During the Spring 2023 semester, Special Collections & Archives collaborated with Dr. Colleen Tripp's English 630, "Modern Monsters: Then & Now." Students in the class selected items from our collections of pulps, comics, and horror stories, then authored a series of blog posts in which they examined visual and other representations of the monstrous in the texts they chose. This is the eigth and final post of the series.

Pulp magazines, or “the pulps” as they are colloquially known are older than what popular culture remembers of them. Starting as early as 1896 pulps like The Argosy had already begun publication and were starting to accrue an audience.1 It wasn’t until the 1920s and 1930s that these magazines adopted both their fame and infamy. Originally used as a pejorative term, the pulps—along with “the slicks”—were reviled by some in the publishing industry as a sign of literary decline.2 Despite this contentiousness, pulp magazines began to flourish, and among its biggest giants was the New York City-based publisher Street & Smith.

In 1933, Street & Smith acquired Astounding Stories, one of the first pulp magazines to center the genre of  science-fiction as its twenty-cent selling point.3 In the following years “John W. Campbell would join the editorial staff of Astounding Stories in September 1937, replacing F. Orlin Tremaine as editor in 1938 when Tremaine became editorial director at Street and Smith.”4 In 1939 Campbell would usher in a “companion fantasy magazine, Unknown”5 alongside Astounding Stories. Though only lasting from 1939-1943, Unknown was extensively influential in the fantasy and science fiction genre and is credited as the progenitor of the urban fantasy subgenre.6

science-fiction as its twenty-cent selling point.3 In the following years “John W. Campbell would join the editorial staff of Astounding Stories in September 1937, replacing F. Orlin Tremaine as editor in 1938 when Tremaine became editorial director at Street and Smith.”4 In 1939 Campbell would usher in a “companion fantasy magazine, Unknown”5 alongside Astounding Stories. Though only lasting from 1939-1943, Unknown was extensively influential in the fantasy and science fiction genre and is credited as the progenitor of the urban fantasy subgenre.6

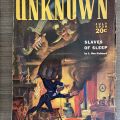

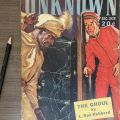

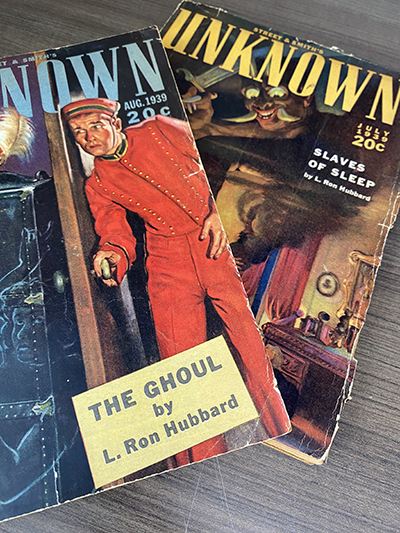

During its run, Unknown featured a variety of prominent writers, some of whom became staples of the short-lived magazine. Perhaps the most famous of these writers was L. Ron Hubbard—the future founder of Scientology. Before founding the controversial religious foundation, Hubbard was a known author and writer, often dabbling in the science fiction and fantasy genres. In 1939, the first year of Unknown’s publication, the American author’s name graced the cover pages of the magazine’s July and August issues, prominently featuring his story as a main selling point for the prospective reader.7

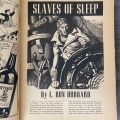

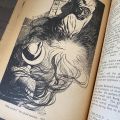

The illustrations provided for both the July and August 1939 issues of the magazine depict scenes from the major story of each issue, Hubbard’s “Slaves of Sleep” and “The Ghoul” respectively. In both illustrations there is a depiction of a white man—or men—being assailed by some malevolent entity; in “Slaves of Sleep” this entity is in the form of an Eastern-inspired demon8, and in “The Ghoul” it is in the form of a vaguely Eastern inspired man.9 The use of Eastern-inspired imagery is a marker for the orientalism that ran rampant through many texts of the time as it offered an alienating other to the otherwise Western sensibilities of its readers. Whereas readers had become accustomed to the haunts of Europe and fantastical imaginations of the Wild West, the focus on Orientalism created a divide of an “us” versus “them” narrative wherein Eastern cultures, religions, and even peoples are othered into the realm of the monstrous by Western society.10

