Brindle’s suites for violin and piano—was unimpressed. The critic groans about Smith Brindle’s “dodecaphonic methods,” his involvement in “that kind of workshop,” and offers only a narrow and backhanded compliment-that the piece has “the virtue of knowing when to stop.”

Other critics were glad that Smith Brindle continued exploring new sounds, however. A. F. Leighton’s review celebrates him as an innovator, reporting that “the two improvisations for piano are possibly the first of their kind: improvisations in serial technique.” Often assumed to be measured, planned, and exact, serialist techniques, according to this critic, were pushed beyond expectations by Smith Brindle. “What matters most,” Leighton writes, is “that we have in our midst composers willing and able to employ techniques which are enjoying currency elsewhere.”

In yet another twist, one more critic argues that Smith Brindle’s music would be better served if he were less vocal about his innovations and instead let the music speak for itself. Daily Telegraph critic Donald Mitchell, writing about the debut of Smith Brindle’s orchestral work Cosmos, laments that “perhaps if we had not been made quite so incessantly aware of the nature of the composer’s preoccupations, his scoring might have struck one as agreeably colorful.” In the end, though, Mitchell finds Smith Brindle’s experiments lacking, concluding that “Mr. Brindle’s tinkering about with fashionable percussion noises scarcely seems to meet the challenge of his self-confessed programme.”

To avoid casting Smith Brindle’s orchestral works in a negative light before the end of this post, I’ll share one last review. A page from the August 13, 1964 issue of The Listener titled "Music: Full Circle" counters the last critique. Writing about the positive recognition of Smith Brindle’s "Creation Epic," the author acknowledges his control as a composer. As the piece begins with “redoubtable virulence, full of cataclysms, menace, unease, and convulsive stridency,” the author appreciates Smith Brindle’s ability to come back to the center, noting that the "tension eases up…suggest[ing] that a degree of normality is in the offing.” As a result of this flexibility, the anonymous critic reports that the performance was “vociferously applauded.”

So, whether you consider Reginald Smith Brindle a daring serialist innovator, a beloved and nimble—if sometimes ineffective—orchestral experimentalist, or simply as one drop in the wave of music in the late 20th century, the reviews of his work in the collection have a great deal to say. As distance grows between our time and the past, looking over past reviews can be a reminder that people in every era have held radically different opinions.

Image Gallery

Post tagged as: igra, archives, international

Read more Peek in the Stacks blog entries