Some Peek in the Stacks blog posts are authored by CSUN students who work in Special Collections and Archives. This week's post was written by Brenton Contreras, a student assistant in the International Guitar Research Archives (IGRA). Brenton is an undergraduate majoring in Guitar Performance.

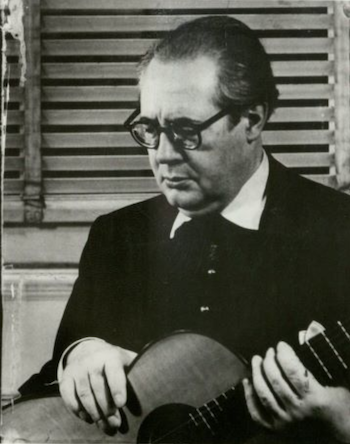

"To anticipate the exact progress into the future is impossible. If I could produce any example of what the future holds in store, it would no longer be of the future, but of the present." This is the opening line from the English composer Reginald Smith Brindle's essay on music entitled Music in The Modern Age-And After. Smith Brindle who lived from 1917-2003 is best known for his compositions for the guitar, but he also composed for a variety of other instruments. He was an advocate and supporter of modern music which swept throughout the world in the second half of the twentieth century. This music was characterized by a shift away from traditional formal structures of music to more abstract forms and styles, which also coincided with many other mediums of art during that time.

"To anticipate the exact progress into the future is impossible. If I could produce any example of what the future holds in store, it would no longer be of the future, but of the present." This is the opening line from the English composer Reginald Smith Brindle's essay on music entitled Music in The Modern Age-And After. Smith Brindle who lived from 1917-2003 is best known for his compositions for the guitar, but he also composed for a variety of other instruments. He was an advocate and supporter of modern music which swept throughout the world in the second half of the twentieth century. This music was characterized by a shift away from traditional formal structures of music to more abstract forms and styles, which also coincided with many other mediums of art during that time.

In February 2018 The Reginald Smith Brindle Collection was made available within the International Guitar Research Archives at CSUN. This amazing addition to the IGRA collection was acquired in 2014 and chronicles many aspects of Smith Brindle's life such as correspondences, music and presentations. Smith Brindle began his musical endeavors as a kid playing Jazz with friends. Smith Brindle says that he was primarily a saxophonists, but he enjoyed playing numerous other instruments as well. During this time period he even won a few band competitions on the clarinet. Around the time he was 20, Smith Brindle discovered classical music and absolutely fell in love with it. He ultimately became obsessed with the beauty of classical structures within music. After extensive studying and training Smith Brindle decided he wanted to become a church organist. All of the formal rules he learned would eventually be broken by him later on in life within his compositions.

Even with his utter love for the organ Smith Brindle was still a great fan of many other instruments, especially the guitar. During the Second World War Smith Brindle was stationed in numerous locations away from a piano and being an organist made it impossible to travel with an instrument, so he did what any sensible person would do. On his travels he brought along with him a guitar that acted as his own personal orchestra and allowed him to continue his love of composing and playing music. At this point in time Smith Brindle was a fairly confident organist. Though his skills on the guitar were quite lacking, he did not allow that to stop him. Determined, Smith Brindle decided to begin the difficult task of teaching himself this very challenging instrument while in conflict zones. In doing so he gained a deep understanding of the guitar and in time learned how to write compelling music for the instrument. In his own words "I knew nothing of the classical guitar repertoire at all. Not a note. So I had to make up my own music. Perhaps this was a good thing. Perhaps this was the real way to discover what the guitar can really do."

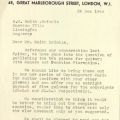

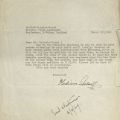

During his entire time in the service Smith Brindle honed his skill not only at the guitar, but also at composition and once the war ended he began the process of sending his guitar music to publishers in an attempt to get it published. This was unfortunately a very slow and painful process as the classical guitar was not held in high regard as other instruments are. In some ways this is unfortunately still true to this day. Though at this time there were a handful of true classical guitar masters playing and recording music their notoriety was mainly confined to the people who loved the classical guitar and the music written for it. During this time period Smith Brindle was within a modern compositional renaissance and was trying desperately to get any of his works published. Due to the stature of the classical guitar many publishers opted not to publish them, believing music for the guitar would never sell. Some publishers did take his music seriously and did see value in it, but they were unfortunately unable to offer him any significant amount of money. Smith Brindle was in many cases forced to let his music go for next to no compensation. On top of that in some instances he would not even receive royalties for the music that he worked tirelessly on. This was one of the harder times in Smith Brindle's life, but nonetheless he persisted and eventually garnered attention from some of the best classical guitarists around.

During his entire time in the service Smith Brindle honed his skill not only at the guitar, but also at composition and once the war ended he began the process of sending his guitar music to publishers in an attempt to get it published. This was unfortunately a very slow and painful process as the classical guitar was not held in high regard as other instruments are. In some ways this is unfortunately still true to this day. Though at this time there were a handful of true classical guitar masters playing and recording music their notoriety was mainly confined to the people who loved the classical guitar and the music written for it. During this time period Smith Brindle was within a modern compositional renaissance and was trying desperately to get any of his works published. Due to the stature of the classical guitar many publishers opted not to publish them, believing music for the guitar would never sell. Some publishers did take his music seriously and did see value in it, but they were unfortunately unable to offer him any significant amount of money. Smith Brindle was in many cases forced to let his music go for next to no compensation. On top of that in some instances he would not even receive royalties for the music that he worked tirelessly on. This was one of the harder times in Smith Brindle's life, but nonetheless he persisted and eventually garnered attention from some of the best classical guitarists around.

Guitarists like Andres Segovia and Julian Bream became very fond of Smith Brindle's music and developed relationships with him through letters they exchanged with one another. As their friendship grew Smith Brindle decided to write music and dedicate it both of these two highly esteemed classical guitarists. In one letter that was sent by Andres Segovia, he writes to Smith Brindle describing his love for the music that was sent to him:

I am very sorry that I received your letters and musics only now, at the end of my tour in the United States… it is easy to see that you are a musician of delicate taste and well trained technique. There are not many good composers for the guitar and we must, all guitarists, welcome a young talent like your's [sic].

It was recognition from people like Andres Segovia and Julian Bream that made all of Smith Brindle's painstakingly hard work justified. For a young composer to get such a genuine and heartfelt letter from a great master was such a humbling and rewarding experience. This helped to reinforce Smith Brindle's steadfast dedication to continue to keep writing more music for this instrument that he loved. The guitar held a deep connection to his soul, stemming from his days traveling with an instrument during World War II. Even with limited financial rewards, Smith Brindle did not stop composing for the guitar. After achieving notoriety from these prominent guitarists Smith Brindle now knew that his music was not worthless and it most certainly could sell to a larger audience. Thankfully this mindset overtook Smith Brindle because throughout the rest of his life his music became some of the most interesting contemporary classical music being written. The modern compositional techniques he used helped to push classical music into the future and we are all now culturally richer because of his music and his impact on classical music overall.

I hope that many of you take the opportunity to peer into Smith Brindle's life through this collection in Special Collections & Archives. Smith Brindle was and is still an interesting and engaging person to read about. I will leave you all with one more short line from Smith Brindle's Music In The Atomic Age-And After "Music will change into infinite forms, never going back, but always forward… Music is as infinite as space, it will go on, 'worlds without end.'" Unless otherwise noted, images in the gallery below are from the Reginald Smith Brindle Collection.