by Philip W. Walsh, Ph.D., Lecturer, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies and Liberal Studies

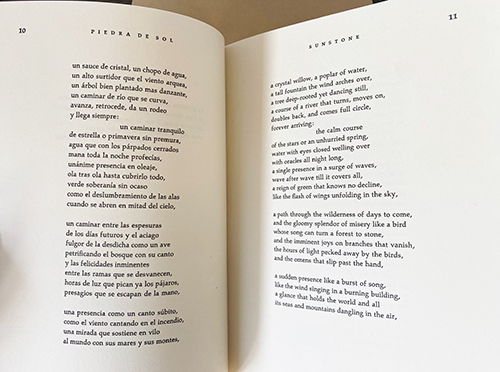

Octavio Paz (Mexico City, Mexico, 1914-1998) was a poet, essayist, diplomat, and editor. He served in Mexico's diplomatic corps until 1968, when he resigned in protest of the massacre of student protesters by the Mexican Armed Forces in 1968. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990; his most notable works are his book length essay El laberinto de soledad [The Labyrinth of Soledad] (1950) and his poem Piedra de sol (1957), translated into English as Sunstone by Eliot Weinberger in 1991. Like much of Paz’s work, Piedra de sol is self-referential, exploring the space between desire and fulfilment, the world and the poet's struggle to represent the world.

of the massacre of student protesters by the Mexican Armed Forces in 1968. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990; his most notable works are his book length essay El laberinto de soledad [The Labyrinth of Soledad] (1950) and his poem Piedra de sol (1957), translated into English as Sunstone by Eliot Weinberger in 1991. Like much of Paz’s work, Piedra de sol is self-referential, exploring the space between desire and fulfilment, the world and the poet's struggle to represent the world.

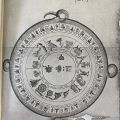

The poem's title refers to the Aztec calendar discovered in Mexico City in 1790; the calendar had been buried by its creators to prevent its destruction by the Spanish. The artifact documents the history of the four previous ages which came before the year it was carved, recording the destruction of the majority of the human race each time—implying, as well, their rebirth. Paz's poem interprets this destruction and rebirth to mean that time and history are circular rather than linear, as they tend to be in Western thought. This sense of history, native to Aztec thought, was a response to recent history in Europe, particularly the destruction born out of World War II, from which Europe was still recovering, and the fascism of Franco's Spain.

The text, which ends with the same six and a half lines with which it begins, also reflects the circular time of Aztec cosmology. The 584 lines of the poem reflect the number of days it takes the planet Venus to orbit the sun, Venus being the planet associated with the Quetzalcóatl, the Aztec creator of the human race.

Paz’s poem not only reflects the indigenous peoples of Mexico, but also the influence of surrealism, which Paz encountered while he was in Paris as cultural attaché for Mexico, from 1945 to 1951. Paz befriended André Breton and other surrealists, contributed to surrealist journals, and participated in their exhibitions. This poem is a reflection of Paz's belief, derived from the Surrealists, that the important struggles are not economic, but rather spiritual, and that “the great conquest is not of outer but of inner space.”

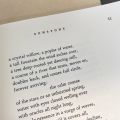

Sunstone shows the influences of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, but Paz does not give in to despair, as Eliot does in his poem. Paz instead focuses on the natural world as an antidote to the horrors of modern society. The reader finds nature imagery throughout his poem—willows and poplars, rivers, tree lined arcades, a peach (perhaps an allusion to the peach mentioned by the narrator of Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock). These local natural phenomena are set alongside longer natural cycles, such as “the calm course of the stars or the unhurried spring”—the night sky and the seasons offer respite from horrors such as the bombing of Madrid by fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War (Paz was in Spain when this bombing took place, and witnessed the devastation it created). The poet here reminds the reader that there is a larger order underlying the chaos created by events in human history.

Sunstone shows the influences of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land, but Paz does not give in to despair, as Eliot does in his poem. Paz instead focuses on the natural world as an antidote to the horrors of modern society. The reader finds nature imagery throughout his poem—willows and poplars, rivers, tree lined arcades, a peach (perhaps an allusion to the peach mentioned by the narrator of Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock). These local natural phenomena are set alongside longer natural cycles, such as “the calm course of the stars or the unhurried spring”—the night sky and the seasons offer respite from horrors such as the bombing of Madrid by fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War (Paz was in Spain when this bombing took place, and witnessed the devastation it created). The poet here reminds the reader that there is a larger order underlying the chaos created by events in human history.

This edition features illustrations from historian Mariano Fernández de Echeverría y Veytia's Los calendarios mexicanos [The Mexican Calendars], completed in 1782, but not published until 1836. There have been at least four previous translations of this poem into English; our edition has the original Spanish and the English translation on facing pages.