The monstrousness of the “Orient” is further compounded by Western notions of the Gothic. In “Slaves of Sleep” although the demon—Ifrit—is undeniably mythological in origin, the way he is portrayed within the illustrations plays on Western fears; the demon’s complexion is dark and his face ugly—he wields a sword of Eastern design with his claw-like hands. Likewise, the eponymous ghoul is depicted as a vaguely Eastern man draped in off-white robes, sporting a headdress or turban of indeterminate origin or culture. This villain is hidden from the view of the white protagonist, armed with a weapon and ready to strike as an ugly expression adorns his face. In both images the gothic works as a “rhetorical style and narrative structure designed to produce fear and desire within the reader.”11 The otherness of the “Orient” therefore becomes both a repulsion and a delight as its attraction is the allure of fear and, quite literally, the unknown.

The narrative structure of these two works also points to the use of Eastern-inspired horror to excite the readers’ senses. In “Slaves of Sleep” the protagonist Jan Palmer finds himself in a new body in another dimension, a realm ruled by Ifrit and his monstrous disciples. The reader is at once welcomed to a fantastical land while also fearful of its conception. The idea of a whole realm, a whole ruled by this monstrous other serve as the driving horror within this tale.12 Conversely, in “The Ghoul” the monstrous ghoul manifests within the human realm of Western society—New York. A young hotel worker, Irish, interacts with a presumably empty trunk of the guest from room 1312. While there doesn’t appear to be any material thing within the trunk, Irish starts to hear voices and comes under suspicion by the turban-wearing man. Throughout the story Irish is tormented by his meddling as the guest hounds him about his actions and the voice he hears starts to invade his everyday life.13 The horror here is, once again, the unknown horrors of other cultures and peoples, and the idea of knowledge best left alone.

1. “Biographical Database.” Pulpmags, 27 Apr. 2023,

https://www.pulpmags.org/contexts/essays/golden-age-of-pulps.html

2. R. D. Mullen. “From Standard Magazines to Pulps and Big Slicks: A Note on the History of US General and Fiction Magazines.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, 1995, pp. 144–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4240420. Accessed 19 Apr. 2023.:144

3. “Biographical Database.” Pulpmags

4. Page, Michael R. “Astounding Stories: John W. Campbell and the Golden Age, 1938–1950.” The Cambridge History of Science Fiction, edited by Gerry Canavan and Eric Carl Link, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019, pp. 149–165: 149

5. Mullen, “From Standard Magazines to Pulps and Big Slicks: A Note on the History of US General and Fiction Magazines,” 157

6. Mullen, 157

7. Mullen, 157

8. Hubbard, L. Ron. “Slaves of Sleep.” Unknown, Vol. 1, no. 5, July 1939, pp. 9-78.

9. Hubbard, L. Ron. “The Ghoul.” Unknown, Vol. 1, no. 6, Aug. 1939, pp. 9-74.

10. Said, Edward. “‘INTRODUCTION,’ FROM ORIENTALISM.” Classic Readings on Monster Theory: Demonstrare, Volume One, edited by Asa Simon Mittman and Marcus Hensel, Arc Humanities Press, 2018, pp. 57–66. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvfxvc3p.11. Accessed 28 Apr. 2023.: 57

11. Halberstam, J. “‘PARASITES AND PERVERTS: AN INTRODUCTION TO GOTHIC MONSTROSITY,’ FROM SKIN SHOWS: GOTHIC HORROR AND THE TECHNOLOGY OF MONSTERS.” Classic Readings on Monster Theory: Demonstrare, Volume One, edited by Asa Simon Mittman and Marcus Hensel, Arc Humanities Press, 2018, pp. 75–88. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvfxvc3p.13. Accessed 28 Apr. 2023: 76

12. Hubbard, “Slaves of Sleep,” 54

13. Hubbard, “The Ghoul,” 15