by Keith Rice, Ph.D., Historian/Archivist, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center

By the turn of the twentieth century the Central Avenue District was on its way to becoming the center of African American life in Los Angeles. It was a slow process that took several decades to complete. Several factors contributed to that development.  The Central Avenue District was constructed by surrounding white neighborhoods that barred minorities from living in them. Located on the Eastside of the city, the Central Avenue District was bounded by two north-south streets, San Pedro on the west and Alameda on the east. The white neighborhoods created a buffer for wealthy whites living on the west side of town. In 1910 the district’s southern boundary was in downtown at Washington Boulevard but by 1920 it had moved south to Jefferson Boulevard. By the 1940s, the center of the Central Avenue district had moved further south to 41st and Central. Its southern border had extended to the next white neighborhood at Slauson Avenue, before turning Black again at 92nd street in Watts.

The Central Avenue District was constructed by surrounding white neighborhoods that barred minorities from living in them. Located on the Eastside of the city, the Central Avenue District was bounded by two north-south streets, San Pedro on the west and Alameda on the east. The white neighborhoods created a buffer for wealthy whites living on the west side of town. In 1910 the district’s southern boundary was in downtown at Washington Boulevard but by 1920 it had moved south to Jefferson Boulevard. By the 1940s, the center of the Central Avenue district had moved further south to 41st and Central. Its southern border had extended to the next white neighborhood at Slauson Avenue, before turning Black again at 92nd street in Watts.

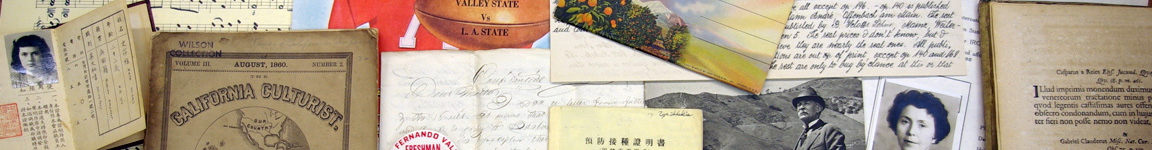

The Bradley Center has one of the most extensive collections of photographs documenting the Black experience in Los Angeles. While places like Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Malibu have been associated with the California Dream, the Central Avenue corridor was not. But it was one of the few places that African Americans could call home while seeking the California Dream during the first sixty years of the twentieth century. Its community members commonly referred to it as the Eastside. It has also been dubbed South Central, which the media has been known to associate with poverty and violence. But the archived images taken by the photographers, who lived there, show a Black community that flourished in spite of the limitations placed on it through housing discrimination and racism.

The images presented here are examples of the jazz-like innovation and improvisation that the descendants of enslaved Africans have used to create something out of nothing in the Americas for hundreds of years. These images capture businesses in the Central Avenue District that were often overlooked or unavailable to African Americans by mainstream institutions. For instance, mainstream newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner did not focus on news in communities of color. To fill that void the African American publishers Charlotta Bass (The California Eagle) and Leon Washington (Los Angeles Sentinel) reported on the news that was occurring in their community.

Another popular business industry that could be found on Central Avenue was entertainment. Between the 1920s and 1950s the nightclubs in the Central Avenue District hosted some of the most talented Black entertainers. It was referred to as the “West Coast Harlem.” The peak of the Central Avenue District occurred in the 1940s during World War II when thousands of African Americans migrated to the area from the south to work in the defense industry. Clubs such as Club Alabam and Jack’s Basket Room were anchored by the Dunbar Hotel (formerly the Somerville Hotel). The Dunbar was built by the first Black graduates of the University of Southern California Dental School Drs., John and Vada Somerville. In addition to the nightclubs Leon Heflin Sr. put on the Cavalcade of Jazz at Wrigley Field every summer from 1945 until 1958.

Another popular business industry that could be found on Central Avenue was entertainment. Between the 1920s and 1950s the nightclubs in the Central Avenue District hosted some of the most talented Black entertainers. It was referred to as the “West Coast Harlem.” The peak of the Central Avenue District occurred in the 1940s during World War II when thousands of African Americans migrated to the area from the south to work in the defense industry. Clubs such as Club Alabam and Jack’s Basket Room were anchored by the Dunbar Hotel (formerly the Somerville Hotel). The Dunbar was built by the first Black graduates of the University of Southern California Dental School Drs., John and Vada Somerville. In addition to the nightclubs Leon Heflin Sr. put on the Cavalcade of Jazz at Wrigley Field every summer from 1945 until 1958.

The Central Avenue District remained home for many Black families well into the 1960s and 1970s. However, with the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 barriers to Black home ownership outside of the Central Avenue District were removed, at least legally. With the easing of those restrictions Black people started to venture outside of the Central Avenue District in search of newer housing stock on the West Side and in the suburbs. The construction of the north-south 110 freeway and east-west 10 freeway cut right through the heart of the Central Avenue District and contributed to the westward exodus away from Central Avenue. An unexplainable phenomenon that appears to be particular to Los Angeles is that for the last 70 years or so, as Black people migrated further west so did the demarcation line for the West Side. Presently most people consider west of the 405 Freeway as the west side of Los Angeles.